Personal Finance

Too Tired to Think

“Gold Buying Up – consider this from Bloomberg:”

On Sunday night, we returned from a two-day horseback trip up into the Argentine mountains.

After 18 hours of riding over the worst terrain you can imagine – and sleeping on the hard stone floor of an unheated refuge at 9,500 feet – we showed up at the house bruised… worn-out… windburned… and sun beaten.

It was a great trip, in other words.

But your editor is too tired to think… or write.

In the sixth grade, at Owensville Elementary, our career path was decided for us. The entire class was told to write an essay. Pencils descended onto paper immediately. Except for our pencil, that is. We sat looking up the ceiling.

Mrs. Marshall came to our desk.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“Thinking,” we replied.

“Well, don’t think. Write.”

Which is about what we’ve been doing ever since.

But right now, we can barely sit. Writing will have to wait for tomorrow.

Please bear with us.

Gold Buying Up

In the meantime, consider this from Bloomberg:

Central banks bought the most gold since 1964 last year just before the collapse in prices into a bear market underscored investors’ weakening faith in the world’s traditional store of value.

Nations from Colombia to Greece, to South Africa, bought gold as prices rose for an 11th year in 2011, highlighting the reversal of a three-decade-long bout of selling that diminished the world’s biggest bullion hoard by 19%. The World Gold Council says it added 534.6 metric tons to reserves in 2012, the most in almost a half-century, and expects purchases of 450-550 tons this year, valued now at as much as $25.3 billion.

Whoa!

Central banks are printing newfangled money at a record rate. They are also buying gold, the old-fashioned money, at a record rate.

Question: What are they using to buy the old-fashioned money?

Answer: Directly or indirectly, they are using the printing-press money they create.

Small Potatoes

Here’s Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone:

Banks have been manipulating global interest rates, in the process messing around with the prices of upward of $500 trillion (that’s trillion, with a “T”) worth of financial instruments. When that sprawling con burst into public view last year, it was easily the biggest financial scandal in history – MIT professor Andrew Lo even said it “dwarfs by orders of magnitude any financial scam in the history of markets.”

That was bad enough, but now Libor may have a twin brother. Word has leaked out that the London-based firm ICAP, the world’s largest broker of interest-rate swaps, is being investigated by American authorities for behavior that sounds eerily reminiscent of the Libor mess. Regulators are looking into whether or not a small group of brokers at ICAP may have worked with up to 15 of the world’s largest banks to manipulate ISDAfix, a benchmark number used around the world to calculate the prices of interest-rate swaps.

Interest-rate swaps are a tool used by big cities, major corporations and sovereign governments to manage their debt, and the scale of their use is almost unimaginably massive. It’s about a $379 trillion market, meaning that any manipulation would affect a pile of assets about 100 times the size of the United States federal budget.

Mr. Taibbi is concerned with the way the swaps market is rigged. But that’s small potatoes, compared with the way the entire world financial system is tricked up.

More on this tomorrow, when we are able to sit down for longer than 10 minutes.

Regards,

![]()

Biill

Buy and Hold Is Dead

Let’s face it. The old ways of investing are obsolete. Thanks to an upcoming tax hike, courtesy of Obama and Congress, even blue-chip dividend stocks aren’t safe.

If you’re stuck in the old ways, you need to consider moving your portfolio out of stocks. I’ve found an investment that’s much safer — and more potentially lucrative.

In this video, I’ll show you an investment that’s gone up every year since 1950 — without touching the stock market.

Gold seems to be coming back fast. It rose $38 per ounce yesterday.

Of course, the Fed’s monetary meddling doesn’t work. And it will most likely cause a financial disaster.

But the biggest scandal of today’s central bank policy is that it is essentially the grandest larceny of all time.

The normal ways in which wealth is distributed may not be perfect, but they are the best nature can do. People earn it. They save it. They steal it. Or they get richer by investing.

Or they just get lucky…

Normally, in other words, wealth ends up being distributed in an unplanned and uncontrolled way. People do their best. The chips fall where they may.

But along come the central banks. They’re creating a new type of wealth. It is not wage income. It is not the product of capital investments. It is not the result of technology or productivity increases or hard work or self-discipline… or any of the other things that lead to wealth and prosperity.

Instead, it is created by the central bank “out of thin air.”

Not Your Grandfather’s Wealth

This new wealth is not like the regular kind. These chips don’t fall where they may; they get pushed around first.

The Fed creates new money (not more wealth… just new money). This new money goes into the banking system, pretending to have the same value as the money that people worked for. And people with good connections to the banks take advantage of the cheap credit this new money creates to aid financial speculation.

That’s what we’ve been watching in the financial markets for the last four years.

From Chris Martenson at PeakProsperity.com:

The central plank of Bernanke’s magic recovery plan has been to get everybody back borrowing, spending and “investing” in stocks, bonds and other financial assets. But not equally so, as he has been instrumental in distorting the landscape toward risky assets and away from safe harbors.

That’s why a two-year loan to the US government will net you only 0.22%, a rate that is far below even the official rate of inflation. In other words, loan the US government $10 million and you will receive just $22,000 per year for your efforts and lose wealth in the process because inflation reduced the value of your $10 million by $130,000 per year. After the two years are up, you are up $44,000 but out $260,000, for a net loss of $216,000.

That wealth, or purchasing power, did not just vanish: It was taken by the process of inflation and transferred to someone else. But to whom did it go?

Where do the chips come to rest?

While the Fed punishes honest savers, stocks and bonds rise every time a hint of more money printing is announced. And the yacht sales continue to rise, too, as long as the Fed promises more.

A Recovery for the Rich

The result? From Pew Research:

During the first two years of the nation’s economic recovery, the mean net worth of households in the upper 7% of the wealth distribution rose by an estimated 28%, while the mean net worth of households in the lower 93% dropped by 4%, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of newly released Census Bureau data.

From 2009-2011, the mean wealth of the 8 million households in the more affluent group rose to an estimated $3,173,895 from an estimated $2,476,244, while the mean wealth of the 111 million households in the less affluent group fell to an estimated $133,817 from an estimated $139,896.

These wide variances were driven by the fact that the stock and bond market rallied during the 2009-2011 period while the housing market remained flat.

Affluent households typically have their assets concentrated in stocks and other financial holdings, while less affluent households typically have their wealth more heavily concentrated in the value of their home.

From the end of the recession in 2009 through 2011 (the last year for which Census Bureau wealth data are available), the 8 million households in the US with a net worth above $836,033 saw their aggregate wealth rise by an estimated $5.6 trillion, while the 111 million households with a net worth at or below that level saw their aggregate wealth decline by an estimated $0.6 trillion.

There may be a “recovery” going on. But it is a recovery for the rich, not for the middle class.

Regards,

Bill

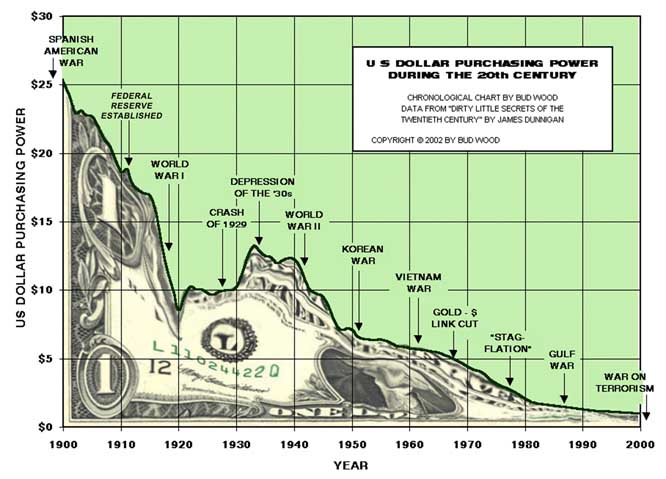

Ed: Found this chart of the US Dollar, which obviously needs to be updated

In the mid-1980s, a few years after I “decided to be rich,” I bought my dream house. It was a 4,000-square-foot chateau-styled, custom-built, five-bedroom home in a very nice gated neighborhood called Les Jardins in Boca Raton, Florida.

In the mid-1980s, a few years after I “decided to be rich,” I bought my dream house. It was a 4,000-square-foot chateau-styled, custom-built, five-bedroom home in a very nice gated neighborhood called Les Jardins in Boca Raton, Florida.

The cost of the house was about $600,000 – more than I ever imagined I could afford. But thanks to the success of a business I had started, I had socked away about $125,000. That was enough to cover the down payment and closing costs.

Telling the real estate agent “I’ll take it” gave me a great, memorable feeling of the power of wealth. I knew, even then, that this purchase would be a milestone in my life.

What I didn’t know was how many different lessons I would learn from it…

Deciding to buy my dream was euphoric. But signing the loan documents evoked a very different emotion: an ominous weight.

The title to this magnificent house was in my name. But I owned only one-fifth of it. The real owner was the bank.

I didn’t like the idea that if things went awry, I could lose “my” house to this corporation. So I decided to devote every extra dollar I made toward paying down the mortgage. I put no money away for my children’s education or my retirement. I didn’t even have an emergency fund. It all went toward my goal of really and truly owning my house.

What a great feeling it was when, only three years later, I handed that last payment to the bank. I would finally be rid of that burden, I thought. I would finally be master of my own domain.

But life had more lessons for me. Just a week or two after paying off the mortgage, I received my property tax assessment for the year. It was something like $22,000. “Holy cow,” I thought. “That’s more than K and I ever paid for rent. And I’ve got to pay this every year, without fail, as long as I own this house.”

The next week, I received a notice about the homeowner’s association fees: They would be going up to $4,000 per year. And then, the following week, I wrote checks to cover our monthly bills. These included about a half-dozen expenses that related directly to the house: electricity, gas, lawn maintenance, etc.

I realized that even after paying off a mortgage of $600,000, I was not in any way financially free. To possess and occupy that house was going to cost me more than $30,000 per year – for as long as I “owned” it.

I learned two important lessons from this experience:

- Holding title to something doesn’t mean you have absolute control over it.

- Having paid for something doesn’t mean it no longer costs you anything to use it.

Later, I realized that the same rules applied to buying a car. Getting title to one doesn’t mean you own it. And owning it doesn’t mean your car will be cost-free.

The same is true for boats and planes and beds and exercise equipment and machinery and so on. This rule applies to about everything you buy that cannot, like food or medicine, be consumed.

Thus, my happy delusion about ownership was shattered. But it wasn’t a bad thing. Not at all. It gave me a very useful insight into the cost of possessing things – an insight that has helped me make countless buying decisions since.

A New Way to Think About Ownership

Nowadays, when considering the purchase of a car or boat or a set of golf clubs, I don’t pretend that I will have them forever. I take a deep breath, calm down my greedy little heart, and make a realistic estimate about how many years I will actually use this desired object. I then calculate its total cost of ownership on a yearly basis.

In other words, rather than telling myself that this truck is going to cost me $25,000 (because that’s the sticker price), I do a full calculation of everything I’ll likely pay to own it for, say, 10 years, and arrive at what it will cost me, on an annual basis, to possess it.

I’m sure there are plenty of smart people who do the same thing. But I’ve never heard anyone say so. Nor have I read about it among the books on finance that I’ve read. So lacking a dictionary term for this idea, let’s create one. Let’s call it the cost of possession.

And to reiterate: The cost of possession is the full cost of using any non-consumable good, from a house to a car to a fountain pen, over a given period of time.

I said that understanding this idea has helped me become a better buyer of things. Let me give you an example – an issue that comes up all the time that you may have wondered about yourself.

An Old Debate: Own or Rent?

Many people believe that owning a house is always better than renting one. They point out that when you own a house, you get the benefit of price appreciation.

“Why should I fork over several thousand dollars per month in rent if, at the end of the day, I have nothing to show for it?”

The answer to this question becomes clear once you apply the principle we’ve just discussed – the cost of possession – to the decision at hand.

Today, for example, I’m shopping for an apartment in New York City. K and I are looking for a pied-à-terre in downtown Manhattan so we can be close to two of our sons who live in Brooklyn. I could afford to buy the apartments we are looking at, but because I now think in terms of the cost of possession, I’m pretty sure that would be a bad deal.

A little bit of arithmetic will demonstrate what I mean. The apartments we are looking at are in the $1.3 million-$1.7 million range. To make calculations simple, let’s assume I bought an apartment for $1.5 million and held it for 10 years. What would be the cost of possessing it on a yearly basis?

The first step is easy. We take the $1.5 million price and subtract it from the net price I think I’d be able to sell it for in 10 years. Assuming an annual appreciation of 4%, the apartment would be worth $2,220,000. I would stand to make a profit (a capital gain) of $660,000.

That’s an argument for ownership. But now I have to figure in the opportunity cost of plunking down $1.5 million in cash. The opportunity cost refers to the money I would have made by investing that same $1.5 million in another investment or group of investments. Assuming I could get a 4% yield on that $1.5 million, I’d turn that into $2,220,000, too. At the end of the 10 years, it is a wash.

OK, it’s tied at one-to-one.

Now let’s look at the other costs of possession…

First, when you own real estate, you have property taxes. From what I’ve seen so far, I’d be paying about 1.5% on the appraised value of the apartment. The appraised value would very likely be the price I paid for it. So that is a cost of $22,500 per year.

Then you have the association fees: The apartments I’m looking at average about $35,000 per year.

Then there is insurance, maintenance, and so on: I’m estimating that will run me $22,500 per year.

So the total cost of possessing that apartment on an ownership basis is $80,000 per year.

Now let’s look at renting…

You would think that if the rental market were “efficient,” the rental costs would amount to about the same thing: $80,000 per year. In fact, because of factors we don’t need to discuss here, it would cost me less than that to rent these apartments. My best guess is that it would cost me between $4,500 and $5,000 per month, including fees, to rent an apartment.

The bottom line: It would be about $20,000 per year cheaper to rent than to buy. Over a 10-year period, that’s a savings of $200,000.

So, in this case, renting is the better choice.

You can do the same analysis with cars. Rather than pretending that the sticker price of that Mustang you want is the cost of owning it, consider all the costs of possessing it, such as insurance, gas consumption, maintenance, and depreciation (i.e., cost versus resale value). Then make a realistic judgment about how many years you will keep it. And then you will have your annual cost of possession.

By approaching it this way, it will be very easy for you to compare leasing (renting) versus owning. You won’t make the mistake of thinking that either the sticker price or the monthly lease rate is your cost.

My housekeeper just found that out. She told the car dealer that she could afford to spend $300 per month and not a penny more. She further told him she could not afford a down payment. When he presented her with a car that met her expectations, she figured she had a good deal.

Two years later, when she discovered that she had already exceeded the mileage allocation for three years, she realized the truth. The car was going to cost her about $8,000 more over three years ($220 per month) than she had believed it would.

Understanding the cost of possession has saved me hundreds of thousands of dollars (if not millions) in these past 30-odd years. Discovering it was a big, big eye-opener. I hope this has had the same impact on you.

What I want you to take away from this essay is this: When making decisions about buying, renting, or leasing anything, always remember to include all of the costs involved. Then divide them by the number of years you expect to use the thing you are buying.

This will give you the real cost – the cost of possession. Once you get the knack for the arithmetic, it’s easy to do. You will make smarter decisions and have fewer regrets. And the salespeople you deal with will begrudgingly admire you!

Regards,

Mark Ford

Editor’s note: Mark recently formed a small group at The Palm Beach Letter where he shares step-by-step instructions to reaching a seven-figure net worth without stocks, options, or other risky investments. After just a few months, several subscribers have said they are on track to reaching their million-dollar goals. (One reader wrote in to say he made $60,000 in three weeks with one of Mark’s ideas. He expects to reach $1 million in just two years or less.)

Now, for a very limited time, Mark has opened this group to DailyWealth readers. Click here to learn more.

I grew up relatively poor, the second of eight children. My father earned $12,000 a year as a college professor. As a teenager, I was ashamed of our small house, my hand-me-down clothes, and my peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches.

I dreamed, literally dreamed, of living like a rich man.

And so, when I got my first job at age nine as a paperboy – and then at 12 as a lackey at the local carwash – I would spend my money on luxuries, like a pair of brand-new Thom McAn shoes.

I worked every chance I got through high school, and then worked two or three jobs during college and graduate school. I spent 80% of my money on necessities: food, clothes, and tuition. But I always spent a bit on little niceties. Even back then, I had the notion that I didn’t need to deprive myself now for some better life later.

I tell you this to emphasize a key part of the simple money-management system I’ve used to generate more than $50 million in wealth…

I don’t believe in scrimping severely to optimize savings. I believe you can live a rich life while you grow rich, so long as you are willing to work hard and you are smart about your spending.

I don’t believe in scrimping severely to optimize savings. I believe you can live a rich life while you grow rich, so long as you are willing to work hard and you are smart about your spending.

Think of the typical earning/spending/saving pattern of most wealth-seekers…

During their 20s, they spend every nickel of their modest income to make ends meet. At that age, it is nearly impossible to put aside money for the future.

During their 30s, their income increases. But this is also when they start a family. Expenses soar. There are more mouths to feed, a “family” car to buy, and the dreaded down-payment on a first house. They manage to save a little during these years, but not nearly as much as they thought they would.

If they work hard and make good career decisions, their income climbs much higher in their 40s and early 50s. They have more money to put aside for the future, but they are also tempted into buying newer cars, nicer clothes, more exotic vacations, and – the biggest wealth-stealer of them all – that dream house.

In their later 50s and 60s, their income plateaus or even dips… and they may have to start shelling out for college tuition. Aware that their retirement funds are being depleted rather than enhanced, they invest aggressively to try to make up the difference.

Finally, sometime in their mid- to late-60s, they realize that they don’t have enough money to retire. They have spent almost 40 years working hard and chasing wealth, but they never managed to attain it.

It’s sad, but it’s the reality for most people. And it is just as true for high-income earners (doctors, lawyers, etc.) as it is for working-class folks.

There are two lessons to be drawn from this:

First, it is very difficult to acquire wealth if you increase your spending every time your income goes up.

Second, setting unrealistic investing goals means taking greater risks. And taking more risks, contrary to what many pundits say, will almost always make you poorer… not richer.

The truth is, there is only a marginal relationship between how much you spend on housing, transportation, vacations, and toys, and the enjoyment you can derive from them.

My spending strategy is simple: Discover your own, less expensive way to live a rich life. By a “rich life,” I mean a life free from financial stress, but also filled with things that give you pleasure.

For example, good, restful sleep is essential for a happy life. Ideally, you’re going to spend around one-third of your life sleeping. So rather than “pay up” for an expensive car or an expensive necklace, buy a great mattress. By getting a great mattress (which can be had for less than $2,000), you’ll sleep as well as any billionaire… and be just as happy.

Your family can be just as happy in a house that costs $100,000 or $200,000 as opposed to one that costs $10 million or $20 million. Likewise, a $25,000 car will get you where you want to go just as well as a car that costs 10 times that amount. There are dozens of ways to live like a millionaire on a modest budget. If you learn those ways, you will have a tremendous advantage over everyone else at your income level.

Make smart spending decisions. Stop thinking that because you’re earning more money, you should be spending more. Your future wealth is determined by how much you save and invest, not by how much you spend.

So here’s what I’d like you to do: Figure out how much you need to spend every year to live your own personal version of a “rich” life. It might help to spend a few minutes thinking about all the things you truly enjoyed last year. If you are like me, you’ll find that almost all the things you enjoy require very little in the way of money. (Those are the true luxuries.)

Keep the biggest wealth-stealing expenses – like your house, your cars, and entertainment – to a necessary minimum. And eschew any expenditure that has a brand name attached to it. Brand names are parasites that gobble up wealth.

Don’t nod your head and promise to get to it sometime in the future. Do it today. Estimate, as well as you can, what you need to spend each year to have the life you want.

This is a number you must have firmly in your mind if you intend to be a serious wealth-builder.

This simple system for managing money can work for you if you commit yourself to it. As I said, it’s part of the system I used to build a net worth of more than $50 million – and it’s still working for me and everyone else I know who has tried it.

So today, spend the time it takes to establish your own approach to “living rich” now… and in the future.

Regards,

Mark Ford

Editor’s note: Last year, Mark formed a small group at The Palm Beach Letter to teach subscribers how to live rich while building wealth. The results have surpassed all expectations… Shaun Hansen wrote in to say he made $20,000 in less than 60 days – from home – with Mark’s techniques.

Mark has agreed – for a limited time – to open his complete “playbook” to DailyWealth readers at a generous discount. To review the full details and access this “life-changing material,” click here.

Further Reading:

Find more of Mark’s strategies for growing your wealth here…

A Three-Year Plan to Achieve Financial Independence

“Becoming a multimillionaire takes years. But breaking the chains of financial slavery can be done relatively quickly.”

How to Get a Little Bit Richer Every Day

“By following one simple rule of getting richer every day, I was able to do better than I ever expected… without a single day of feeling poorer than I was the day before.”

….and we are not seeing the Economic Growth story being supported in the Commodities Market

“There are some people now calling for DHIA 18,000 or 20,000 by year end,” “The S&P could then easily drop by 40%. the market needed the correction” starting in February or March, it did not correct, pull back, just dipped and buyers bought the dips into record territory.I thought maybe we were in a year like 1987, where the market goes up strongly between 1 Jan and 25 Aug. 25,. The market went up by 40% and then it crashed by 40% in 2 months’- Mr. Faber said in a recent TV interview.

Marc Faber – Gold Won’t Be Enough To Save You

Marc Faber : Gold is as Oversold as we were during the Crash in 1987

Marc Faber : The Government just fattens the pigs before they lead them to slaughter