Personal Finance

In yesterday’s column, I debunked the myth that the stock market is long overdue for a pullback.

You might not believe it, but it’s true!

That being said, I’m afraid many of you walked away thinking that it’s simply a matter of (more) time passing by before a pullback or correction materializes.

That’s not the case, though.

You see, the mere passage of time doesn’t usher in pullbacks. It takes something specific to trigger them.

Or, as Deutsche Bank’s David Bianco says, dips might be inevitable, but “they don’t happen in absence of bad news or emerging risk.”

And right now, there are no emerging risks on the horizon. Don’t just take my word for it, though.

“We’ve got low inflation, improving domestic and global trends, [an] accommodative Fed, and it all adds up to a package that is a constructive backdrop for equities,” says Jim Russell, Senior Equity Strategist at U.S. Bank Wealth Management.

Indeed. That only leaves really bad news as a possible catalyst for a pullback or correction. So what type of bad news could ultimately trip up the stock market?

The opposite of what’s propelling it higher, of course!

Don’t Forget the Golden Rule

Forget a 5% pullback or a 10% correction. Some pundits and investors believe we’re in store for a massive 25% meltdown.

Fear mongers! Or maybe they’re just afraid of violating Warren Buffett’s golden rule of investing to “never lose money.”

Whatever their motivation, it doesn’t matter. The reality is, it’s going to take a sudden drop in corporate profits to collapse the stock market.

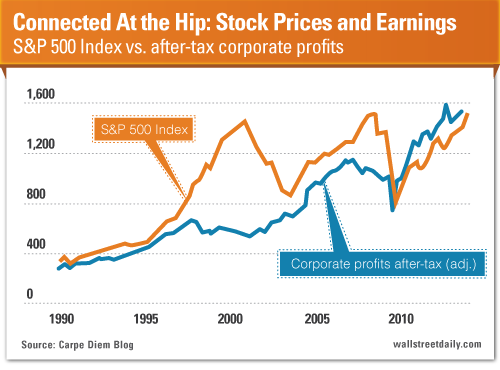

After all, stock prices ultimately follow earnings. I know I’ve told you that countless times already. But I’m afraid many of you still don’t believe it.

Maybe you just need to hear it said differently? If so, consider Larry Kudlow’s phrasing: “Profits are the mother’s milk of stocks.”

Too National Geographic for you? Ok. On second thought, maybe you just need additional proof.

Well, here it is, courtesy of Dr. Mark Perry at American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

As Perry explains, a one-to-one relationship exists between stock prices and after-tax corporate profits. For every increase of $1 billion in profits, the S&P 500 rises about 1 point. That is, with two notable exceptions: the dot-com bubble and the Great Recession.

As you can see, stock prices got too far ahead of corporate earnings during those periods. Sure enough, the market restored the relationship between corporate profits and stock prices by collapsing.

Or, put simply, stock prices ultimately followed earnings.

Here’s why all this matters…

According to Perry, “In the current bull market rally… corporate profits are consistent with stock market levels.” So the one-to-one relationship is in full effect. And that means there’s nothing abnormal about the current bull market. Corporate profits are driving stock prices.

By extension, as long as corporate profits keep increasing, stock prices should, too. And that’s exactly what analysts expect to happen…

After rising for more than three years, the consensus estimate calls for profits for S&P 500 companies to keep climbing to hit a record of $109.30 this year.

Bottom line: Absent a sudden drop in corporate profits – or the Fed unexpectedly pulling the plug on its quantitative easing initiatives – a pullback or correction is not going to magically materialize.

Stay tuned for tomorrow, though. I’ll share three key metrics to help you detect any deterioration in earnings – well ahead of the average investor.

Ahead of the tape,

Louis Basenese

Sign Up for Free Daily Newsletter HERE

About Wall Street Daily

In a World of Liars, the Truth Starts Here…

The harsh reality is that you’re being lied to every day – over and over again.

Wall Street is lying to you. The talking heads on television are lying to you. Your banker is lying to you. Your local Congressman is lying to you. Even your own broker is lying to you (mostly because he’s being lied to).

Consider: Behavioral science tells us that bankers and politicians are lying to us 93% of the time. And that Wall Street is 13 times more likely to tell a lie than the truth.

They win and we lose because our brains have been conditioned to cooperate in their con game.

But I believe you deserve the truth.

And to see that you get it, I’ve assembled a team of unbiased, seasoned investment professionals who pick apart the market’s biggest headlines on a daily basis.

Our mission?

To challenge Wall Street’s most widely accepted wisdom. And uncover the real intentions behind the greatest moneymaking machine of all time.

Along the way, we’ll also expose the profit trends others simply don’t have the experience to detect (or the courage to broadcast).

Bottom line, the most informed investor always wins. And getting you clued in is our top priority.

That’s why I’m personally challenging you to read our daily content for the next 30 days and see for yourself. If we’re doing our job effectively, you should notice it on your brokerage statement.

So don’t delay. To start getting a healthy dose of genuine, no-nonsense, 100% unbiased investment research and market commentary – i.e. THE TRUTH – justsign up below.

Ahead of the tape,

Louis Basenese

Chief Investment Strategist

We analyze whether gold has maintained its purchasing power as widely believed.

One of the characteristics that makes gold so appealing to investors is its store of value property (read Gold & Silver Continue To Frustrate Bears As Prices Hold Key Triple-Bottom Support). The yellow metal tends to maintain its value over time, say its proponents. Some even go as far as to say that 1 ounce of gold buys the same amount of bread, as it did at any time throughout history.

Now, whether this is true is debatable, but a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation yields some interesting results. For example, one widely reported statistic is that an ounce of gold bought 350 loaves of bread during the time of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon, who reigned during the sixth century BC.

How many loaves of bread does an ounce of gold buy today? Well, the calculation isn’t as simple one as one would think. There are so many different types of bread and prices for bread. Nevertheless, a look at the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ consumer price index suggests that on average, a pound of bread in the U.S. costs somewhere between $1.44 to $2.04, depending on whether it’s white or whole wheat.

If we take the average of those two prices, and further assume that a loaf of bread weighs 1.5 pounds, we reach a loaf price of $2.61. Now, some—particularly those in high-cost-of-living locales—will take issue with this price. In any case, that means that an ounce of gold—last trading for $1,585—can purchase 607 loaves of bread. A loaf of bread would have to cost roughly $4.50 to reach the 350-loaf-to-1 ounce-of-gold ratio.

This result tends to support the bullish view that gold maintains its value over time. However, even conceding that, others may draw the conclusion that gold is overvalued based on the somewhat-facetious gold/loaf-of-bread ratio.

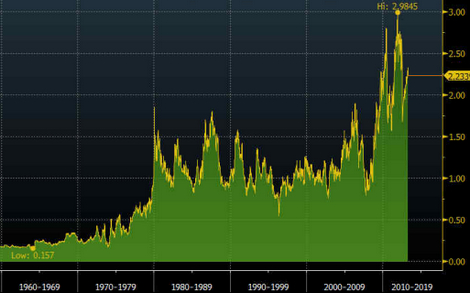

This whole discussion raises the question of how gold has performed versus other goods and gold’s relative value versus other goods. Sticking with the bread theme, the first ratio we take a look at is the gold/wheat ratio.

While we don’t have data on wheat prices going back to the 6th century BC, we have several decades of data that show gold is currently quite expensive relative to the grain. The period following 1980 is most noteworthy, in our view. Prior to 1971, gold traded at a fixed price in the U.S., and in the decade through 1980, high rates of inflation spurred the last great rally and peak in prices.

For the 25 years following 1980, the gold/wheat ratio was fairly stable, fluctuating between 90 and 150 (or alternately, 0.9 and 1.5 using a 100 bushel multiplier as the chart below does). Only recently has the gold/wheat ratio broken above that range.

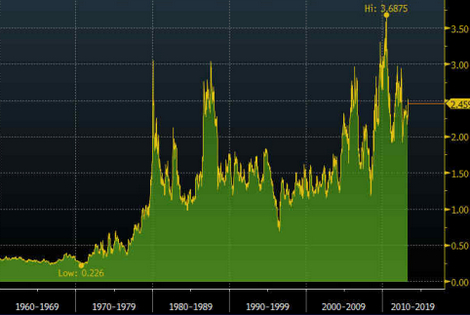

We see similar patterns in the gold/corn ratio and the gold/copper ratio. Both are near the upper ends of their respective ranges.

On the other hand, one ratio that paints a different picture is the gold/oil ratio. That ratio is well within its 30-year range.

Of course, there could be all sorts of reasons why any individual commodity fluctuates. Perhaps technology has pushed down the real cost of wheat, thereby depressing prices of that grain and concurrently pushing up the gold/wheat ratio.

Different people will draw different conclusions from these various ratios. But one thing is for sure: It’s hard to argue with the notion that gold tends to preserve its value over time. The evidence bears that out.

Good morning. Here’s what you need to know.

Good morning. Here’s what you need to know.

- Asian markets were mixed in overnight trading with the Bombay Stock Exchange down 1.15 percent to a seven-month low. The BSE surged almost 128 points, before tumbling 211 points. Europe is rallying and U.S. futures are modestly higher.

……read the rest HERE

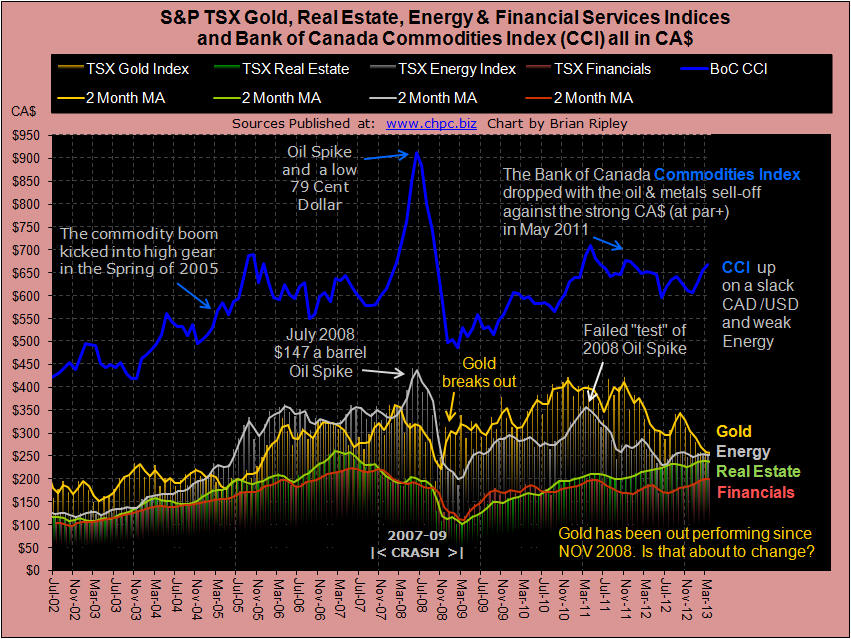

TSX Real Estate, Gold, Energy, Financial Services Indices and CRB

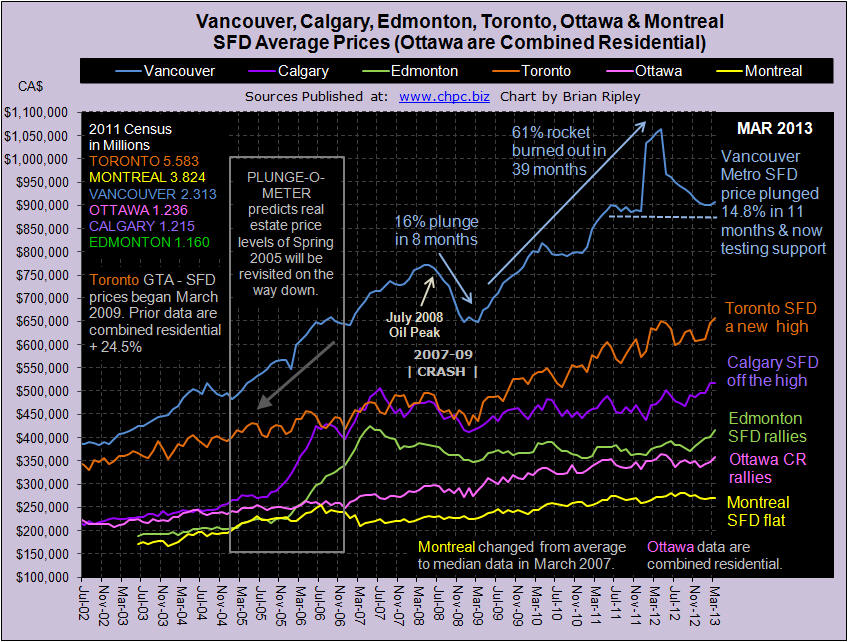

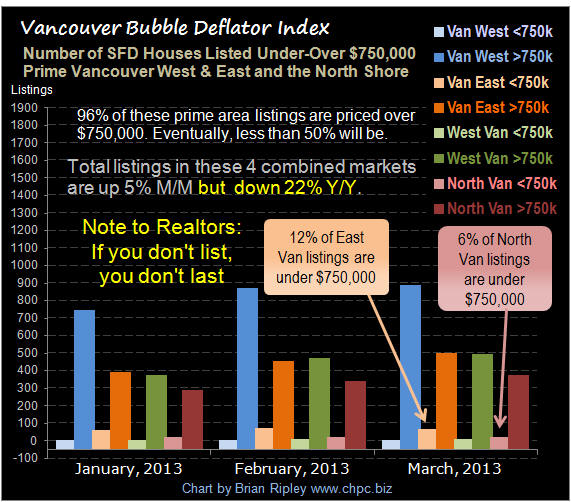

The Vancouver Bubble Deflator

In my select study, sellers are pricing high. 96% of these urban listings are still listed over $750,000. Listings available on the prime west side remain at elevated price levels driven by hopeful sellers looking for credulous buyers.

An era ended when the Soviet Union collapsed on Dec. 31, 1991. The confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union defined the Cold War period. The collapse of Europe framed that confrontation. After World War II, the Soviet and American armies occupied Europe. Both towered over the remnants of Europe’s forces. The collapse of the European imperial system, the emergence of new states and a struggle between the Soviets and Americans for domination and influence also defined the confrontation. There were, of course, many other aspects and phases of the confrontation, but in the end, the Cold War was a struggle built on Europe’s decline.

An era ended when the Soviet Union collapsed on Dec. 31, 1991. The confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union defined the Cold War period. The collapse of Europe framed that confrontation. After World War II, the Soviet and American armies occupied Europe. Both towered over the remnants of Europe’s forces. The collapse of the European imperial system, the emergence of new states and a struggle between the Soviets and Americans for domination and influence also defined the confrontation. There were, of course, many other aspects and phases of the confrontation, but in the end, the Cold War was a struggle built on Europe’s decline.

Many shifts in the international system accompanied the end of the Cold War. In fact, 1991 was an extraordinary and defining year. The Japanese economic miracle ended. China after Tiananmen Square inherited Japan’s place as a rapidly growing, export-based economy, one defined by the continued pre-eminence of the Chinese Communist Party. The Maastricht Treaty was formulated, creating the structure of the subsequent European Union. A vast coalition dominated by the United States reversed the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

Three things defined the post-Cold War world. The first was U.S. power. The second was the rise of China as the center of global industrial growth based on low wages. The third was the re-emergence of Europe as a massive, integrated economic power. Meanwhile, Russia, the main remnant of the Soviet Union, reeled while Japan shifted to a dramatically different economic mode.

The post-Cold War world had two phases. The first lasted from Dec. 31, 1991, until Sept. 11, 2001. The second lasted from 9/11 until now.

The initial phase of the post-Cold War world was built on two assumptions. The first assumption was that the United States was the dominant political and military power but that such power was less significant than before, since economics was the new focus. The second phase still revolved around the three Great Powers — the United States, China and Europe — but involved a major shift in the worldview of the United States, which then assumed that pre-eminence included the power to reshape the Islamic world through military action while China and Europe single-mindedly focused on economic matters.

The Three Pillars of the International System

In this new era, Europe is reeling economically and is divided politically. The idea of Europe codified in Maastricht no longer defines Europe. Like the Japanese economic miracle before it, the Chinese economic miracle is drawing to a close and Beijing is beginning to examine its military options. The United States is withdrawing from Afghanistan and reconsidering the relationship between global pre-eminence and global omnipotence. Nothing is as it was in 1991.

Europe primarily defined itself as an economic power, with sovereignty largely retained by its members but shaped by the rule of the European Union. Europe tried to have it all: economic integration and individual states. But now this untenable idea has reached its end and Europe is fragmenting. One region, including Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, has low unemployment. The other region on the periphery has high or extraordinarily high unemployment.

Germany wants to retain the European Union to protect German trade interests and because Berlin properly fears the political consequences of a fragmented Europe. But as the creditor of last resort, Germany also wants to control the economic behavior of the EU nation-states. Berlin does not want to let off the European states by simply bailing them out. If it bails them out, it must control their budgets. But the member states do not want to cede sovereignty to a German-dominated EU apparatus in exchange for a bailout.

In the indebted peripheral region, Cyprus has been treated with particular economic savagery as part of the bailout process. Certainly, the Cypriots acted irresponsibly. But that label applies to all of the EU members, including Germany, who created an economic plant so vast that it could not begin to consume what it produces — making the country utterly dependent on the willingness of others to buy German goods. There are thus many kinds of irresponsibility. How the European Union treats irresponsibility depends upon the power of the nation in question. Cyprus, small and marginal, has been crushed while larger nations receive more favorable treatment despite their own irresponsibility.

It has been said by many Europeans that Cyprus should never have been admitted to the European Union. That might be true, but it was admitted — during the time of European hubris when it was felt that mere EU membership would redeem any nation. Now, Europe can no longer afford pride, and it is every nation for itself. Cyprus set the precedent that the weak will be crushed. It serves as a lesson to other weakening nations, a lesson that over time will transform the European idea of integration and sovereignty. The price of integration for the weak is high, and all of Europe is weak in some way.

In such an environment, sovereignty becomes sanctuary. It is interesting to watch Hungary ignore the European Union as Budapest reconstructs its political system to be more sovereign — and more authoritarian — in the wider storm raging around it. Authoritarian nationalism is an old European cure-all, one that is re-emerging, since no one wants to be the next Cyprus.

I have already said much about China, having argued for several years that China’s economy couldn’t possibly continue to expand at the same rate. Leaving aside all the specific arguments, extraordinarily rapid growth in an export-oriented economy requires economic health among its customers. It is nice to imagine expanded domestic demand, but in a country as impoverished as China, increasing demand requires revolutionizing life in the interior. China has tried this many times. It has never worked, and in any case China certainly couldn’t make it work in the time needed. Instead, Beijing is maintaining growth by slashing profit margins on exports. What growth exists is neither what it used to be nor anywhere near as profitable. That sort of growth in Japan undermined financial viability as money was lent to companies to continue exporting and employing people — money that would never be repaid.

It is interesting to recall the extravagant claims about the future of Japan in the 1980s. Awestruck by growth rates, Westerners did not see the hollowing out of the financial system as growth rates were sustained by cutting prices and profits. Japan’s miracle seemed to be eternal. It wasn’t, and neither is China’s. And China has a problem that Japan didn’t: a billion impoverished people. Japan exists, but behaves differently than it did before; the same is happening to China.

Both Europe and China thought about the world in the post-Cold War period similarly. Each believed that geopolitical questions and even questions of domestic politics could be suppressed and sometimes even ignored. They believed this because they both thought they had entered a period of permanent prosperity. 1991-2008 was in fact a period of extraordinary prosperity, one that both Europe and China simply assumed would never end and one whose prosperity would moot geopolitics and politics.

Periods of prosperity, of course, always alternate with periods of austerity, and now history has caught up with Europe and China. Europe, which had wanted union and sovereignty, is confronting the political realities of EU unwillingness to make the fundamental and difficult decisions on what union really meant. For its part, China wanted to have a free market and a communist regime in a region it would dominate economically. Its economic climax has left it with the question of whether the regime can survive in an uncontrolled economy, and what its regional power would look like if it weren’t prosperous.

And the United States has emerged from the post-Cold War period with one towering lesson: However attractive military intervention is, it always looks easier at the beginning than at the end. The greatest military power in the world has the ability to defeat armies. But it is far more difficult to reshape societies in America’s image. A Great Power manages the routine matters of the world not through military intervention, but through manipulating the balance of power. The issue is not that America is in decline. Rather, it is that even with the power the United States had in 2001, it could not impose its political will — even though it had the power to disrupt and destroy regimes — unless it was prepared to commit all of its power and treasure to transforming a country like Afghanistan. And that is a high price to pay for Afghan democracy.

The United States has emerged into the new period with what is still the largest economy in the world with the fewest economic problems of the three pillars of the post-Cold War world. It has also emerged with the greatest military power. But it has emerged far more mature and cautious than it entered the period. There are new phases in history, but not new world orders. Economies rise and fall, there are limits to the greatest military power and a Great Power needs prudence in both lending and invading.

A New Era Begins

Eras unfold in strange ways until you suddenly realize they are over. For example, the Cold War era meandered for decades, during which U.S.-Soviet detentes or the end of the Vietnam War could have seemed to signal the end of the era itself. Now, we are at a point where the post-Cold War model no longer explains the behavior of the world. We are thus entering a new era. I don’t have a good buzzword for the phase we’re entering, since most periods are given a label in hindsight. (The interwar period, for example, got a name only after there was another war to bracket it.) But already there are several defining characteristics to this era we can identify.

First, the United States remains the world’s dominant power in all dimensions. It will act with caution, however, recognizing the crucial difference between pre-eminence and omnipotence.

Second, Europe is returning to its normal condition of multiple competing nation-states. While Germany will dream of a Europe in which it can write the budgets of lesser states, the EU nation-states will look at Cyprus and choose default before losing sovereignty.

Third, Russia is re-emerging. As the European Peninsula fragments, the Russians will do what they always do: fish in muddy waters. Russia is giving preferential terms for natural gas imports to some countries, buying metallurgical facilities in Hungary and Poland, and buying rail terminals in Slovakia. Russia has always been economically dysfunctional yet wielded outsized influence — recall the Cold War. The deals they are making, of which this is a small sample, are not in their economic interests, but they increase Moscow’s political influence substantially.

Fourth, China is becoming self-absorbed in trying to manage its new economic realities. Aligning the Communist Party with lower growth rates is not easy. The Party’s reason for being is prosperity. Without prosperity, it has little to offer beyond a much more authoritarian state.

And fifth, a host of new countries will emerge to supplement China as the world’s low-wage, high-growth epicenter. Latin America, Africa and less-developed parts of Southeast Asia are all emerging as contenders.

Relativity in the Balance of Power

There is a paradox in all of this. While the United States has committed many errors, the fragmentation of Europe and the weakening of China mean the United States emerges more powerful, since power is relative. It was said that the post-Cold War world was America’s time of dominance. I would argue that it was the preface of U.S. dominance. Its two great counterbalances are losing their ability to counter U.S. power because they mistakenly believed that real power was economic power. The United States had combined power — economic, political and military — and that allowed it to maintain its overall power when economic power faltered.

A fragmented Europe has no chance at balancing the United States. And while China is reaching for military power, it will take many years to produce the kind of power that is global, and it can do so only if its economy allows it to. The United States defeated the Soviet Union in the Cold War because of its balanced power. Europe and China defeated themselves because they placed all their chips on economics. And now we enter the new era.

Beyond the Post-Cold War World is republished with permission of Stratfor.”