Written by David Einhorn via huffingtonpost.com

A Jelly Donut is a yummy mid-afternoon energy boost.

Two Jelly Donuts are an indulgent breakfast.

Three Jelly Donuts may induce a tummy ache.

Six Jelly Donuts — that’s an eating disorder.

Twelve Jelly Donuts is fraternity pledge hazing.

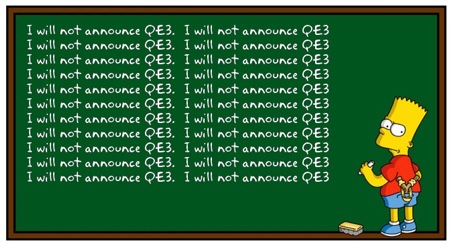

My point is that you can have too much of a good thing and overdoses are destructive. Chairman Bernanke is presently force-feeding us what seems like the 36th Jelly Donut of easy money and wondering why it isn’t giving us energy or making us feel better. Instead of a robust recovery, the economy continues to be sluggish. Last year, when asked why his measures weren’t working, he suggested it was “bad luck.”

I don’t think luck has anything to do with it. The blame lies in his misunderstanding of human nature. The textbooks presume that easier money will always result in a stronger economy, but that’s a bad assumption. Here is a good example of how a real family responds to monetary policy.

Consider my neighbors, Homer, Marge, and their three adult children, Bart, Lisa and Maggie. Homer has retired from the nuclear plant, and he and Marge live off savings and Homer’s pension. Bart is in a bit of trouble with too much credit card debt and an underwater mortgage. Lisa has been putting away her salary and has enough for a downpayment on her first home. Maggie owns her own business and is ready to expand.

When interest rates are high, Homer and Marge park their savings in CDs or Money Market accounts and get a decent return. There is no incentive for them to take much risk with their money. Bart gets into trouble very quickly and defaults on his loans. Lisa decides she can’t afford a mortgage until rates fall. And Maggie, who’s been helping out Bart with some of his expenses, believes that she’d make money if she grew the business, but possibly not enough to service the debt she’d be undertaking.

When interest rates are low, everything changes. Homer and Marge are getting only a little interest on their savings, and are struggling to live off Homer’s pension. They need to rethink their finances. Bart can manage to keep up the minimum payments on his credit cards and stay in his house. Lisa can get a cheap mortgage, and Maggie doesn’t need to make such optimistic assumptions in order to expand her business.

Everyone agrees that low interest rates are a good way to stimulate a stalled economy. The Fed takes this logic a step further. It believes that if low interest rates are good, then zero-interest rates must be even better. As a brief emergency measure, such drastic behavior is reasonable and can even be necessary. In 2008, Chairman Bernanke had near unanimous support for his decision to drop rates to near zero. At the peak of the crisis, it made sense. But that was four long years and many jelly donuts ago. In the 2012 economy, a zero rate policy not only adds no benefit, it’s actually harmful. Just ask the Simpsons.

When Homer was approaching 65, he and Marge met with a financial planner to figure out if they had enough money saved for retirement. They assumed they’d live to be 90, and could count on receiving a fixed amount from Homer’s pension and social security checks. Marge, the cautious one, has not forgotten that stock market meltdown better known as the bursting of the tech bubble. She didn’t want to take any investment risk and was content to have just enough for regular haircuts for herself, a bowling and beer budget for Homer, and visits with the children. They were told that, with nominal interest rates at 3%, they could safely retire with $200,000.

“What happens if interest rates go to zero and stay there?” Marge asked the advisor.

“You mean indefinitely? If you weren’t willing to start taking investment risk, you’d need 50% more in savings, or $300,000. But why would you ask such a silly question?” asked the advisor.

To which Marge replied, “Well, we were thinking about moving to Japan…”

Homer and Marge aren’t the only ones doing this sort of math. Every single day for the next 19 years, more than 10,000 Baby Boomers will turn 65. Those who started saving for retirement 15 years ago are suddenly finding themselves with insufficient savings to do so.

Some will stay in the work force longer, some will drastically reduce their spending, and some will do both. In a recent survey, 20% of U.S. workers say they have postponed their planned retirement age at least once during the last year. And those who have already retired have fewer options. Returning to the workforce could be challenging. David Rosenberg points out that the workforce for those 55 and older has expanded by 4 million since the start of the recession, and they are returning to the workforce at lower wages. Even more challenging is trying to find safe investments that generate a decent yield.

To Read More CLICK HERE