Personal Finance

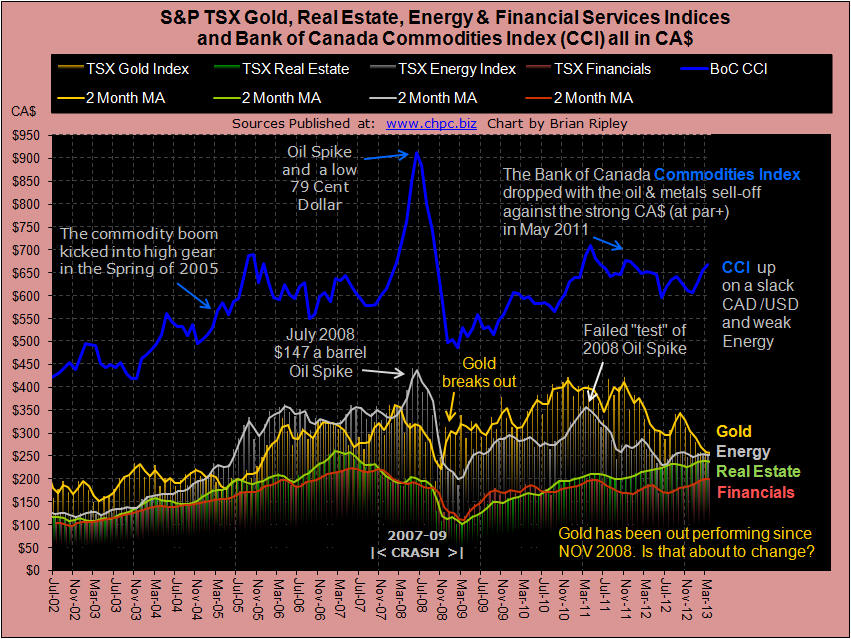

TSX Real Estate, Gold, Energy, Financial Services Indices and CRB

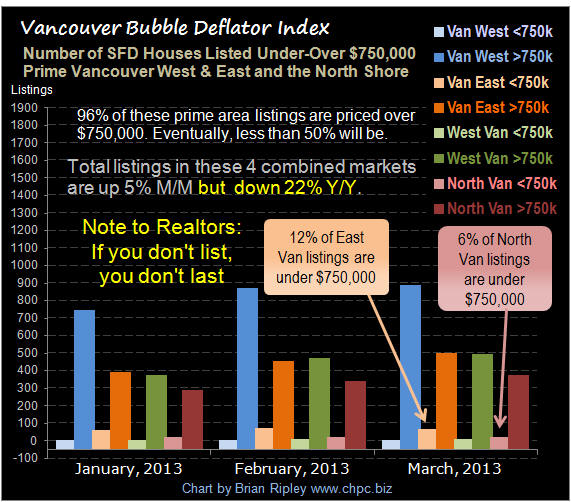

The Vancouver Bubble Deflator

In my select study, sellers are pricing high. 96% of these urban listings are still listed over $750,000. Listings available on the prime west side remain at elevated price levels driven by hopeful sellers looking for credulous buyers.

“MF Global, the depositors were also raided. It is nothing unusual. Philosophically I believe that we shouldn’t have deposit insurances, blanketed insurances by governments because it would force savers to be very careful with which bank they would deposit the money. The good banks would pay very low interest and take low risks and the banks that take high risks would have high interest. By the way, in Cyrus, banks were paying very high interest like in Lebanon at the present time I can get 6% on my deposits. So the depositors should have known that something is dangerous, but I would say that the principal now is very important to understand. Until now, the bailouts in Europe and the U.S. were at the expense of the taxpayer. And from now onwards, in my view, the bailouts will also be at the expense of the asset holders, the well-to-do people. So if you have money — like I am concerned — I am sure the governments will one day take away 20-30% of my wealth.” – in a recent interview

The majority of people don’t benefit from a rise in the Stock Market

“If you look at what happened in Cyprus, basically people with money will lose part of their wealth, either through expropriation or higher taxation,” explained Faber. “The problem is that 92 percent of financial wealth is owned by 5 percent of the population. The majority of people don’t own meaningful stock positions and they don’t benefit from a rise in the stock market. They are being hurt by a rising cost of living and we all know that the real incomes of median households have been going down for the last few years.” – in CNBC

The Revenues will continue to disappoint and that Earnings could very well disappoint quite badly

“Given the poor outlook in Europe and the slowdown in emerging economies, which has been confirmed by companies like Caterpillar (CAT) and McDonald’s (MCD), I would say that the revenues will continue to disappoint and that earnings could very well disappoint quite badly,”

“Once we realize that imperfect understanding is the human condition, there is no shame in being wrong, only in failing to correct our mistakes. – George Soros

Are we there yet?

Are we at the point where people might ignore the central banks?

Thankfully, maybe.

George Soros made a valid point to a CNBC interviewer recently. He noted the Bank of Japan made a dramatic move with monetary policy stimulus so that it wouldn’t be overlooked.

I think that idea was obvious. But Soros lends a lot of credibility to an idea based on his investment track record.

But he also may signal something more.

Being longer in his years, and evermore notorious as a left-wing political beacon, it seems Mr. Soros strains to toe the line laid down during media training.

In other words: he wants to say what’s on his mind but must choose his words carefully.

What I believe Soros would say if he were not in front of a camera is this:

“The influence of central bank stimulus policy is at risk of wearing off. While some may admit central banks did help to boost sentiment and loosen up credit markets, the measly pace of stop-and-go recovery is threatening to reveal that the effectiveness of central bankers’ tools is limited. The real risk now is that people aren’t encouraged to play along and money truly never makes it into the real economy as promised.”

Ok, that’s enough of pretending to be George Soros for one day.

The ongoing deliberations among Eurozone leaders and Troika officials tell us that austerity isn’t so popular and neither is dumping bailout liability onto taxpayers. Achieving the proposed resolution of a banking union will be difficult and should keep the European Central Bank very-much hogtied.

The measures undertaken by the Bank of Japan this week to target the monetary base have been tried before, to a degree. The measures didn’t work then. Now it seems the Japanese government is desperate and hopes the measures will succeed this time. Their overly-confident rhetoric also reeks of desperation.

The Federal Reserve is fully committed, but they can only do so much while they hold their breath and hope the unemployment situation improves sufficiently. They’ve got to be thinking the deflationary forces must be strong for their policies to have not turned up any inflation worth speaking of.

Earlier this morning the March US Nonfarm Payrolls were reported. It was a disappointment.

Instead of adding anywhere near the anticipated 200,000 new jobs, the economy only added 88,000. There were, however, upward revisions to January and February numbers.

The market is acting poorly, as one might have predicted.

I went into it thinking today’s report represented a bigger downside risk for markets than it has in a long time.

Why?

Because market mood has deteriorated this week. And markets seemed very vulnerable to a potential disappointing jobs number. Though we’ve seen widely-accepted “improvement” in the labor market, even the hiccups have been met with optimism; we’ve come to assume even a bad number is good because it means the Fed will keep on keeping on.

While no one expects the Fed to be planning its exit, the “Fed to the rescue” mentality may be overdone insofar as it influences short-term reaction to data and reports.

The expectations for US economic outperformance, relative to its peers, seems to have been the only crutch keeping the US market from giving way to Cyprus uncertainty and underwhelming price action in other asset classes.

So it’s not hard to see why today’s jobs number is pressuring US stocks (and even the US dollar at the same time.)

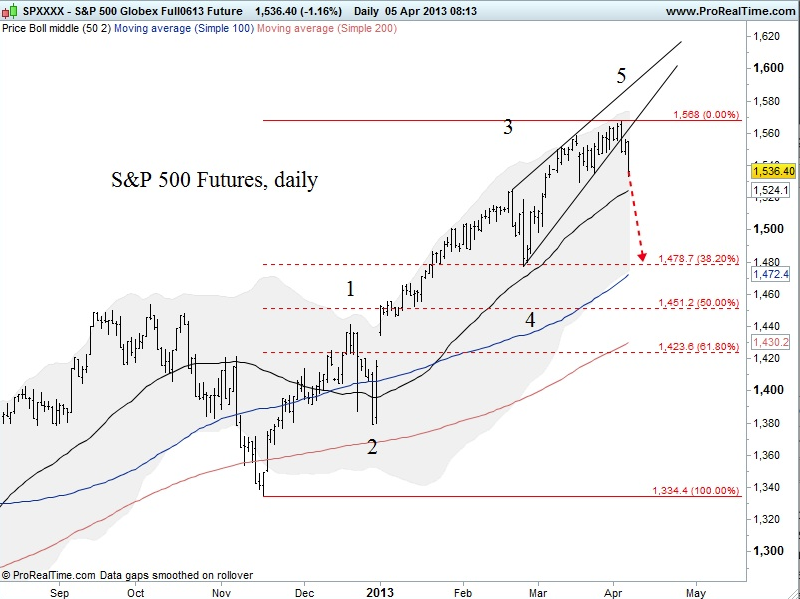

Besides, the market is certainly ripe for a correction and the technicals looked poised to drive the market lower (regardless of the jobs number). Below is a daily chart of the S&P 500 futures showing a fifth-wave extension/rising wedge set-up that suggests a significant reversal; first level of Fibonacci support comes in at 1,478:

It very much looks like the much-anticipated correction has begun.

I think that’s the way we have to play it right now, remaining open to more downside than generally expected.

But going forward, I suppose the question is this:

Do central banks have anything left in the toolbox the people can’t ignore?

I certainly don’t want to underestimate the potential central banks will concoct some sort of new and unprecedented strategy. Like I said of the BOJ above – I think policymakers (and politicians) have become desperate.

Of course, if the influence of central banks has truly run its course, then the market may have the opportunity to take over.

It’s just a correction for now. Play it. And reevaluate later.

-JR Crooks

An era ended when the Soviet Union collapsed on Dec. 31, 1991. The confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union defined the Cold War period. The collapse of Europe framed that confrontation. After World War II, the Soviet and American armies occupied Europe. Both towered over the remnants of Europe’s forces. The collapse of the European imperial system, the emergence of new states and a struggle between the Soviets and Americans for domination and influence also defined the confrontation. There were, of course, many other aspects and phases of the confrontation, but in the end, the Cold War was a struggle built on Europe’s decline.

An era ended when the Soviet Union collapsed on Dec. 31, 1991. The confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union defined the Cold War period. The collapse of Europe framed that confrontation. After World War II, the Soviet and American armies occupied Europe. Both towered over the remnants of Europe’s forces. The collapse of the European imperial system, the emergence of new states and a struggle between the Soviets and Americans for domination and influence also defined the confrontation. There were, of course, many other aspects and phases of the confrontation, but in the end, the Cold War was a struggle built on Europe’s decline.

Many shifts in the international system accompanied the end of the Cold War. In fact, 1991 was an extraordinary and defining year. The Japanese economic miracle ended. China after Tiananmen Square inherited Japan’s place as a rapidly growing, export-based economy, one defined by the continued pre-eminence of the Chinese Communist Party. The Maastricht Treaty was formulated, creating the structure of the subsequent European Union. A vast coalition dominated by the United States reversed the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

Three things defined the post-Cold War world. The first was U.S. power. The second was the rise of China as the center of global industrial growth based on low wages. The third was the re-emergence of Europe as a massive, integrated economic power. Meanwhile, Russia, the main remnant of the Soviet Union, reeled while Japan shifted to a dramatically different economic mode.

The post-Cold War world had two phases. The first lasted from Dec. 31, 1991, until Sept. 11, 2001. The second lasted from 9/11 until now.

The initial phase of the post-Cold War world was built on two assumptions. The first assumption was that the United States was the dominant political and military power but that such power was less significant than before, since economics was the new focus. The second phase still revolved around the three Great Powers — the United States, China and Europe — but involved a major shift in the worldview of the United States, which then assumed that pre-eminence included the power to reshape the Islamic world through military action while China and Europe single-mindedly focused on economic matters.

The Three Pillars of the International System

In this new era, Europe is reeling economically and is divided politically. The idea of Europe codified in Maastricht no longer defines Europe. Like the Japanese economic miracle before it, the Chinese economic miracle is drawing to a close and Beijing is beginning to examine its military options. The United States is withdrawing from Afghanistan and reconsidering the relationship between global pre-eminence and global omnipotence. Nothing is as it was in 1991.

Europe primarily defined itself as an economic power, with sovereignty largely retained by its members but shaped by the rule of the European Union. Europe tried to have it all: economic integration and individual states. But now this untenable idea has reached its end and Europe is fragmenting. One region, including Germany, Austria, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, has low unemployment. The other region on the periphery has high or extraordinarily high unemployment.

Germany wants to retain the European Union to protect German trade interests and because Berlin properly fears the political consequences of a fragmented Europe. But as the creditor of last resort, Germany also wants to control the economic behavior of the EU nation-states. Berlin does not want to let off the European states by simply bailing them out. If it bails them out, it must control their budgets. But the member states do not want to cede sovereignty to a German-dominated EU apparatus in exchange for a bailout.

In the indebted peripheral region, Cyprus has been treated with particular economic savagery as part of the bailout process. Certainly, the Cypriots acted irresponsibly. But that label applies to all of the EU members, including Germany, who created an economic plant so vast that it could not begin to consume what it produces — making the country utterly dependent on the willingness of others to buy German goods. There are thus many kinds of irresponsibility. How the European Union treats irresponsibility depends upon the power of the nation in question. Cyprus, small and marginal, has been crushed while larger nations receive more favorable treatment despite their own irresponsibility.

It has been said by many Europeans that Cyprus should never have been admitted to the European Union. That might be true, but it was admitted — during the time of European hubris when it was felt that mere EU membership would redeem any nation. Now, Europe can no longer afford pride, and it is every nation for itself. Cyprus set the precedent that the weak will be crushed. It serves as a lesson to other weakening nations, a lesson that over time will transform the European idea of integration and sovereignty. The price of integration for the weak is high, and all of Europe is weak in some way.

In such an environment, sovereignty becomes sanctuary. It is interesting to watch Hungary ignore the European Union as Budapest reconstructs its political system to be more sovereign — and more authoritarian — in the wider storm raging around it. Authoritarian nationalism is an old European cure-all, one that is re-emerging, since no one wants to be the next Cyprus.

I have already said much about China, having argued for several years that China’s economy couldn’t possibly continue to expand at the same rate. Leaving aside all the specific arguments, extraordinarily rapid growth in an export-oriented economy requires economic health among its customers. It is nice to imagine expanded domestic demand, but in a country as impoverished as China, increasing demand requires revolutionizing life in the interior. China has tried this many times. It has never worked, and in any case China certainly couldn’t make it work in the time needed. Instead, Beijing is maintaining growth by slashing profit margins on exports. What growth exists is neither what it used to be nor anywhere near as profitable. That sort of growth in Japan undermined financial viability as money was lent to companies to continue exporting and employing people — money that would never be repaid.

It is interesting to recall the extravagant claims about the future of Japan in the 1980s. Awestruck by growth rates, Westerners did not see the hollowing out of the financial system as growth rates were sustained by cutting prices and profits. Japan’s miracle seemed to be eternal. It wasn’t, and neither is China’s. And China has a problem that Japan didn’t: a billion impoverished people. Japan exists, but behaves differently than it did before; the same is happening to China.

Both Europe and China thought about the world in the post-Cold War period similarly. Each believed that geopolitical questions and even questions of domestic politics could be suppressed and sometimes even ignored. They believed this because they both thought they had entered a period of permanent prosperity. 1991-2008 was in fact a period of extraordinary prosperity, one that both Europe and China simply assumed would never end and one whose prosperity would moot geopolitics and politics.

Periods of prosperity, of course, always alternate with periods of austerity, and now history has caught up with Europe and China. Europe, which had wanted union and sovereignty, is confronting the political realities of EU unwillingness to make the fundamental and difficult decisions on what union really meant. For its part, China wanted to have a free market and a communist regime in a region it would dominate economically. Its economic climax has left it with the question of whether the regime can survive in an uncontrolled economy, and what its regional power would look like if it weren’t prosperous.

And the United States has emerged from the post-Cold War period with one towering lesson: However attractive military intervention is, it always looks easier at the beginning than at the end. The greatest military power in the world has the ability to defeat armies. But it is far more difficult to reshape societies in America’s image. A Great Power manages the routine matters of the world not through military intervention, but through manipulating the balance of power. The issue is not that America is in decline. Rather, it is that even with the power the United States had in 2001, it could not impose its political will — even though it had the power to disrupt and destroy regimes — unless it was prepared to commit all of its power and treasure to transforming a country like Afghanistan. And that is a high price to pay for Afghan democracy.

The United States has emerged into the new period with what is still the largest economy in the world with the fewest economic problems of the three pillars of the post-Cold War world. It has also emerged with the greatest military power. But it has emerged far more mature and cautious than it entered the period. There are new phases in history, but not new world orders. Economies rise and fall, there are limits to the greatest military power and a Great Power needs prudence in both lending and invading.

A New Era Begins

Eras unfold in strange ways until you suddenly realize they are over. For example, the Cold War era meandered for decades, during which U.S.-Soviet detentes or the end of the Vietnam War could have seemed to signal the end of the era itself. Now, we are at a point where the post-Cold War model no longer explains the behavior of the world. We are thus entering a new era. I don’t have a good buzzword for the phase we’re entering, since most periods are given a label in hindsight. (The interwar period, for example, got a name only after there was another war to bracket it.) But already there are several defining characteristics to this era we can identify.

First, the United States remains the world’s dominant power in all dimensions. It will act with caution, however, recognizing the crucial difference between pre-eminence and omnipotence.

Second, Europe is returning to its normal condition of multiple competing nation-states. While Germany will dream of a Europe in which it can write the budgets of lesser states, the EU nation-states will look at Cyprus and choose default before losing sovereignty.

Third, Russia is re-emerging. As the European Peninsula fragments, the Russians will do what they always do: fish in muddy waters. Russia is giving preferential terms for natural gas imports to some countries, buying metallurgical facilities in Hungary and Poland, and buying rail terminals in Slovakia. Russia has always been economically dysfunctional yet wielded outsized influence — recall the Cold War. The deals they are making, of which this is a small sample, are not in their economic interests, but they increase Moscow’s political influence substantially.

Fourth, China is becoming self-absorbed in trying to manage its new economic realities. Aligning the Communist Party with lower growth rates is not easy. The Party’s reason for being is prosperity. Without prosperity, it has little to offer beyond a much more authoritarian state.

And fifth, a host of new countries will emerge to supplement China as the world’s low-wage, high-growth epicenter. Latin America, Africa and less-developed parts of Southeast Asia are all emerging as contenders.

Relativity in the Balance of Power

There is a paradox in all of this. While the United States has committed many errors, the fragmentation of Europe and the weakening of China mean the United States emerges more powerful, since power is relative. It was said that the post-Cold War world was America’s time of dominance. I would argue that it was the preface of U.S. dominance. Its two great counterbalances are losing their ability to counter U.S. power because they mistakenly believed that real power was economic power. The United States had combined power — economic, political and military — and that allowed it to maintain its overall power when economic power faltered.

A fragmented Europe has no chance at balancing the United States. And while China is reaching for military power, it will take many years to produce the kind of power that is global, and it can do so only if its economy allows it to. The United States defeated the Soviet Union in the Cold War because of its balanced power. Europe and China defeated themselves because they placed all their chips on economics. And now we enter the new era.

Beyond the Post-Cold War World is republished with permission of Stratfor.”