Daily Updates

This week I thought I would give you an Outside the Box with a more European flavor.

Dylan Grice of Societe Generale (based in London) is fast becoming one of my favorite writers. This thought-provoking piece makes us meditate on whether central banks will print money in response to the fiscal crisis in the developed world countries. I am not certain that all central banks will print with abandon, BUT we need to think about what happens if they do.

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

Print baby, print … emerging value and the quest to buy inflation

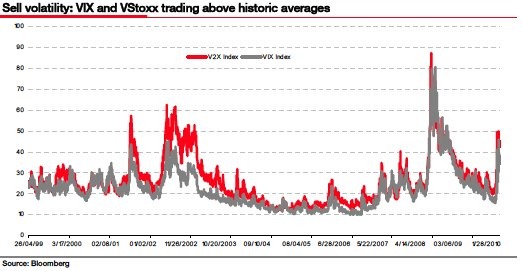

The eurozone’s fiscal farce offers a revealing glimpse of the future: sovereign crisis begets banking crisis begets central bank nose-holding while the printing presses roll!! More immediately though, it’s making equities look interesting again. Markets overall merely look less overvalued than they did. But undervaluation is emerging in some areas. And the VIX recently traded at 40. Selling out-of-the money puts at such levels (or higher), on companies you’re happy to own anyway is a good way to be paid for your patience.

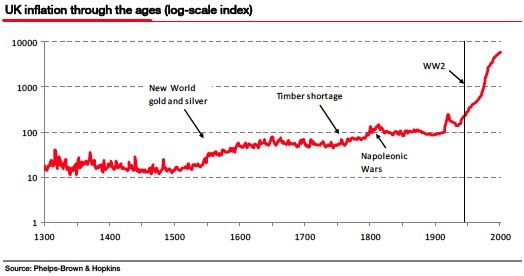

* The chart below shows the UK RPI from year 1300. From it, we can see that there have been inflationary episodes – the 16th century influx of new world gold and silver, the 18th century timber shortages, the early 19th century Napoleonic Wars – but that systematic CPI inflation is relatively new, and only started in earnest after WW2. This structural break coincides with the attainment of a voice in politics by ordinary people in developed economies: since voters rarely opt for economic pain, their elected representatives soon found they had to avoid it at all costs. Hence the relatively modern inflationary bias of “macroeconomic policy.”

* When that inflationary bias dictated lowering rates in the face of a threatened recession more quickly than you raised them in a recovery, it seemed harmless enough. But the crash of 2008 and its sovereign debt aftermath have changed everything. It’s difficult to exaggerate just how dirty the phrase deficit monetisation was when I studied economics at university: loaded with evil images of political irresponsibility and short-sightedness, it evoked the haunting spectre of catastrophic and ruinous hyperinflation. It’s what they did in Weimar Germany; it helped cause WW2; to say it had an image problem would be a grotesque understatement. No wonder it’s been rebranded as quantitative easing.

When faced with the prospect of a financial crash causing a nasty recession – or worse, a depression – few doubted that Anglo-Saxon central banks would do whatever was necessary, including breaking the taboo of deficit monetisation … sorry, engaging in quantitative easing. But the ECB was supposed to be different. The ECB was supposed to be genuinely independent. The ECB was modelled on the Bundesbank – itself forged in the white hot furnace of Weimar’s hyperinflationary trauma … So it was always going to be an interesting collision: what would happen when the unstoppable force of threatened financial wipeout met the immoveable object of the ECB’s hard-money dogma?

Well, the force stopped and the object moved … sort of. The market’s panic over eurozone debt subsided … for a while, and the ECB began quantitatively easing … kind of. The EU’s “shock and awe” $1trillion rescue was certainly a big number and reflected European governments going all in. But going all in is risky if you don’t have a strong hand, and the EU’s seems weak. Two-thirds of the rescue money comes from the EU itself, which means that the distressed eurozone borrowers are to be saved by more borrowing by … er … the distressed eurozone borrowers.

So there is virtually no new money coming into the European financial system. If a small bank goes down, the problem is solved when it is taken over by a bigger bank which injects new capital into it. If a bigger bank goes down, its problem is solved when it is taken over by the government, which injects new capital into it. If a government goes down … well, then we’re stuck. Where does the new capital come from now?

Enter central banks. In 2009, the BoE printed £200bn, thus completely financing the UK government deficit. It can’t have felt good about doing it but since the alternative scenario was so scary – financial meltdown and possibly IMF support – it held its nose and did it anyway. It said it was going to sterilise the intervention, but on discovering that such was the financial system distress it was unable to, it just carried on regardless. In the US, the Fed printed $1.25 trillion to monetise the problematic mortgage market. It also said it was going to sterilise the intervention, but like the BoE it soon found it couldn’t, and like the BoE continued anyway because the alternative financial meltdown scenario was too scary to contemplate.

Today, the ECB is buying insolvent eurozone government debt which it is promising to sterilise. Yet they face the same stark calculus faced by their Anglo-Saxon cousins in 2008. You can only worry about the economy’s ?price stability’ if the economy hasn’t already melted down! So here’s my prediction: they won’t sterilise, and the program will expand.

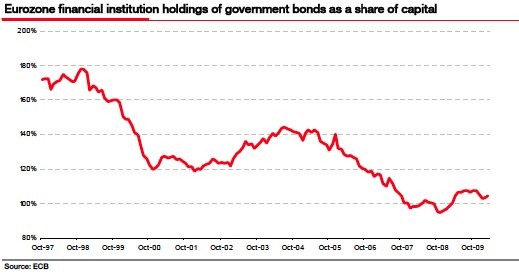

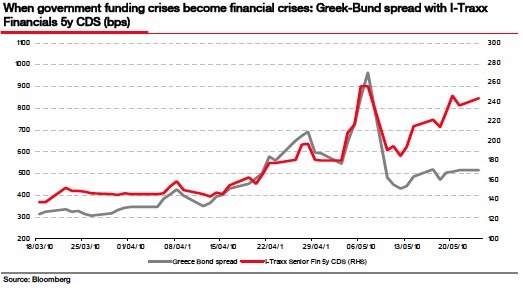

Since banks are typically stuffed full of government bonds (the first chart below shows eurozone financial institutions’ holdings of government securities as a share of capital), instability in government debt markets implies instability in bank balance sheets. So sovereign crises and financial crises are joined at the hip (second chart below). And since financial crises affect banks’ ability to lend, which poses obvious risks to the rate of employment, the need for a central bank response to the threat of financial collapse is clear:

- Print money

- Keep printing until the financial system stabilises

- Worry about removing liquidity later (and if removing liquidity stresses the financial system, go back to step 1)

What’s interesting is that central banks feel they have no choice. It’s not that they’re unaware of the risks (although there are profound behavioural biases working against them in their assessment of those risks). They’re printing money because they’re scared of what might happen if they don’t. This very real political dilemma is what is missing from the simplistic understanding of inflation as “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” It’s like they’re on a train which they know to be heading for a crash, but it is accelerating so rapidly they’re scared to jump off.

Incidentally, this is exactly the train Rudolf von Havenstein found himself on as President of the Reichsbank during the German hyperinflation. According to Liaquat Ahamed’s work on von Havenstein’s dilemma, in his majestic book ‘Lords of Finance’ ” … were he to refuse to print the money necessary to finance the deficit, he risked causing a sharp rise in interest rates as the government scrambled to borrow from every source. The mass unemployment that would ensue, he believed, would bring on a domestic economic and political crisis, which in Germany’s [then] fragile state might precipitate a real political convulsion.”

Most economists seem to think that QE puts us in uncharted waters. It doesn’t. Printing money to finance government expenditure is a very well trodden path which is as old as money itself: persistent monetisation causes inflation. Of course the current monetisation need not be persistent. Central banks can theoretically just stop it at any time.

But with government balance sheets in such a mess across the developed world (even with yields at historically unprecedentedly low levels), government funding crises are likely to be a recurring theme in the future. Since banks hold so much “risk free” government debt, those funding crises point towards more banking crises which point towards more money printing. When do they stop? When can they stop?

But what does it all mean? The question to my mind isn’t whether or not inflation will accelerate from here. If government balance sheets are in as big a mess as I think they are, inflation is inevitable. The more interesting question is what kind of inflation can we expect?

I hope to explore this properly in another note soon, but suffice to say for the time being that the typical framework economists use to think about inflation – which they proxy by changes in the CPI – is narrow, incomplete and fails to do justice to the richness of inflation as a concept. Asset markets (e.g. real estate, equities, etc.) are as prone to inflationist policy as product markets (indeed, in recent decades they have been far more prone to inflation than product markets), so one way of buying inflation – at least in its early stages – is to buy risk assets.

Of course, buying expensive risk assets on the view that they’re going to become more expensive is a dangerous game to play, but since government funding crises hammer risk assets while printing money inflates them, such funding crises should present decent value opportunities to buy into beaten up assets before the inflation ride.

Does today represent such an opportunity? We’re still nowhere near the distressed “all in” valuation levels I suspect the eurozone crisis merits (let alone the weakness in leading indicators Albert has been pointing out – what will a cyclical downturn do to government budgets?), but value is emerging and there are more stocks worth nibbling on than there have been for a while. The following chart shows the percentage of ‘bargain issues’1 in the nonfinancial FTSE World index has risen to just over 2% from under 1% a few months ago.

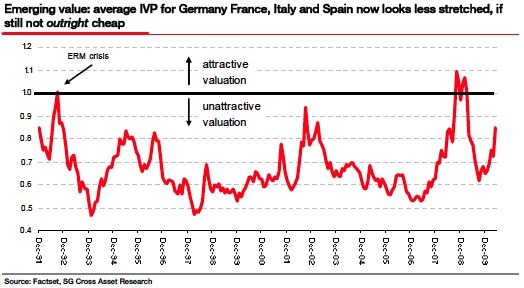

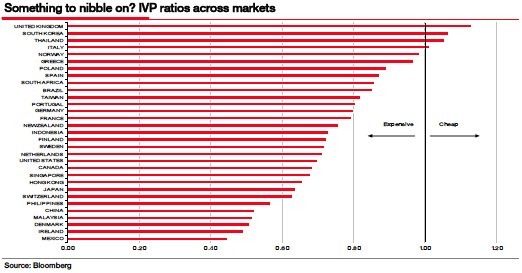

Regular readers know that I estimate intrinsic equity values for each of the stocks in my universe (I now use the FTSE World index and include emerging markets) which I compare to the stock prices. An intrinsic value to price ratio (IVP ratio) greater than one implies intrinsic value is higher than market prices and so equities are undervalued. The first chart below shows the average IVP ratio for France, Germany, Italy and Spain at 0.85 is more attractive than it’s been for some time, without being outright undervalued as it became during, say, the ERM crisis in 1992.

The next chart shows the cross section of valuations across all markets. It can be seen that the key European markets that are attractive remain the UK, Italy, and just about Norway.

The table at the end of the document shows stocks with estimated intrinsic values that are higher than current market prices (IVP>1) and these stocks deserve a closer look. I’ve constructed the intrinsic value model (a version of Steve Penman’s residual income model) on the assumption that I want a minimum 10% return. This is quite exacting, but the stocks in the table are all currently valued at levels consistent with such performance.

Finally, the one asset class unambiguously cheap right now is volatility. The VIX and the VStoxx are trading well above their long run averages. That doesn’t mean they can’t trade higher still but, whether you like my IVP approach or not, you’ll probably have a watch list of stocks with a clear price at which those stocks are cheap enough to buy. With the VIX above 40 – as it was earlier this week — it’s might be worth considering writing out-of-the money puts on those stocks. If you want to own them at those out-of-the money levels anyway, by writing generously priced options you’re being paid well for your patience.

Footnote:

I define a bargain issue as a stock with an estimated intrinsic value (see below) at least one-third higher than its market price (IVP>1.33), positive five year trailing EPS growth and positive expected residual income growth. These stocks have a backtested annualised return of 23% (list available on request).

John F. Mauldin

Outside the Box

“When the President is in trouble, the stock market is in trouble.” – The Late Elliott Janeway

Group Think and Disastrous Leaks

British Petroleum’s disastrous oil leak in the Gulf is giving us a sinister example of how futile American group-think can be. George Orwell coined the phrase ‘group think’ in his classic book 1984. It was his sarcastic word those times when we all think the same way, and we all get it wrong.

This horrible oil-rig accident is very serious: it’s a huge eco-disaster and it’s running out of control. There is no controversy about that. There is unanimity about getting it under control and stopping further damage.

What’s interesting is the American people’s group-think reaction. Somehow the people’s focus is turning toward President Obama; somehow the people seem to blame him. His popularity is dropping on the opinion poles for his failure to act. Or is it his failure to react? Or is it his failure to . . . to . . . ― “Well, we’re not quite sure what he should do, but he sure isn’t doing a very good job!” Isn’t it interesting how they seem to be blaming Mr. Obama for the oil-rig disaster?

And isn’t it interesting how President Obama feels the pressure of public group-think and has engaged BP’s management publicly, demanding that they do what they are already trying to do: namely, stop the disaster. And now, before the disaster is even under control, they’re talking about BP’s liability for the clean-up.

I am fascinated by the American public’s focus on the politicians. Surely they don’t really believe the President or the Senators and Congressmen can help. Or maybe they do. When Mr. Obama took control of the White House, the world was in the middle of a banking crisis. And by simply following the advice of his experts, he participated in saving the world from a banking calamity. Then, in the role of White Knight, he went on to chastise those banking leaders who caused the problem. And then he took several deep bows for his cool thinking under fire. He was so popular he was given the Nobel Peace Prize before he actually did anything.

Now the Gulf eco-disaster has placed his White Knight image in jeopardy: the president who can fix anything can’t fix this one. Nobody can fix it. Just as he took the credit for fixing the banking crisis, he is taking the blame for not fixing the oil-leak crisis. Group-think, American style: the president gets the credit for everything that goes well and gets blamed for everything that goes wrong. What interesting people our American cousins are. They love their heroes. And they love to despise their heroes when they disappoint.

Perhaps we Canadians can learn a lesson from them. In my book on investing Beyond the Bull, I put forth the idea of learning from others. Can we become better investors by learning from Americans’ impatience with their former heroes?

Remember the hero of the investment world in the 1990s? (Warren Buffet was only the icon.) The hero was your personal financial planner who became a financial White Knight leading us all on a crusade for personal wealth. All we had to do was buy the mutual funds he championed and hold them steadfastly until the End of Time. In financial Camelot, we would all retire rich and live happily ever after. I’m sure several Certified Wizards of Retirement Planning (CWRP) felt they should be nominated for a Nobel Prize.

But now it’s our stock market mutual fund investments that have blown up and are leaking our retirement savings. Have you noticed how equity mutual funds no longer advertise their ten-year returns? The stock market has become a retirement disaster for yesterday’s steadfast financial planners. Yesterday’s investment heroes have disappointed.

But we Canadians are different from Americans. They get disillusioned fast! We are slow to blame. They expect problems to be solved now! We will wait patiently and hope for things to get better. Americans criticise their president or fire their financial planners. We politely look the other way.

But my analogy doesn’t really work, does it? That oil well really is spewing black gunk into the Gulf’s rich waters and no White Knight has yet stopped it. But to stop the financial leak in our retirement plans, all we have to do is sell our stock market investments. It’s so easy. But financial group-think is hard to shake off when you’re part of the group. Maybe that’s why we Canadians are so patient with our investment disasters: we have no one to blame but ourselves.

Our advice? Invest in stock market mutual funds when the stock market is moving up. And when it’s not moving up, invest in something that is.

To order your copy of Beyond the Bull and the Five Levels of Investor Consciousness CD, or to sign up for Ken’s free monthly webinar, visit www.gobeyondthebull.com (Bullmanship Code = SS32).

This article and others by Ken are available at http://kennorquay.blogspot.com.

Contact Ken directly at ken@castlemoore.com.

“When the President is in trouble, the stock market is in trouble.” – The Late Elliott Janeway

Group Think and Disastrous Leaks

British Petroleum’s disastrous oil leak in the Gulf is giving us a sinister example of how futile American group-think can be. George Orwell coined the phrase ‘group think’ in his classic book 1984. It was his sarcastic word those times when we all think the same way, and we all get it wrong.

This horrible oil-rig accident is very serious: it’s a huge eco-disaster and it’s running out of control. There is no controversy about that. There is unanimity about getting it under control and stopping further damage.

What’s interesting is the American people’s group-think reaction. Somehow the people’s focus is turning toward President Obama; somehow the people seem to blame him. His popularity is dropping on the opinion poles for his failure to act. Or is it his failure to react? Or is it his failure to . . . to . . . ― “Well, we’re not quite sure what he should do, but he sure isn’t doing a very good job!” Isn’t it interesting how they seem to be blaming Mr. Obama for the oil-rig disaster?

And isn’t it interesting how President Obama feels the pressure of public group-think and has engaged BP’s management publicly, demanding that they do what they are already trying to do: namely, stop the disaster. And now, before the disaster is even under control, they’re talking about BP’s liability for the clean-up.

I am fascinated by the American public’s focus on the politicians. Surely they don’t really believe the President or the Senators and Congressmen can help. Or maybe they do. When Mr. Obama took control of the White House, the world was in the middle of a banking crisis. And by simply following the advice of his experts, he participated in saving the world from a banking calamity. Then, in the role of White Knight, he went on to chastise those banking leaders who caused the problem. And then he took several deep bows for his cool thinking under fire. He was so popular he was given the Nobel Peace Prize before he actually did anything.

Now the Gulf eco-disaster has placed his White Knight image in jeopardy: the president who can fix anything can’t fix this one. Nobody can fix it. Just as he took the credit for fixing the banking crisis, he is taking the blame for not fixing the oil-leak crisis. Group-think, American style: the president gets the credit for everything that goes well and gets blamed for everything that goes wrong. What interesting people our American cousins are. They love their heroes. And they love to despise their heroes when they disappoint.

Perhaps we Canadians can learn a lesson from them. In my book on investing Beyond the Bull, I put forth the idea of learning from others. Can we become better investors by learning from Americans’ impatience with their former heroes?

Remember the hero of the investment world in the 1990s? (Warren Buffet was only the icon.) The hero was your personal financial planner who became a financial White Knight leading us all on a crusade for personal wealth. All we had to do was buy the mutual funds he championed and hold them steadfastly until the End of Time. In financial Camelot, we would all retire rich and live happily ever after. I’m sure several Certified Wizards of Retirement Planning (CWRP) felt they should be nominated for a Nobel Prize.

But now it’s our stock market mutual fund investments that have blown up and are leaking our retirement savings. Have you noticed how equity mutual funds no longer advertise their ten-year returns? The stock market has become a retirement disaster for yesterday’s steadfast financial planners. Yesterday’s investment heroes have disappointed.

But we Canadians are different from Americans. They get disillusioned fast! We are slow to blame. They expect problems to be solved now! We will wait patiently and hope for things to get better. Americans criticise their president or fire their financial planners. We politely look the other way.

But my analogy doesn’t really work, does it? That oil well really is spewing black gunk into the Gulf’s rich waters and no White Knight has yet stopped it. But to stop the financial leak in our retirement plans, all we have to do is sell our stock market investments. It’s so easy. But financial group-think is hard to shake off when you’re part of the group. Maybe that’s why we Canadians are so patient with our investment disasters: we have no one to blame but ourselves.

Our advice? Invest in stock market mutual funds when the stock market is moving up. And when it’s not moving up, invest in something that is.

To order your copy of Beyond the Bull and the Five Levels of Investor Consciousness CD, or to sign up for Ken’s free monthly webinar, visit www.gobeyondthebull.com (Bullmanship Code = SS32).

This article and others by Ken are available at http://kennorquay.blogspot.com.

Contact Ken directly at ken@castlemoore.com.

1. GOLD IS RETURNING TO ITS TRUE HISTORIC ROLE AS MONEY

The role of gold in society was succinctly summed up by J.P. Morgan in 1912 when the renowned financier stated that “Gold is money and nothing else.” Ironically,

he made that comment one year before the U.S. Federal Reserve was created. There have been long periods (1980- 2000 being one) when this immutable fact was dismissed. The fact remains, however, that every fiat currency system in history has ended in ruins. Our current experiment seems to be headed down the same disastrous path, thus allowing gold to reemerge as a currency once again.

…..read 2-17 HERE

Ed Note: The S&P 500 index closed today June 15th at 1115.23 – above the 200 day moving average.

Gartman’s comment very early this morning June 15th below:

THE S&P AND ITS 200 DAY MOVING AVERAGE: Thanks to our friend David Wienke at Bache we note that the S&P has yet again failed from below its 200 day moving average. Should it fail again today we’ll pay even more bearish heed.

Further, the Dean of our industry, the wonderful Richard Russell (who is recovering from a recent stroke and whose swift return to full health we offer up prayers for) is manifestly fearful for the future of the stock market. Mr. Russell is and has been properly bullish when it is right to be bullish, and he has turned bearish when that too is meet and right. As Mr. Russell says of himself at the moment, he is “blatantly, almost boorishly bearish.” He went on to say that

Once the top has been put in, the market has nowhere to go but down…. And the top has definitely been put in. What do I do next? My job is to get my subscribers OUT of stocks any way I can. I’ve used logic, technical analysis with explanations; threats; pleading; history; tears; arguments from authority; warnings about the treacherousness of the bear. What’s left? I guess more work on my part…. On top of that, Warren [Buffett] continues to tell the world that stocks are a buy: Russell Comment: Buy’em yourself, Warren, and good luck.

So here we have it: Warren Buffett and Richard Russell at war in the markets. For now, our bet is with Mr. Russell.

For a Trial Subscription go to The Gartman Letter