Currency

By: Marin Katusa

There’s a major shift under way, one the US mainstream media has left largely untouched even though it will send the United States into an economic maelstrom and dramatically reduce the country’s importance in the world: the demise of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

For decades the US dollar has been absolutely dominant in international trade, especially in the oil markets. This role has created immense demand for US dollars, and that international demand constitutes a huge part of the dollar’s valuation. Not only did the global-currency role add massive value to the dollar, it also created an almost endless pool of demand for US Treasuries as countries around the world sought to maintain stores of petrodollars. The availability of all this credit, denominated in a dollar supported by nothing less than the entirety of global trade, enabled the American federal government to borrow without limit and spend with abandon.

The dominance of the dollar gave the United States incredible power and influence around the world… but the times they are a-changing. As the world’s emerging economies gain ever more prominence, the US is losing hold of its position as the world’s superpower. Many on the long list of nations that dislike America are pondering ways to reduce American influence in their affairs. Ditching the dollar is a very good start.

In fact, they are doing more than pondering. Over the past few years China and other emerging powers such as Russia have been quietly making agreements to move away from the US dollar in international trade. Several major oil-producing nations have begun selling oil in currencies other than the dollar, and both the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have issued reports arguing for the need to create a new global reserve currency independent of the dollar.

The supremacy of the dollar is not nearly as solid as most Americans believe it to be. More generally, the United States is not the global superpower it once was. These trends are very much connected, as demonstrated by the world’s response to US sanctions against Iran.

US allies, including much of Europe and parts of Asia, fell into line quickly, reducing imports of Iranian oil. But a good number of Iran’s clients do not feel the need to toe America’s party line, and Iran certainly doesn’t feel any need to take orders from the US. Some countries have objected to America’s sanctions on Iran vocally, adamantly refusing to be ordered around. Others are being more discreet, choosing instead to simply trade with Iran through avenues that get around the sanctions.

It’s ironic. The United States fashioned its Iranian sanctions assuming that oil trades occur in US dollars. That assumption – an echo of the more general assumption that the US dollar will continue to dominate international trade – has given countries unfriendly to the US a great reason to continue their moves away from the dollar: if they don’t trade in dollars, America’s dollar-centric policies carry no weight! It’s a classic backfire: sanctions intended in part to illustrate the US’s continued world supremacy are in fact encouraging countries disillusioned with that very notion to continue their moves away from the US currency, a slow but steady trend that will eat away at its economic power until there is little left.

Let’s delve into both situations – the demise of the dollar’s dominance and the Iranian sanction shortcuts – in more detail.

To Read More CLICK HERE

What do William Lowndes Yancey, Edmund Ruffin, and Geert Wilders have in common? Even though the first two owned black slaves in the 1800s and the last of that trio has spoken out against the spread of Islam across Europe in recent years, no – they’re not all racists.

They’re all secessionists. Or at least wannabe secessionists.

Yancey and Ruffin were known to be part of the “fire-eaters” who devoted themselves to Southern independence as the Northern states sought to undermine the Southern economy by eradicating slavery.

Wilders, who has vehemently opposed the “immigration of Islam” from Muslim countries into Europe, now looks ready to defend The Netherlands, and the North, on a different front …

Over the weekend Wilders refused to engage Brussels in budget talks aimed at austerity. Now the EU faces a political commotion from The Netherlands as it tries to bring the region together and mitigate recession. Wilders has said he wants The Netherlands out of the euro and wants to bring back the Dutch guilder. He’s tired of the constant patchwork responses from EU and Eurozone leaders.

Of course, this is just one guy who doesn’t have the clout to really pull strings at any given moment; but he is loud enough and prominent enough to be heard and seen. And we know how much the status quo hates dissent, no matter where you are.

Yesterday, the ruling Netherlands government fell over disagreement about ongoing Eurozone austerity measures. Hmmm … Timely for Mr. Wilders – he is putting the big question on the table: can the euro survive in its current form?

My view – it doesn’t seem so.

To Continue Reading CLICK HERE

He roller coaster

He got early warning

He got muddy water

He one Mojo filter

He say one and one and one is three

Got to be good looking

Cause he’s so hard to see

Come together right now

Over me

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

Come together, yeah

-The Beatles

It seems the European Central Bankers didn’t read the latest issue of Institutional Investor. Had they perused the pages, they may have stumbled on an acceptable strategy from former Goldman Sachs managing partner slash US Treasury Secretary slash Citigroup chairman, Robert Rubin. In the words of writer Ben Baris, speaking on the subject of restoring the US economy Rubin said, “A potent combination of political will and the legislative agenda must come into alignment and rejuvenate Washington in order to achieve any goals.”

Funny, later in the article Rubin criticized the Europeans for how they were handling their crisis (implying their stop-and-go tactics should be avoided in the US.)

I would have liked to have been sitting with Sir Robert around an infinity edge pool at some Caribbean getaway this weekend when the European Central Bank tore away their metaphorical WWRRD bracelets in protest of added bureaucratic pressure from “above.”

The G-20 met this weekend to approve additional funding of the IMF that could backstop, particularly with respect to Europe, any nation that might come under pressure during a critical period of economic reforms. Member countries were heard to be singing a cappella to The Beatles hit song, Come Together, which explained comments after the meeting that suggested most finance ministers were on board with this move to bolster IMF resources.

That is except for two relevant parties: the US (who did not want to ask Congress for any more money) and the European Central Bank.

The IMF expressly asked the ECB to cut interest rates back further and ready the liquidity spots in hopes of further relieving economic pressure. And the US’s reluctance to probe Congress didn’t stop Treasury Secretary Geithner from laying responsibility on the back of the ECB. Even though the IMF’s stated goal of raising an additional $400+ billion was achieved this weekend, there is plenty of negativity surrounding the ECB’s discretion.

ECB executive board member Joerg Asmussen

“We think we have done our task in the last months by quite a number of standard and non-standard measures we have taken,”

ECB Vice President Vitor Constancio

“The stance of our monetary policy is fully appropriate … It’s appropriate to the situation and the prospects that we (face) right now.”

ECB’s Jens Weidmann

“You cannot solve structural problems in the economy with instruments of the monetary policy.”

“Higher interest rates are also an incentive to restore lost confidence. The common monetary policy must not be used to compensate for shortfalls in reforms.”

The euro is under pressure this morning. [A major slump in German PMI manufacturing – 46.3 vs. expectations of 49.0 – is not helping, especially since recent sentiment numbers out of Germany have been cause for optimism.]

To Read More CLICK HERE

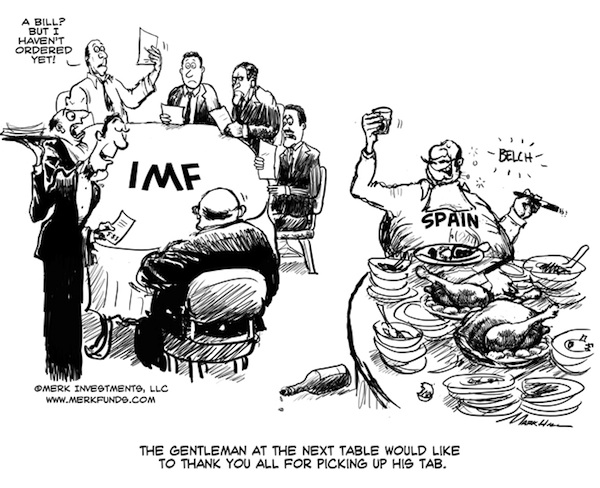

Axel Merk, Merk Funds

If running out of your own money wasn’t bad enough, policy makers are increasingly spending other peoples’ money to bail their country out. At the upcoming G-20 meeting, finance ministers from around the world will contemplate an increase to the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At stake for politicians is whether they can continue to do what they know best – to play politics. In contrast, at stake for investors may be whether currencies will retain their function as a store of value.

One of the major concerns is Spain’s regional government debt. Spain consists of 17 autonomous regions, whose total debt almost doubled in the past three years, due to economic recession and a housing market collapse. In many ways, Spain reflects a microcosm of how the Eurozone as a whole is structured:Let’s highlight Spain, as the country may be the key to understanding how dynamics may play out. Last November, Spaniards voted for change by electing conservative Prime Minister Rajoy, handing him an absolute majority in parliament, displacing the previous, socialist government. The election may cause former British Prime Minister Thatcher to change her view, that socialism is doomed to fail, as ultimately you run out of other people’s money. It doesn’t take a socialist to run out of money. In the case of Spain, if you run out of your own people’s money, there may always be other peoples’ money.

Spanish regions have the power to issue public debt. The central government has little ability to interfere with regional government spending and is prohibited by Spanish law to bailout regional governments.

While regions enjoy high autonomy on spending, the central government retains effective control over regional government revenue.

Spain has its own peripheral problems: the most indebted region, Catalonia, recorded 20.7% debt-to-regional-GDP ratio and 3.6% deficit-to-GDP ratio in 2011. Its 10-year bond yield recently breached 10%, far beyond the yield on 10-year Spanish government bonds, which yield around 6%. In 2011, the total debt of 17 regional governments rose to €140 billion, accounting for 13.1% of Spain’s GDP. This number is up from 6.7% by 2008.

Spanish law forbids the central government from rescuing regional governments (in much the same way that the Maastricht Treaty prohibits bailouts of EU countries). In practice, the central government appears to have implicitly helped Valencia, Spain’s 2nd most indebted region, with a €123 million loan repayment to Deutsche Bank.

More broadly known are Spain’s banking woes. Unlike much of Europe, a housing boom propelled much of Spain’s recent growth, causing Spain’s regional banks, in particular, to become overly exposed to the mortgage sector. Spain’s banks are very dependent on liquidity provided by the European Central Bank (ECB). The recent 3 year long-term refinancing operation (LTRO) by the ECB at first took pressure of the Spanish banking system, but has since been seen more critically, as Spain’s banks may be using the liquidity to buy Spanish government debt, thus increasing inter-dependency and potentially making nationalization of Spanish banks (read: the Spanish government taking on the obligations of its banks) more, rather than less likely.

To Read More CLICK HERE

Ashraf Laidi

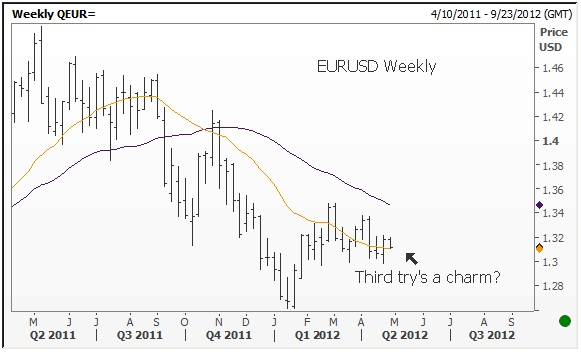

Forced Liquidation or Improved Sentiment?

Recent intermittent bounces in EURUSD in the face of surging Eurozone spreads are said to be reflecting possible liquidation by European banks unloading US assets to relieve an ensuing shortage of US dollars. Other explanations were attributed to the IMF buying Irish and Portuguese bailout tranches during the late European trading hours, taking advantage of cheaper levels (lowest since Feb 15). But as long as traders find no confidence in battling the coordinated efforts of asset-buying central banks and the Fed produces no new dissenters to the ultra low rates til 2014 mantra, risk currencies may be assured to find support.

Spanish government bonds are now the latest victim of bond traders typical one-country assault amid speculation that Spain will be the 4th recipient of a Eurozone bailout. At a time of deepening recession, Spanish authorities have selected education and health sectors for 10 billion in budget cuts. Cuts in these sectors have yet to prove successful or sustainable the he Eurozone. Little surprise that the biggest yield gainers are of nations, which have not yet been bailed outSpain and Italy. Considering that Greece, Ireland and Portugal were each bailed out when their 10-year yields crossed the 7% level, we ought to watch Spanish yields, currently at 5.9%.

The chart below shows how zero purchases from the ECBs Securities Market Programme (SMP) was replaced by the LTRO-1/2 program and Greek Private Sector Initiative deal (PSI), all of which were effective in shorting up risk appetite and the euro at the expense of sovereign yields. Unless the ECB acts with the next dosage of stimulus (LTRO, SMP or swap operations with the Fed, EURUSD is most likely to finally break the $1.2950 floor.

CLICK HERE to Read More