Bonds & Interest Rates

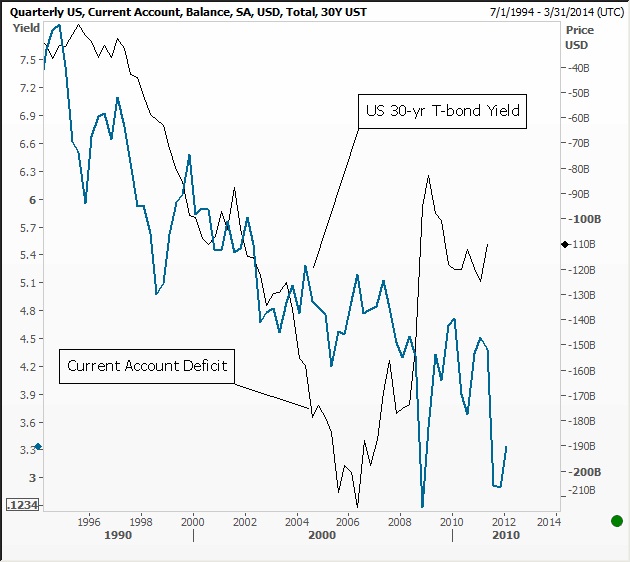

Watching the rise in US long-bond yields got me to wondering: What if the fall in the Japanese and Chinese current account surpluses continues, i.e. this trend is for real?

US Current Account Deficit (black) vs. 30-yr US Treasury Bond Yield (blue):

If so, it means both countries recycle less of their yen and yuan, respectively, back into the US capital markets. It means the global economy could finally see some rebalancing between the major deficit country, the US and surplus country, China. It means the US current account deficit, which seems to worry many people and economists alike, is likely to improve, as Japan and China morph increasingly into capital importers instead of capital exporters.

Has this rebalancing begun? We don’t know yet. But interestingly, given the needs for Japan to rebuild and China to change its growth model, it could very much be the next major global macro trend for the global economy. If so, there are three major implications, and several investment themes spawned:

Has this rebalancing begun? We don’t know yet. But interestingly, given the needs for Japan to rebuild and China to change its growth model, it could very much be the next major global macro trend for the global economy. If so, there are three major implications, and several investment themes spawned:

1) US long bond yields have likely bottomed (price topped), and

2) The next major growth phase for the global economy will be the rise of the Asian Consumer.

3) Global capital and trade flow will become a two-way street.

Some additional comments:

-

Japan may be morphing into a capital importer (first year-on-year trade deficit since 1980 was recorded in 2011). Interestingly, the tsunami and its devastation may have been the catalyst that leads to a normalization of the Japanese economy, i.e. rising interest rates, local commercial bank lending, and local business investment.

— Because of Japanese nuclear power going offline, Japanese imports of crude oil is up 350% compared to the same month last year.

— Normalization is part and parcel to a weaker yen as the game of risk aversion and “hiding” large pools of capital goes away.

-

China’s GDP growth will likely continue to fall (inherently reducing its giant reserve surplus), but this will not likely be a disaster if China’s growth model changesto support consumers (enriched consumers don’t care about GDP numbers; they care about reality) and moves away from State Owned Enterprises, which includes massive capital investment projects and consistent export subsidies of companies operating in the red or on wafer thin margins.

— No need to recycle surpluses and keep buying US Treasuries in order to keep the currency suppressed, because …

— A stronger yuan will increase consumer wealth, relatively, making the transition to a new model more efficient, i.e. benefiting import industries at the expense of exporters.

-

Asian-block countries will be relieved if China signals it is serious about making a transition that empowers its consumers. Asian-block nations who have implicitly and explicitly suppressed the value of their own currencies over the last several years thanks to China’s explicit currency suppression and growth model. Asian-block countries compete against China for the same Western demand. Thus, in the process of that competition, consumer market development across Asia as a whole has been stymied. Thus, China’s signaling of a change in its local growth model will likely be reinforced strongly across the region.

-

Stronger Asian consumer demand and stronger Asian currencies mean Western consumer goods flow more freely to the East and the US trade balance improves dramatically, and it will be quite good for Europe too. Thus, the US trade balance and need for external capital to close the current account gap will decline naturally as Asian consumer demand increases.

Risks to this rosy long-term scenario are many; here are just a few examples:

-

Contagion to emerging markets triggered by the European debt crisis could be severe …

-

Potential financial crisis in China as debt grows to dangerous proportions and unrest is met with more internal crackdowns on its citizens …

-

A major debt crisis in Japan, triggered by its need to import funds, but inability to see long-term interest rates rise (which is part and parcel to attracting funds from international investors) …

-

US remains mired in its seemingly “never-ending” war policy and do little to improve its unsustainable fiscal deficits …

Net-net if this major trend plays out, it means the US may avoid its fiscal train-wreck destiny and paradoxically if Chinese leaders trust their average citizens more, they will gain even more control of their own destiny.

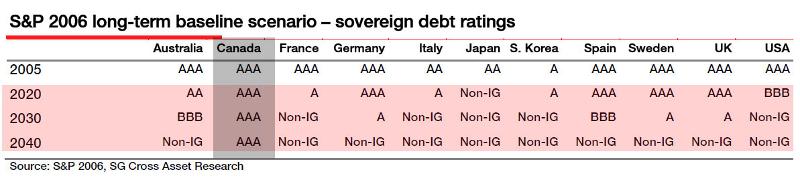

According to research by SocGen, by 2040 Canada will be the only G7 country with investment grade sovereign debt. By as early as 2030 the US, France, Italy and Japan will all lose investment grade status. To put this into perspective this means that in less than 2 decades the debt of countries currently representing approximately 50% of global GDP will be ineligible for investment by the smallest municipal pension fund.

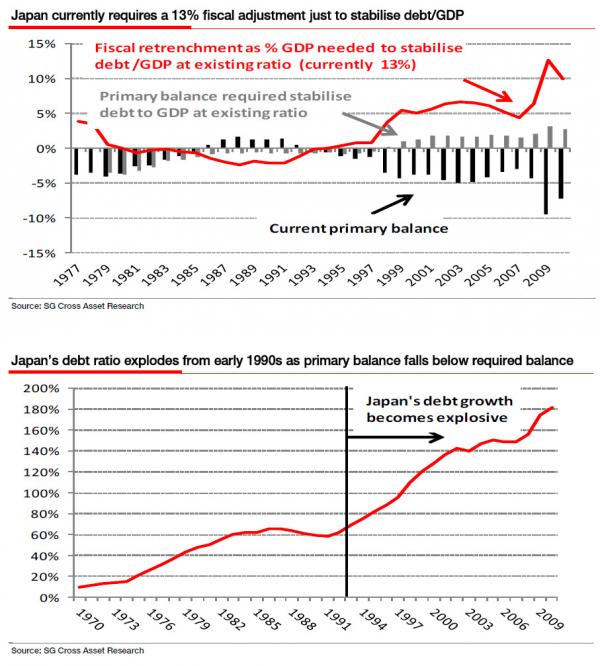

Japan is actually expected to lose investment grade status in less than 10 years and looking at the charts below this should not come as a surprise when it happens. BTW – Japan by itself represents almost 10% of global GDP.

Clearly some profound changes are coming to the sovereign debt markets and most importantly to the idea of the “risk free” rates of return that can be found there. As one wag recently described it, sovereign debt no longer represents “risk free return” but rather “return free risk”.

US Budget Deficits – Sustainable?

Perhaps a picture truly is worth a thousand words. In this case think of the word “unsustainable” over and over again.

If Greece is Bad What are the UK and Japan?

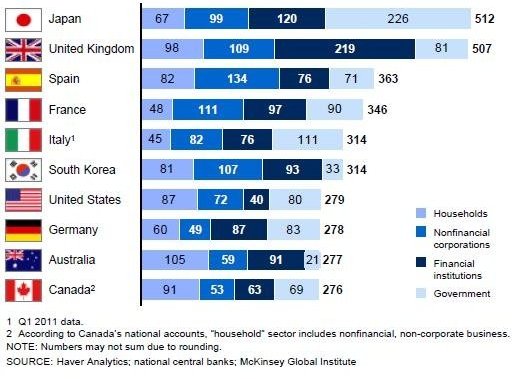

The chart below is the total debt as percent of GDP for the 10 largest mature economies. Greece isn’t even worth an honourable mention when placed alongside the truly gargantuan debts of Japan and the UK – on a per capita or absolute basis.

Is Even More Bad News Possible for Japan?

Sadly the answer appears to be yes. Deteriorating demographics with the attendant upward pressure on government spending and a move to sustained current account deficits – all in a low growth environment – have combined to create the perfect storm for Japan’s fiscal position – its bad and getting worse rapidly.

Agcapita Farmland Fund III

Farmland increasingly is in the news as more investors come to appreciate the superior qualities of the asset class – including low return volatility, diversification benefits due to a limited correlation to public equities and good risk adjusted returns. Agcapita Fund III is currently open and RRSP eligible.

- Residents in BC, Alberta, Saskatchewan or Manitoba – CLICK HERE to be contacted with more info.

- Resident in Ontario and an Accredited Investor – CLICK HERE to be contacted with more info.

The Ontario Securities Commission has a detailed definition of Accredited Investor which can be found HERE. However in general Accredited Investor means:

- An individual who, alone or together with a spouse, owns financial assets worth more than $1 million before taxes but net of related liabilities or

- An individual, who alone or together with a spouse, has net assets of at least $5,000,000.

- An individual whose net income before taxes exceeded $200,000 in both of the last two years and who expects to maintain at least the same level of income this year; or

- An individual whose net income before taxes, combined with that of a spouse, exceeded $300,000 in both of the last two years and who expects to maintain at least the same level of income this year.

- An individual who currently is, or once was, a registered adviser or dealer, other than a limited market dealer

Some Quotable Quotes

Simply for entertainment value if nothing else, here is former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan describing the robust nature of the US housing market and the safety of mortgage backed securities – all shortly before the largest financial crisis in history driven by a collapse in US housing prices:

“I believe that the general growth in large [financial] institutions have occurred in the context of an underlying structure of markets in which many of the larger risks are dramatically — I should say, fully — hedged.”

“Even though some down payments are borrowed, it would take a large, and historically most unusual, fall in home prices to wipe out a significant part of home equity. Many of those who purchased their residence more than a year ago have equity buffers in their homes adequate to withstand any price decline other than a very deep one.”

“The use of a growing array of derivatives and the related application of more-sophisticated approaches to measuring and managing risk are key factors underpinning the greater resilience of our largest financial institutions …. Derivatives have permitted the unbundling of financial risks.”

“Improvements in lending practices driven by information technology have enabled lenders to reach out to households with previously unrecognized borrowing capacities.”

“Indeed, recent research within the Federal Reserve suggests that many homeowners might have saved tens of thousands of dollars had they held adjustable-rate mortgages rather than fixed-rate mortgages during the past decade, though this would not have been the case, of course, had interest rates trended sharply upward.”

Regards

Agcapita

Sarkozy: Problem Solved, Or… Germany to Sarkozy: It’s Not Over

The ISDA Steps Up

No Winners in Ugly Greek Debt Deal, Only Lessons

And By the Way, Close Your Borders

The Next Greek Tragedy

Orlando, Stockholm, Paris, and Staying Young

… (December 11, 2009) – Greece’s prime minister, George Papandreou, told reporters in Brussels on Friday that European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet and Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker see “no possibility” of a Greek default, Bloomberg News reported. Papandreou also said that there was no possibility of Greece leaving the euro area, according to the report.

… (January 29, 2010) – There is no bailout and no “plan B” for the Greek economy because there is no risk it will default on its debt, the European monetary affairs commissioner, Joaquin Almunia, insisted on Friday.

… (September 16, 2010) – “Restructuring is not going to happen. There are much broader implications for the eurozone should Greece have to restructure its debt. People fail to see the costs to both Greece and the eurozone of a restructuring: the cost to its citizens, the cost to its access to markets. If Greece restructures, why on earth would people invest in other peripheral economies? It would be a fundamental break to the unity of the eurozone.” – George Papaconstantinou, former Greek Finance Minister

… (March 9, 2012) – ISDA EMEA DC Says Restructuring Credit Event Has Occurred With Respect To Greece

… (This week) – Take your pick from scores of quotes from various EU leaders: “A Greek default has no real impact on the rest of the Eurozone. No other countries are at risk.” Or: “The contagion ‘domino effect’ from Greece no longer threatens the rest of Europe, according to Marco Buti, the director general for economic affairs at the European Commission. In addition, Portugal and Ireland were said to be ‘in a much better place,’ while the credibility of Spain and Italy had ‘increased.'”

The headlines are about Greece, but the real story is not Greece but who is next. European leaders were right to be worried only a short while ago about contagion effects of a Greek default to the entire Euro system, which of course they now say doesn’t exist. This week we look at Europe, and sort through the ever more fascinating implications of the news in today’s headlines.

Sarkozy: Problem Solved, Or…

Germany to Sarkozy: It’s Not Over

Greek is having an “orderly” default. The taxpayers of Europe are in theory going to lend €130 billion to Greece to pay back €100 billion in Greek debt that is owed to private lenders. Greece has to pass several difficult tests in order to get the money. €100 billion of debt to private lenders will be written off. Thus the net effect will be that they owe €30 billion more. How does this help Greece, except that they get €30 billion more they cannot pay?

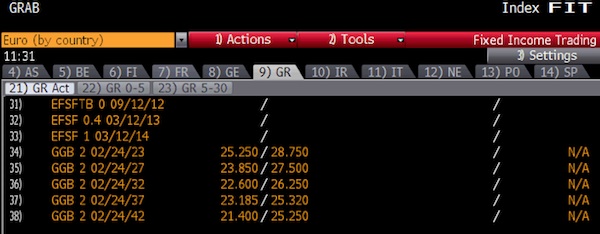

The “new” debt is already trading in the market, even though it has not actually been issued. (Don’t bother traders with messy details, just do the deal.) This page from Bloomberg is just too delicious not to print, sent to me courtesy of Dan Greenhaus of BTIG. It shows the new Greek bonds trading at over a 71-79% discount, depending on the length of maturity. Note this is AFTER the 53% haircut already imposed. That reads to me like the market value of original Greek debt is now between 12 and 14% of the original face value. Didn’t I write in this letter early last year that Greek debt would ultimately get a 90% haircut? Let me suggest to my critics that what was pessimistic back then may prove to have been optimistic at the end of the day.

Over 90% (some unconfirmed reports of as much as 95.7%) of Greek bondholders offered their bonds in the swap. The remaining bond holders will be forced by the Greek government to take the deal under a collective action clause, or CAC. But that 90%+ participation rate of bond holders willing to take their lumps may be suspect, according to Art Cashin, writing this morning:

“Some savvy (but very cynical) traders think the heavy participation may have been structured. They posit that in order to keep the deal from falling apart, some banks, on government instructions, may have paid a premium to the ‘reluctant’ participants. That would get them out of the way and allow for more tenders by the buyers. No proof – just conjecture.”

Greece itself is in free fall. The “benefits” of austerity have not become apparent, as the Greek economy saw growth rates of -0.2% in 2008, -3.3% in 2009, -3.4% in 2010, -6.9% in 2011, and…? The 4thquarter of last year saw a GDP fall of 7.5%. Do you see a trend here? The Greek economy is down by almost one-fifth in less than five years. Unemployment has risen to 20%, and 50% among young people, many of whom are leaving the country. Resentment has grown among ordinary Greeks over the austerity medicine ordered by international creditors, which has compounded the pain. Greek papers are full of stories blaming Germany for their problems.

By any standard, what will soon be a 20% drop can be classified as a depression. There is nothing on the horizon to suggest things will turn around any time soon. The country’s public debt-to-GDP ratio currently stands at 160% of nominal gross domestic product, AFTER the debt restructuring. If Greece can find someone to lend them more money, it will only get worse.

The current agreement with the EU will not improve the economy, but require even more wage cuts, government spending cuts, and higher taxes and unemployment. The problem is that if Greece leaves the euro, those problems do not go away, they just take a different form. There is still a great deal of economic pain for Greece as a consequence of past decisions. It is sad, but there is no other choice, unless the rest of Europe or the world, through the IMF, simply gives Greece all the money they want. But then where do you stop?

The citizens of California have chosen to let a series of cities enter bankruptcy, severely cutting police and fire, health, and other services. Europe has had about all the pleasure of bailing out Greece that it can handle, and is clearly ready to say, “Enough!” It is all very sad, but that is the consequence of too much debt and leverage. And every nation is subject to that consequence if it does not keep its own fiscal and economic house in order. Every nation.

The ISDA Steps Up

The ISDA (the International Swaps and Derivatives Association) declared today that Greece is in official default. This is a derivatives-industry committee of 15 members, representing the largest banks and derivative buyers – all the usual suspects. I started to write last week about their hesitancy, but it was very technical and I thought it likely they would issue the ruling they did this week. There are a few things we should note about this decision.

First, there is a widespread misunderstanding that the ISDA is the final answer to whether a nation is in default. The correct answer is, it depends. Credit default swaps are contracts between two private parties . The actual original contract is the governing document. While most contracts named the ISDA as the final arbiter of default, there are many that did not. Some experts told their clients there was a problem with choosing a self-interested industry group to be the final judge, and were very specific in their contracts as to what constituted a default. (Thanks to Janet Tavakoli, who spent an hour late one night patiently explaining the arcana and minutiae of credit default swaps. She literally wrote the book – and not just one but three of them – on swaps.)

It does not take a finance major to understand that if you do not get your money paid back to you, there was a default of some kind. If the ISDA had not confirmed a default by Greece, they would have ceased to be relevant in any future contracts that were written. It will be interesting to see how contracts are structured in future.

Secondly, the number that keeps showing up in the press is that there are only $3 billion of credit default swaps on Greek debt. That is only half true. The reality is that there is a NET $3.2 billion of CDS on Greek debt. The total or GROSS amount of swaps written is estimated to be about $60-70 billion (Dan Greenhaus, Chief Global Strategist, BTIG). This is in the 4,323 contracts that are known about.

Of the net exposure, the loss is likely to be less than the $3.2 billion, unless Greek debt goes to absolute zero. But that does not tell the whole story. For instance, just one Austrian state-owned “bad bank,” KA Finanz, faces a hit of up to 1 billion euros ($1.31 billion) for the hole Greece’s debt restructuring punches in its balance sheet. That loss, which will be borne by Austrian taxpayers, is someone else’s gain. The net number means nothing to them – they lose it all, over a third of the expected total loss.

Every bank and hedge fund, insurance company, and pension fund has its own situation. Care to wager that the larger banks won’t win on this trade? My bet is that there will be $30 billion in losses, out of which maybe someone will make $27 billion in gains.

Will the counterparty that holds your offsetting CDS be able to pay? Will all taxpayers be so accommodating as Austria’s? Does anyone think that taxpayers will bail out a hedge fund that cannot pay its debt, if it sold protection and has to default?

Would that it was “only” a $3 billion loss spread among the largest losers. That would be trivial in the grand scheme of things. Will Greece really stress the system, as it was stressed in 2008? The answer is, not likely, since European taxpayers have found €100 billion to cover the debt and the ECB has printed over €1 trillion, which has postponed any debt crisis for the immediate future. But the question that we must ask in a few paragraphs is, how many more countries will have to restructure their debt?

No Winners in Ugly Greek Debt Deal, Only Lessons

Just a few hours ago, as I was finishing this letter, I came across this blog by Michael Casey at the Wall Street Journal, called “No Winners In Ugly Greek Debt Deal, Only Lessons.” It is very to the point, so let’s look as his opening comments:

“Technocrats in Athens, Berlin and Washington Friday are no doubt congratulating each other for designing a bond swap that slashed more than EUR100 billion off Greece’s debt mountain.

“But let’s not kid ourselves: the two-year story behind this debt restructuring is an ugly one of politicking and wasted time. There are no winners here, and there are already more losers arising from its far-reaching ramifications.

“There are, however, lessons to be learned from this unseemly string of events. The most important is that our financial system is still trapped by the dilemma posed by Too-Big-to-Fail banks – four years since the U.S. mortgage crisis. Financial sector lobbyists who argue that now is not the time to fix that dysfunctional system should have a thorough reading of the Greece story.

“Officials will crow that a higher-than-expected 83% of Greece’s old bonds was voluntarily tendered into this debt swap and so claim justification for triggering the collective action clauses that will force the remaining holders of Greek law securities into the exchange. But without those CACs hanging like Damocles’ Sword over them, and without the pressure that governments and national central banks brought to bear on banks and pension funds from Greece, Germany and France, would so many have willingly accepted a 73%-plus write-off?

“As Commerzbank CEO Martin Blessing recently put it, this deal was as ‘voluntary as a confession during the Spanish Inquisition.’

“Truth be told, Greece can rightly argue it had no choice but to use coercion. Any less than 95% participation and the European Union would not have approved the latest EUR130 billion bailout, leaving the country unable to pay its bills and thrust into a more damaging, disorderly default.”

And By the Way, Close Your Borders

The fabric of the European Union is becoming frayed around the edges. George Friedman of Stratfor has pointed out in writing for this site that immigration is a much higher priority among many European voters than maintaining the euro. It is not talked about in polite circles, but it shows up in the polls. In line with that thought, my friend Dennis Gartman, who has never been accused of being politically correct, asks some very hard questions. In a few paragraphs with the provocative heading “And By the Way, Close Your Borders Too While Your At It…” He writes:

“The enmity between Greece and her northern European ‘cousins’ such as Germany and Austria is already high and wide, but it is growing higher and wider by the moment. It is almost to the point where the polite bounds of political correctness are about to be broken asunder, for German and Austrian political figures are now asking that Greece seal her borders and stop the flow of ‘foreigners’ through Greece and into the rest of the EU.

“Yesterday, the Austrian Home Affairs Minister, Ms. Johanna Miki-Leitner, minced few words and opened the rather racist front when she said, ‘We need to put real political pressure on

Greece to implement their asylum authority as rapidly as possible. This border is as open as a barn door.’

“There you have it … out in the open for all to see: northern European dissatisfaction and open disdain for the South and for ‘foreigners’ generally. And it is not just Greece that the Austrians and Germans fear as a port of entry for ‘foreigners’ into Europe; they fear Italy too, for Italy has been a port through which North Africans, fleeing the lesser chaos of Tunisia but the greater chaos of Libya and of Egypt, have arrived in shockingly large numbers to European shores. Indeed, more ‘foreigners’ have gotten access to Europe through Italy than have through Greece, but for the moment it is easier for an Austrian official to take on Greece than it is to take on Italy, and so Greece bears the burden at this point.

“As the German Minister of Justice, Mr. Hans-Peter Friedrich, rather ominously said yesterday, ‘The question remains, what happens when a country is not capable of securing its borders, as we see in Greece. Is it possible to reinstate border controls? I want to clarify that this is still part of our discussion.’

“Which then raises the question: Will Germany take it upon itself to secure Greece’s borders? My word but we don’t want to go down that path now, do we?”

The Next Greek Tragedy

As noted above, European leaders are falling all over themselves to tell us that the Greek default does not in any way suggest that it is possible for another country to default.

Kiron Sarkar makes the following points, with which I agree, so let’s jump to him:

“Spain unilaterally set its 2012 budget deficit at 5.8% of GDP, much higher than the 4.4% previously agreed with the EU. The budget deficit came in at 8.5% last year, once again higher than the target of 6.0%. A ‘discussion’ between Spain and the EU is inevitable, especially as (to date) the EU has insisted that Spain stick to its prior commitment. Quite an interesting development, particularly as it has come on the same day that 25 out of 27 EU countries (excluding the UK and the Czech Republic) signed up to the ‘fiscal compact’ which, once approved by each country’s national Parliament (Ireland will need a referendum), will introduce the German-inspired ‘debt brake’ into their constitutions – basically commits the 25 EU countries to reduce borrowings and, indeed, balance their budget deficits.

“Spanish unemployment rose by a massive +2.4% MoM in February, with youth (under 25) unemployment over 50%, yep that’s 50%. The EU has a tough task. If it offers concessions to Spain, expect Portugal, Ireland, etc., etc. to submit their own ‘requests.’ However, I just can’t see how Spain can meet its prior commitment. Officially, GDP is forecast to be -1.0% to -1.7% this year, though in reality the actual outcome will be closer to (indeed may exceed) the more pessimistic forecasts.”

And the report from Portugal is not much better. This from Lew Rockwell (Feb. 3, 2012):

“Things are also unraveling very quickly in Portugal. Now there is talk that private investors will be required to take a ‘haircut’ on Portuguese debt as well.

“The following is from a recent article in the Telegraph…

“‘A report for the Kiel Institute for the World Economy said Portugal would have to run a primary budget surplus of over 11pc of GDP a year to prevent debt dynamics spiralling out of control, even in a benign scenario of 2pc annual growth.

“‘Portugal’s debt is unsustainable. That is the only possible conclusion,’ said David Bencek, the co-author, warning that no country can achieve a primary budget surplus above 5pc for long. ‘We won’t know what the trigger will be, but once there is a decision on Greece people are going to start looking closely and realize that Portugal is the same position as Greece was a year ago.'”

“Sadly, that article is exactly right. Portugal is marching down the exact same road that Greece went down. The yield on 5-year Portuguese bonds is now up to an all-time record 19.8 percent. A year ago, the yield on those bonds was only about 6 percent. This is the same thing that happened to Greece. A year ago, the yield on 5-year Greek bonds was about 12 percent. Now the yield on those bonds is more than 50 percent.”

The world is facing a debt crisis unlike anything ever seen before, and Europe is right at the center of it.

Italy can pull out of its tailspin, but it will need help from the ECB in the form of debt issued at lower than current market rates. But if you give it to Italy, must not you do the same for Spain and Portugal? And while their economies are markedly worse, their government debt-to-GDP ratios are nowhere near as bad. And don’t even get me started about France, which becomes a crisis of biblical proportions by the middle of the decade. Let me note that France is not Greece. It actually is too big to save. France will make a difference when it enters its problem period. And the probable election of Hollande does nothing to alleviate any concerns. (Note: this will not prevent me from enjoying Paris in a few weeks, nor a hoped-for vacation in future years in the Loire Valley.)

There are only two ways that countries in Europe can get their deficits under control and begin to shrink their debt-to-GDP ratios. They can either grow GDP faster than the growth of their debt, or reduce their debt. How can Spain, with 20% unemployment and a projected 6% deficit, grow enough? Certainly not in the next few years. Portugal has the same problems. Austerity at the levels they will need will soon make growth even less likely, but borrowing more money is going to mean ever higher interest rates, unless the ECB is willing to print or Europe is willing to tax northern European countries to bail out the southerners. Try selling that one in an election campaign.

Because of the current willingness of European leaders to tap their taxpayers and of the European Central Bank to print money, a crisis has been averted, at least for the moment. For that, the US and the world can be grateful. The probability of a recession this year in the US is falling, as a crisis in the EU could have been the trigger that pushed a slow economy into recession.

But let’s make no mistake. The sovereign debt crisis is not over. Not in Europe, not in Japan, and not in the US. It is in a lull period. And don’t give me that old shibboleth, “The market is telling us that the crisis is over.” The market knows a lot less than many pundits believe. What did the market know in mid-2007? Not very much, although the warning signs were clear, at least to some of us.

Sadly, the focus of the crisis will now move on to other countries in Europe. The economic arithmetic of the peripheral countries is not much better than that of Greece only a few years ago. The pronouncements and assurances from European leaders are about the same as they were a few years ago. Total European debt is at 443%, well above US debt of 350%. European banks are leveraged over 30 to 1, at least double that of US banks, which are nerve-wracking enough.

It is the time of the Endgame. There will be contagion. It just comes with the territory.

Orlando, Stockholm, Paris, and Staying Young

I fly to Orlando for less than 24 hours tomorrow morning for a speech I will do with Endgame co-author Jonathan Tepper. It will be good to see him, and the conference (a private one) has several people I want to hear, as well. Then the next week to Stockholm and the following week staying over in Paris to attend the GIC conference on central banking, where I will be there just to learn. The title of the conference is Re-Examining Central Bank Orthodoxy for Unorthodox Times: Inaugural Meeting of The Global Society of Fellows (this is also a link, if you want more information). There are a few spots still left. It will be a most fascinating time to talk about central banking in Europe.

And then back to Texas for a few days, and the following weekend in San Francisco for the Life Extension Conference. I will make a few short remarks, but again am there mostly to learn. My intention is to be writing this letter for a very long time.

I am researching and writing away on the book on employment, and my suspicion is that the next month or so this letter will reflect that. I love the internet. You search something, which leads to something else, which leads… I am learning a great deal and hope to be able to get it into a smallish and very readable book.

This weekend we celebrate Tiffani’s birthday, with most of the kids gathered. Hurrah! As I close, I should note that Paris has seen more than a few crises over the centuries. I expect that it will survive the current problems just fine. I think a trip to the Louvre will be in order. And good times with both old and new friends. I am really looking forward to it.

It is time to hit the send button, as it is either late at night or early in the morning. My bed is calling, but I will get up and hit the gym. Have a great week.

Your really ready to write about something other than Greece analyst,

John Mauldin

johnmauldin@FrontlineThoughts.com“>John@FrontlineThoughts.com

Copyright 2012 John Mauldin. All Rights Reserved.

— Posted Sunday, 11 March 2012 | Digg This Article

Last month, Money Morning showed you how to use a technique called selling “cash-secured puts” to generate a steady flow of cash from a stock – even if you no longer own the shares.

It is a highly effective income strategy that can also be used to buy stocks at bargain prices.

But selling cash-secured puts does have a couple of drawbacks:

•First, it’s fairly expensive since you have to post a large cash margin deposit to ensure that you’ll be able to follow through on the transaction if the shares are “exercised.” Thus the name, “cash-secured” puts.

•Second, if the market – or the specific stock on which you sell the puts – falls sharply in price, you could have to buy the shares at a price well above their current value, taking a substantial paper loss.

Fortunately, there is a way to offset both these disadvantages while continuing to generate a steady income stream.

It’s called a “credit put spread” and it strictly limits both the initial cost and the potential risk of a major price decline.

I’ll show exactly how it works in just a second, but first I have to set the stage…

The Advantage of Credit Put Spreads

Assume you had owned 300 shares of diesel-engine manufacturer Cummins Inc. (NYSE: CMI) and had been selling covered calls against the stock to supplement the $1.60 annual dividend and boost the yield of 1.30%.

Let’s also assume that back in mid-January, when the stock was around $110 a share, you sold three February $120 calls because it seemed like a safe bet at the time.

However, when CMI’s price later moved sharply higher, hitting $122.07/share, your shares were called away when the options matured on Feb. 17.

That means you had to sell them at $120 per share to fulfill your call option. That might leave you with the following dilemma.

Thanks to the recent rally, the stocks you follow are too high to buy with the proceeds from your CMI sale. On the other hand, you also hate to forfeit the income you had been getting from the CMI dividend and selling covered calls.

You also decide you wouldn’t mind owning CMI again if the price pulled back below $120.

In this case, your first inclination might be to use the money from the CMI sale as a margin deposit for the cash-secured sale of three April $120 CMI puts, recently priced at about $4.90, or $490 for a full 100-share option contract.

That would have brought in a total of $1,470 (less a small commission), which would be yours to keep if Cummins remains above $120 a share when the puts expire on April 21.

That sounds pretty appealing, but…

The minimum margin requirement for the sale of those three puts – and, be aware, most brokerage firms require more than the minimum – would be a fairly hefty $8,190.

[Note: For an explanation of how margin requirements on options are calculated, you can refer to the Chicago Board Option Exchange (CBOE) Margin Calculator, which shows how the minimum margin is determined for a variety of popular strategies.]

Your potential return on the sale of the three puts would thus be 17.94% on the required margin deposit ($1,470/$8,190 = 17.94%), or 4.08% on the full $36,000 purchase price of the 300 CMI shares you might have to buy.

Either of those returns is attractive given that the trade lasts under two months – but you also have to consider the downside.

Should the market plunge into a spring correction, taking Cummins stock with it, the loss on simply selling the April $120 puts could be substantial.

For example, if CMI fell back to $100 a share, where it was as recently as early January, the puts would be exercised.

You’d have to buy the stock back at a price of $120 a share, giving you an immediate paper loss of $6,000 – or, after deducting the $1,470 you received for selling the puts, $4,530.

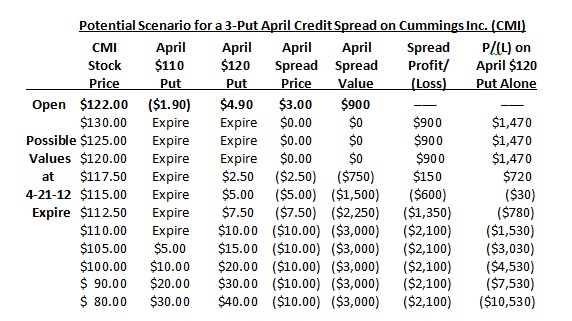

And, if CMI fell all the way back to its 52-week low near $80, the net loss would be $10,530. (See the final column in the accompanying table.)

All of a sudden, that’s not such an attractive prospect.

And that’s where a credit put spread picks up its advantage.

But selling cash-secured puts does have a couple of drawbacks:

•First, it’s fairly expensive since you have to post a large cash margin deposit to ensure that you’ll be able to follow through on the transaction if the shares are “exercised.” Thus the name, “cash-secured” puts.

•Second, if the market – or the specific stock on which you sell the puts – falls sharply in price, you could have to buy the shares at a price well above their current value, taking a substantial paper loss.

Fortunately, there is a way to offset both these disadvantages while continuing to generate a steady income stream.

It’s called a “credit put spread” and it strictly limits both the initial cost and the potential risk of a major price decline.

I’ll show exactly how it works in just a second, but first I have to set the stage…

The Advantage of Credit Put Spreads

Assume you had owned 300 shares of diesel-engine manufacturer Cummins Inc. (NYSE: CMI) and had been selling covered calls against the stock to supplement the $1.60 annual dividend and boost the yield of 1.30%.

Let’s also assume that back in mid-January, when the stock was around $110 a share, you sold three February $120 calls because it seemed like a safe bet at the time.

However, when CMI’s price later moved sharply higher, hitting $122.07/share, your shares were called away when the options matured on Feb. 17.

That means you had to sell them at $120 per share to fulfill your call option. That might leave you with the following dilemma.

Thanks to the recent rally, the stocks you follow are too high to buy with the proceeds from your CMI sale. On the other hand, you also hate to forfeit the income you had been getting from the CMI dividend and selling covered calls.

You also decide you wouldn’t mind owning CMI again if the price pulled back below $120.

In this case, your first inclination might be to use the money from the CMI sale as a margin deposit for the cash-secured sale of three April $120 CMI puts, recently priced at about $4.90, or $490 for a full 100-share option contract.

That would have brought in a total of $1,470 (less a small commission), which would be yours to keep if Cummins remains above $120 a share when the puts expire on April 21.

That sounds pretty appealing, but…

The minimum margin requirement for the sale of those three puts – and, be aware, most brokerage firms require more than the minimum – would be a fairly hefty $8,190.

[Note: For an explanation of how margin requirements on options are calculated, you can refer to the Chicago Board Option Exchange (CBOE) Margin Calculator, which shows how the minimum margin is determined for a variety of popular strategies.]

Your potential return on the sale of the three puts would thus be 17.94% on the required margin deposit ($1,470/$8,190 = 17.94%), or 4.08% on the full $36,000 purchase price of the 300 CMI shares you might have to buy.

Either of those returns is attractive given that the trade lasts under two months – but you also have to consider the downside.

Should the market plunge into a spring correction, taking Cummins stock with it, the loss on simply selling the April $120 puts could be substantial.

For example, if CMI fell back to $100 a share, where it was as recently as early January, the puts would be exercised.

You’d have to buy the stock back at a price of $120 a share, giving you an immediate paper loss of $6,000 – or, after deducting the $1,470 you received for selling the puts, $4,530.

And, if CMI fell all the way back to its 52-week low near $80, the net loss would be $10,530. (See the final column in the accompanying table.)

All of a sudden, that’s not such an attractive prospect.

And that’s where a credit put spread picks up its advantage.

Here’s how it works…

How to Create a Credit Put Spread

Instead of just selling three April CMI $120 puts at $4.90 ($1,470 total), you also BUY three April CMI $110 puts, priced late last week at about $1.90, or $570 total.

Because you have both long and short option positions on the same stock, the trade is referred to as a “spread,” and because you take in more money than you pay out, it’s called a “credit” spread.

And, in this case, the “credit” you receive on establishing the position is $900 ($1,470 – $570 = $900).

Again, that $900 is yours to keep so long as CMI stays above $120 by the option expiration date in April.

However, because the April $110 puts you bought “cover” the April $120 puts you sold, your net margin requirement is just $2,100 – which is also the maximum amount you can lose on this trade, regardless of how far CMI’s share price might fall. (Again, see the accompanying table for verification.)

That’s because, as soon as the short $120 puts are exercised, forcing you to buy 300 shares of CMI for $36,000, you can simultaneously exercise your long $110 puts, forcing someone else to buy the 300 shares for $33,000.

Thus, your loss on the stock would be $3,000, which is reduced by the $900 credit you received on the spread, making your maximum possible loss on the trade $2,100.

On the positive side, if things work out – i.e. CMI stays above $120 in April – and you get to keep the full $900, the return on the lower $2,100 margin deposit is a whopping 42.85% in less than two months, or roughly 278.5% annualized.

Plus, as is the case with most option income strategies, you can continue doing new credit spreads every two or three months, generating a steady cash flow until you’re ready to repurchase the stock at a more desirable price.

In this case, we say “ready” to repurchase because you’re never forced to buy the stock; you can always repurchase the options you sold short prior to expiration.

This strategy has substantial cost-cutting benefits when trading higher-priced issues like CMI, but it’s also a very effective short-term income strategy with lower-priced shares.

For example, with Wells Fargo & Co. (NYSE: WFC) trading near $31.50 late last week, an April credit spread using the $31 and $28 puts would bring in a net credit of 75 cents a share, or $225 on a three-option spread.

Since the net margin deposit on the trade would be just $675, you’d get a potential return of 33.3% in only seven weeks if WFC remains above $31 a share.

As you can see, credit put spreads are a great way to boost your gains while lowering your risks, especially in stable or rising markets.

So why not give yourself some credit.

Source http://moneymorning.com/2012/03/05/options-101-credit-put-spreads-can-boost-your-gains-and-lower-your-risk/

Money Morning/The Money Map Report

©2012 Monument Street Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Protected by copyright laws of the United States and international treaties. Any reproduction, copying, or redistribution (electronic or otherwise, including on the world wide web), of content from this website, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of Monument Street Publishing. 105 West Monument Street, Baltimore MD 21201, Email:customerservice@moneymorning.com” target=”_blank”>customerservice@moneymorning.com

Here’s how it works…

How to Create a Credit Put Spread

Instead of just selling three April CMI $120 puts at $4.90 ($1,470 total), you also BUY three April CMI $110 puts, priced late last week at about $1.90, or $570 total.

Because you have both long and short option positions on the same stock, the trade is referred to as a “spread,” and because you take in more money than you pay out, it’s called a “credit” spread.

And, in this case, the “credit” you receive on establishing the position is $900 ($1,470 – $570 = $900).

Again, that $900 is yours to keep so long as CMI stays above $120 by the option expiration date in April.

However, because the April $110 puts you bought “cover” the April $120 puts you sold, your net margin requirement is just $2,100 – which is also the maximum amount you can lose on this trade, regardless of how far CMI’s share price might fall. (Again, see the accompanying table for verification.)

That’s because, as soon as the short $120 puts are exercised, forcing you to buy 300 shares of CMI for $36,000, you can simultaneously exercise your long $110 puts, forcing someone else to buy the 300 shares for $33,000.

Thus, your loss on the stock would be $3,000, which is reduced by the $900 credit you received on the spread, making your maximum possible loss on the trade $2,100.

On the positive side, if things work out – i.e. CMI stays above $120 in April – and you get to keep the full $900, the return on the lower $2,100 margin deposit is a whopping 42.85% in less than two months, or roughly 278.5% annualized.

Plus, as is the case with most option income strategies, you can continue doing new credit spreads every two or three months, generating a steady cash flow until you’re ready to repurchase the stock at a more desirable price.

In this case, we say “ready” to repurchase because you’re never forced to buy the stock; you can always repurchase the options you sold short prior to expiration.

This strategy has substantial cost-cutting benefits when trading higher-priced issues like CMI, but it’s also a very effective short-term income strategy with lower-priced shares.

For example, with Wells Fargo & Co. (NYSE: WFC) trading near $31.50 late last week, an April credit spread using the $31 and $28 puts would bring in a net credit of 75 cents a share, or $225 on a three-option spread.

Since the net margin deposit on the trade would be just $675, you’d get a potential return of 33.3% in only seven weeks if WFC remains above $31 a share.

As you can see, credit put spreads are a great way to boost your gains while lowering your risks, especially in stable or rising markets.

So why not give yourself some credit.

Source http://moneymorning.com/2012/03/05/options-101-credit-put-spreads-can-boost-your-gains-and-lower-your-risk/

Money Morning/The Money Map Report

©2012 Monument Street Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Protected by copyright laws of the United States and international treaties. Any reproduction, copying, or redistribution (electronic or otherwise, including on the world wide web), of content from this website, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of Monument Street Publishing. 105 West Monument Street, Baltimore MD 21201, Email:customerservice@moneymorning.com” target=”_blank”>customerservice@moneymorning.com

Only about two dozen of these securities exist… but double-digit yields are common.

I first uncovered this asset class years ago, back when I started my High-Yield Investing advisory in 2004. In October of that year, I added one of these securities to my portfolio at $41.33. I sold it for $64.51 about two years later. Along with $9.93 in distributions, my total returns were just over 80%.

Another one of these rare investments has also done well for current High-Yield Investing subscribers. I added it to my portfolio in late October 2010. I’ve received $4.28 per unit in distributions and the price has soared. So far, total returns are more than 50% in just 16 months.

I like to return to investment ideas that have done well for me. So it comes as no surprise that I’m again looking into one of the highest-yielding, yet rarest, income investments on the market — royalty trusts.

These trusts are designed for one thing: to pay out royalties, or a share of production revenues, from a field of existing oil and natural gas wells.

The first trust debuted in 1979. Amazingly, even after more than 30 years there are still only about two dozen publicly traded oil and gas royalty trusts. And between 1999 and 2007, no new royalty trusts were created.

But in the past year, there has been a small renaissance in royalty trusts. I count four new trusts that have come to market in the last two years alone.

For income investors, the sudden surge of interest is good news. Routinely providing yields of about 10% or more, royalty trusts can seem too good to be true. Why, then, are oil and gas companies spinning off properties into publicly traded trusts?

Money.

Trusts allow the parent company to get full value for their reserves while also raising money, without diluting their common shares or going further into debt.

But there is one potential hang-up. By definition, these new trusts don’t have an established track record of generating cash flow from their reserves. Instead, you must rely on the company’s production projections and price assumptions, as stated in the prospectus.

That’s the downside. But it’s offset by at least two benefits.

First, recent trusts are being formed for a set life or “term” of 20 years. For example, SandRidge Permian Trust (NYSE: PER) was formed on May 12, 2011, and will dissolve by March 31, 2031. The parent company or sponsor endows the trust with proven reserves that have high-probability development opportunities to ensure the term is fulfilled.

In contrast, many older trusts formed in the early 1980s have consumed much of their original reserves. Although new production technologies have allowed them, in some cases, to draw more production from their reserves than originally anticipated, they still have a much shorter remaining reserve life. The average reserve life for older royalty trusts is about 8.3 years, versus 20 years for some of the newer trusts.

Once the reserves are used up, a trust expires and any remaining assets are distributed to unitholders. It can’t issue equity or debt to acquire new reserves.

A second benefit is some new trusts have created “subordinated units.” (Royalty trust shares are called units.) These units, which are held by the trust’s sponsor, support the distribution rate to common unitholders.

They work like this. When SandRidge Permian was created, sponsor SandRidge Energy (NYSE: SD) set aside 25% of the outstanding units for itself as subordinated units. These units are also entitled to receive distributions… with a catch.

The trust forecasts target distributions for several years in advance, based on projections of production volumes, commodity prices, the effect of hedges, expenses and taxes.

Then a subordination threshold is also established. For the SandRidge Permian Trust, the threshold is 20% below the target distribution. If the distribution ends up being less than the subordination threshold, the sponsor will make up the difference by reducing or foregoing the distribution on subordinated units. This way, there is some assurance that distributions will reach a pre-determined level should commodity prices fall.

In return, if the distribution is substantially higher than the target, the subordinated shares will receive an extra share of distributions.

These subordinated shares don’t last forever. The parent company retains these subordinated shares until new wells that the trust is also required to drill are completed. Then, a year later, the subordinated shares convert to common shares.

Now before you dive into any trust, there is plenty more to know. Taxes are a little trickier than with a common stock, and trusts will perform differently based on their hedging programs and their production mix of oil and natural gas (I detail all of this in my March issue of High-Yield Investing).

However, if you’re looking for a place to still capture high yields when interest rates are near zero, this sector may be small, but also holds plenty of promise.

[Note: If you’re interested in royalty trusts, be sure to learn more about StreetAuthority’s Top 5 Income Stocks for 2012 report. One stock we’ve selected is a royalty trust yielding double digits… another yields 8.8% and returned 13% during the bear market (when the S&P 500 fell -57%)… and a third holds stakes in dozens of infrastructure monopolies and has has paid more than 90 consecutive dividends. Visit this link to learn more.]

Good Investing!

![]()

Carla Pasternak’s Dividend Opportunities

Disclosure: Neither Carla Pasternak nor StreetAuthority own shares of the stocks mentioned above. In accordance with company policies, StreetAuthority always provides readers with at least 48 hours advance notice before buying or selling any securities in any “real money” model portfolio. Members of our staff are restricted from buying or selling any securities for two weeks after being featured in our advisories or on our website, as monitored by our compliance officer.