Energy & Commodities

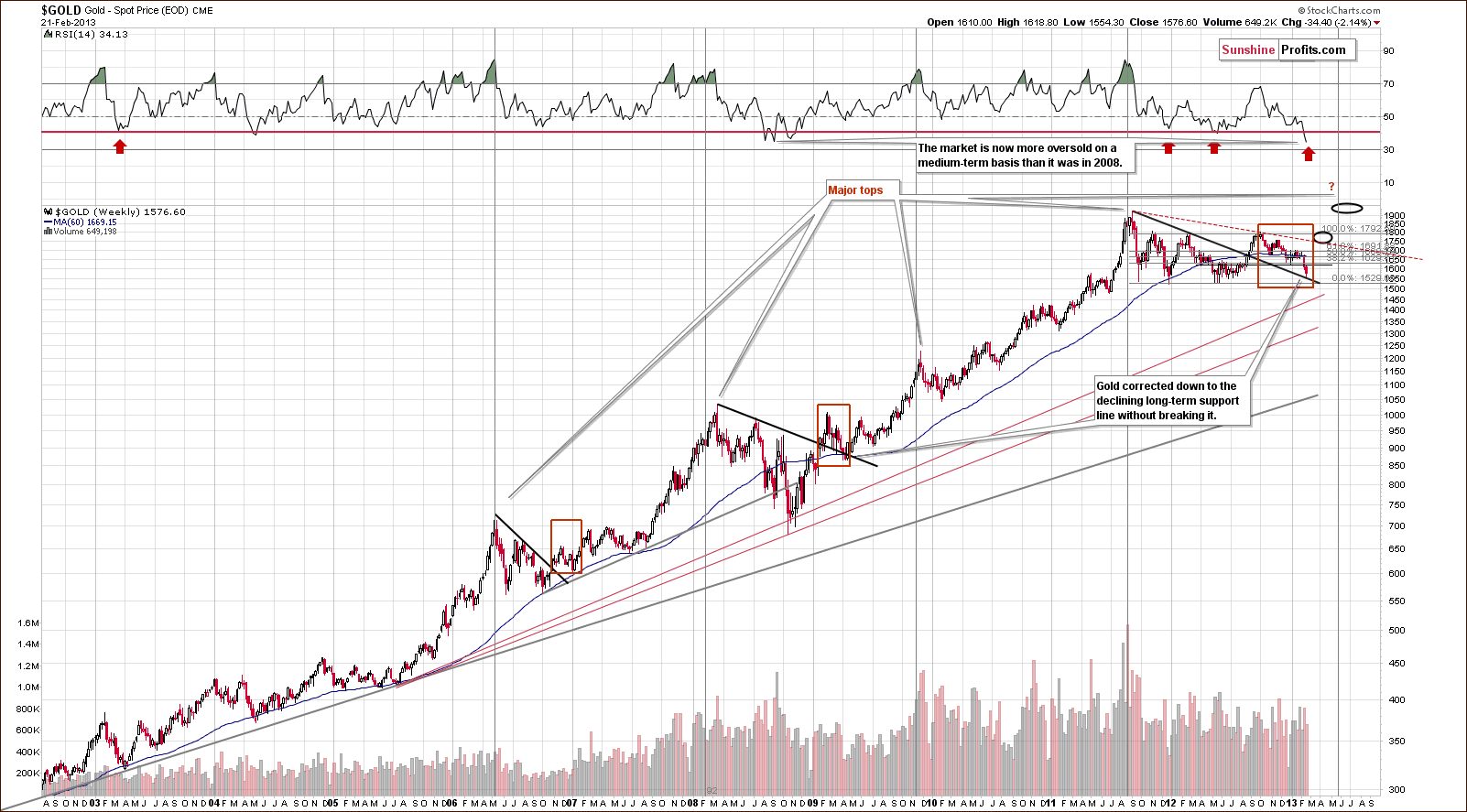

In our last essay we examined the situation in the U.S. Dollar Index (from many perspectives) and the Euro Index, as many times in the past it gave us important clues about future precious metals’ moves. Back then we wrote that the implications for the precious metal market were bearish just as the outlook for the Euro Index and just as it was bullish for the USD Index.

In our last essay we examined the situation in the U.S. Dollar Index (from many perspectives) and the Euro Index, as many times in the past it gave us important clues about future precious metals’ moves. Back then we wrote that the implications for the precious metal market were bearish just as the outlook for the Euro Index and just as it was bullish for the USD Index.

On the next trading day, after the essay was posted, gold, silver and mining stocks declined along with the European currency and hit their fresh monthly lows. Does it mean that the final bottom for the decline in gold, silver and mining stocks is already in?

Many times in our previous essays we wrote that if you want to be an effective and profitable investor, you should look at the situation from different perspectives and make sure that the actions that you are about to take are really justified. That’s why in today’s essay we’ll examine gold and silver mining stocks to find out what kind of impact they can have on precious metals’ future moves.

Additionally, it’s been almost a month since we wrote in greater detail about the precious metals mining stock sector, so we thought that you might appreciate an update. As a reminder, on Nov. 8 we wrote that the outlook remained bearish and even though we couldn’t rule out a few days of strength, it didn’t seem that a rally would be a sustainable development.

Let’s start with two of the most followed commodity stock indices – the Philadelphia Gold/Silver XAU Index and the AMEX Gold Bugs HUI Index (charts courtesy of http://stockcharts.com).

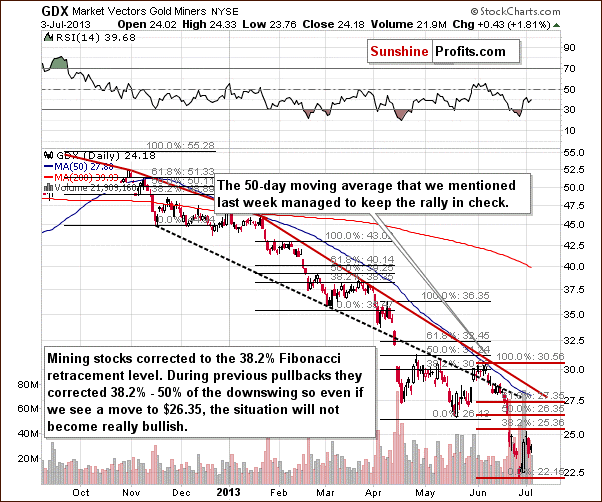

This week we saw a major breakdown below two critical support levels: the long-term rising support line and the 2013 low. Taking this fact into account, we can conclude that the implications are clearly bearish for the coming weeks.

Now, let’s have a look at the HUI Index. The chart below expresses a simplicity that betrays potential information on where this market may ultimately be heading. (Click on image for larger view)

In our previous Premium Update, we wrote that the HUI Index extended declines and dropped below the previous 2013 low, which was a very bearish sign. Back then we also mentioned that a similar breakdown in mining stocks preceded the plunge in the entire precious metals sector in April and taking this fact into account we could expect big moves to the downside in the days or weeks ahead.

Looking at the above chart, we see that we have indeed seen a big move to the downside, even though it’s been only a few days since the above was posted. This is another bearish confirmation, as back in 2008 the breakdown below the previous local low meant that the final sharp downswing was already underway. We expect the final bottom to be seen close to the 150 level.

What about the short term?

Let’s start by quoting what we wrote in Friday’s Premium Update:

From the short-term point of view, we see that the situation has deteriorated recently. At the beginning of the week mining stocks declined below the previous 2013 low and stayed there for three consecutive trading days. This means that the breakdown is confirmed at the moment and the implications are bearish.

As you can see on the above chart, miners reached the medium-term declining support line created by the August and September high – similarly to what we saw at the beginning of the month. Back then, this line triggered a consolidation (just like now); however, as it turned out it was just a pause within a short-term decline.

Taking this fact into account and combining it with the confirmed breakdown below the previous 2013 low, the current decline could become a major, medium-term decline.

It seems that we indeed see mining stocks in a major medium-term term decline as they dropped significantly this week.

There was even another breakdown – below the declining support line based on the August and September highs. The implications of the above chart remain bearish.

Finally, we would like to discuss the current situation in the gold-stocks-to-gold ratio.

On the above chart, we clearly see that the situation has again deteriorated in recent days. On Monday, the HUI-to-gold ratio dropped slightly below its previous 2013 low and we saw it close there on Tuesday as well. The breakdown is not confirmed at the moment but just one more daily close below the previous 2013 low will make the situation much more bearish.

Summing up, the medium-term trend remains down, the decline is quite likely to accelerate shortly and the outlook for the mining stocks sector is very bearish. It seems that practically all markets – gold, silver, main stock indices – are going down right now (except for crude oil, where we just saw a major breakout on huge volume) and mining stocks are declining along with them. Actually, they are leading the way.

Imagine that you retired in July 2012. Upon retirement, it was decided to place your hard-earned savings into a bond portfolio for safety and income. Let’s say that the portfolio is comprised of U.S. Treasury bonds and with an average maturity of about 8 ½ years.

So, how would you have done?

Despite receiving interest payments which would have yielded on average of about 1.8% of your initial investment, you would be down a total of 5.58% (see chart above).

That’s right, even when you add back the interest payments, you would be down a total of 5.58% over the first 18 months of your retirement!

If the volatility in the bond markets ended today and bond prices did not change, it would take three years’ worth of interest payments just to get back to breakeven. Four and a half years into retirement, and despite receiving interest over that time frame, your total return would be zero.

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Limited or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author’s judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Richardson GMP Limited, Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund.

Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.

For anyone who still thinks that something other than the U.S. Federal Reserve’s experiment with Quantitative Easing is helping to lift U.S. stocks, the chart above should quickly dispel that.

Since the introduction of QE1 back in later 2008, the growth of the Fed’s balance sheet as a result of QE almost perfectly overlays a chart of the S&P 500.

And, we know that earnings are not driving stocks. U.S. non-financial company earnings have been almost flat for the last two years now. (The largest financial companies have received massive government subsidies, which explains most of their earnings)

Now that U.S. stocks are breaking their recent trend, it will be interesting to see the extent of this correction. If there is enough of a selloff, the graph above will start to exhibit a deviation between the amount of QE and stock prices. That might be an indictment of the lack of effectiveness of QE in putting the U.S. economy back on a long-term growth trajectory and in fixing U.S. unemployment. If the market does lose faith in QE, what will be the Fed’s Plan B?

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Limited or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author’s judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Richardson GMP Limited, Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund.

Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.

As a distant but interested observer of history and investment markets I am fascinated how major events that arose from longer-term trends are often explained by short-term causes. The First World War is explained as a consequence of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian-Hungarian throne; the Depression in the 1930s as a result of the tight monetary policies of the Fed; the Second World War as having been caused by Hitler; and the Vietnam War as a result of the communist threat.

As a distant but interested observer of history and investment markets I am fascinated how major events that arose from longer-term trends are often explained by short-term causes. The First World War is explained as a consequence of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian-Hungarian throne; the Depression in the 1930s as a result of the tight monetary policies of the Fed; the Second World War as having been caused by Hitler; and the Vietnam War as a result of the communist threat.

Similarly, the disinflation that followed after 1980 is attributed to Paul Volcker’s tight monetary policies. The 1987 stock market crash is blamed on portfolio insurance. And the Asian Crisis and the stock market crash of 1997 are attributed to foreigners attacking the Thai Baht (Thailand’s currency). A closer analysis of all these events, however, shows that their causes were far more complex and that there was always some “inevitability” at play.

Simply put, a financial crisis doesn’t happen accidentally, but follows after a prolonged period of excesses…

Take the 1987 stock market crash. By the summer of 1987, the stock market had become extremely overbought and a correction was due regardless of how bright the future looked. Between the August 1987 high and the October 1987 low, the Dow Jones declined by 41%. As we all know, the Dow rose for another 20 years, to reach a high of 14,198 in October of 2007.

These swings remind us that we can have huge corrections within longer term trends. The Asian Crisis of 1997-98 is also interesting because it occurred long after Asian macroeconomic fundamentals had begun to deteriorate. Not surprisingly, the eternally optimistic Asian analysts, fund managers , and strategists remained positive about the Asian markets right up until disaster struck in 1997.

But even to the most casual observer it should have been obvious that something wasn’t quite right. The Nikkei Index and the Taiwan stock market had peaked out in 1990 and thereafter trended down or sidewards, while most other stock markets in Asia topped out in 1994. In fact, the Thailand SET Index was already down by 60% from its 1994 high when the Asian financial crisis sent the Thai Baht tumbling by 50% within a few months. That waked the perpetually over-confident bullish analyst and media crowd from their slumber of complacency.

I agree with the late Charles Kindleberger, who commented that “financial crises are associated with the peaks of business cycles”, and that financial crisis “is the culmination of a period of expansion and leads to downturn”. However, I also side with J.R. Hicks, who maintained that “really catastrophic depression” is likely to occur “when there is profound monetary instability — when the rot in the monetary system goes very deep”.

Simply put, a financial crisis doesn’t happen accidentally, but follows after a prolonged period of excesses (expansionary monetary policies and/or fiscal policies leading to excessive credit growth and excessive speculation). The problem lies in timing the onset of the crisis. Usually, as was the case in Asia in the 1990s, macroeconomic conditions deteriorate long before the onset of the crisis. However, expansionary monetary policies and excessive debt growth can extend the life of the business expansion for a very long time.

In the case of Asia, macroeconomic conditions began to deteriorate in 1988 when Asian countries’ trade and current account surpluses turned down. They then went negative in 1990. The economic expansion, however, continued — financed largely by excessive foreign borrowings. As a result, by the late 1990s, dead ahead of the 1997-98 crisis, the Asian bears were being totally discredited by the bullish crowd and their views were largely ignored.

While Asians were not quite so gullible as to believe that “the overall level of debt makes no difference … one person’s liability is another person’s asset” (as Paul Krugman has said), they advanced numerous other arguments in favour of Asia’s continuous economic expansion and to explain why Asia would never experience the kind of “tequila crisis” Mexico had encountered at the end of 1994, when the Mexican Peso collapsed by more than 50% within a few months.

In 1994, the Fed increased the Fed Fund Rate from 3% to nearly 6%. This led to a rout in the bond market. Ten-Year Treasury Note yields rose from less than 5.5% at the end of 1993 to over 8% in November 1994. In turn, the emerging market bond and stock markets collapsed. In 1994, it became obvious that the emerging economies were cooling down and that the world was headed towards a major economic slowdown, or even a recession.

But when President Clinton decided to bail out Mexico, over Congress’s opposition but with the support of Republican leaders Newt Gingrich and Bob Dole, and tapped an obscure Treasury fund to lend Mexico more than$20 billion, the markets stabilized. Loans made by the US Treasury, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements totalled almost $50 billion.

However, the bailout attracted criticism. Former co-chairman of Goldman Sachs, US Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin used funds to bail out Mexican bonds of which Goldman Sachs was an underwriter and in which it owned positions valued at about $5 billion.

At this point I am not interested in discussing the merits or failures of the Mexican bailout of 1994. (Regular readers will know my critical stance on any form of bailout.) However, the consequences of the bailout were that bonds and equities soared. In particular, after 1994, emerging market bonds and loans performed superbly — that is, until the Asian Crisis in 1997. Clearly, the cost to the global economy was in the form of moral hazard because investors were emboldened by the bailout and piled into emerging market credits of even lower quality.

…because of the bailout of Mexico, Asia’s expansion was prolonged through the availability of foreign credits.

Above, I mentioned that, by 1994, it had become obvious that the emerging economies were cooling down and that the world was headed towards a meaningful economic slowdown or even a recession. But the bailout of Mexico prolonged the economic expansion in emerging economies by making available foreign capital with which to finance their trade and current account deficits. At the same time, it led to a far more serious crisis in Asia in 1997 and in Russia and the U.S. (LTCM) in 1998.

So, the lesson I learned from the Asian Crisis was that it was devastating because, given the natural business cycle, Asia should already have turned down in 1994. But because of the bailout of Mexico, Asia’s expansion was prolonged through the availability of foreign credits.

This debt financing in foreign currencies created a colossal mismatch of assets and liabilities. Assets that served as collateral for loans were in local currencies, whereas liabilities were denominated in foreign currencies. This mismatch exacerbated the Asian Crisis when the currencies began to weaken, because it induced local businesses to convert local currencies into dollars as fast as they could for the purpose of hedging their foreign exchange risks.

In turn, the weakening of the Asian currencies reduced the value of the collateral, because local assets fall in value not only in local currency terms but even more so in US dollar terms. This led locals and foreigners to liquidate their foreign loans, bonds and local equities. So, whereas the Indonesian stock market declined by “only” 65% between its 1997 high and 1998 low, it fell by 92% in US dollar terms because of the collapse of their currency, the Rupiah.

As an aside, the US enjoys a huge advantage by having the ability to borrow in US dollars against US dollar assets, which doesn’t lead to a mismatch of assets and liabilities. So, maybe Krugman’s economic painkillers, which provided only temporary relief of the symptoms of economic illness, worked for a while in the case of Mexico, but they created a huge problem for Asia in 1997.

Similarly, the housing bubble that Krugman advocated in 2001 relieved temporarily some of the symptoms of the economic malaise but then led to the vicious 2008 crisis. Therefore, it would appear that, more often than not, bailouts create larger problems down the road, and that the authorities should use them only very rarely and with great caution.

Regards,

By Marc Faber via http://dailyreckoning.com/that-financial-crisis-was-no-accident

Marc Faber is an international investor known for his uncanny predictions of the stock market and futures markets around the world.