Perhaps you saw my comments last week BEFORE the European Central Bank surprised the markets with an interest rate cut. After seeing the inflation data come in weak, I asked:

Does that mean another LTRO (Long-Term Refinancing Operation) is right around the corner, the same corner around which the eurozone economy will supposedly turn?

Doubtful, at this stage. But don’t abandon the idea completely. If things get nasty, the European Central Bank will need to do something to help re-recapitalize a financial system built on crummy collateral.

The ECB is now moving to counteract, according to Mario Draghi’s post-meeting press conference, a “prolonged period of low inflation.”

And another ECB guy, Ewald Nowotny, is singing the same tune. Nowotny sees low inflation for some time. He also thinks stagflation is a greater risk than inflation. And another ECB guy, Jorg Asmussen, is so cautious he wouldn’t rule out negative interest rates.

Does any of this really surprise us?

If it does, it shouldn’t.

Let me offer you part of an idea we shared with our Global Investor members two weeks ago, titled:Neuroscience warns of financial market risks

Let us refer you to this Wired.co.uk article that summarizes a something else that neuroscientists are working on – it could explain, and even help anticipate, what would generate a coming collapse in risk appetite and risk markets.

“According to Lionel Barnett, lead author on the paper, they found the fact that all the elements “causally influence each other” to be of most importance. It means we must first identify all the parts of a system, then assess the relationship between individual nodes and then their causal effect on the whole. In doing so, we can find out when the fate of a node is dependant on its own behaviour because it behaves so differently from the others, and when its fate is dependant on all other nodes.

“”The dynamics of complex systems — like the brain and the economy — depend on how their elements causally influence each other; in other words, how information flows between them,” said Barnett.”

Now let us try our best to make this relevant …

Based on our shallow, yet appreciative, understanding of behavioral finance, financial markets are driven largely by sentiment. Herd mentality, for example, is one way of categorizing such sentiment.

Hence, if there is something to trigger an abrupt change in sentiment, a feedback loop, a chain reaction, can occur.

…

Back to the Wired article again:

“Using supercomputers at the Charles Sturt University in Australia, the team found that one measure called “global transfer entropy flow” reached a peak, repeatedly, “on the disordered side of the transition — just before the tipping point”.

“It’s the density of the information flow that anticipates the tipping point — “all other measures peak strictly at the tipping point itself” explained Seth.”

Now based on where our discussion is pointing, it seems counterintuitive to suggest the information flow right now is in a state of disorder and, after the tipping point is reached will converge into a state of order. After all, if the tipping point is to unleash a period of market turmoil, does that not imply disorder and chaos?

Actually, it does not if you’re thinking like a neuroscientist or Nassim Taleb. You might remember our recent review of Mr. Taleb’s new must-read book Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder.

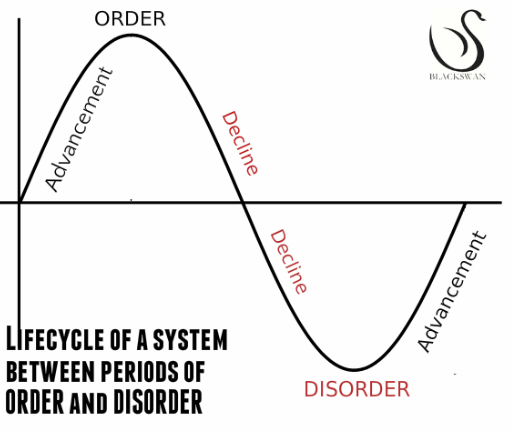

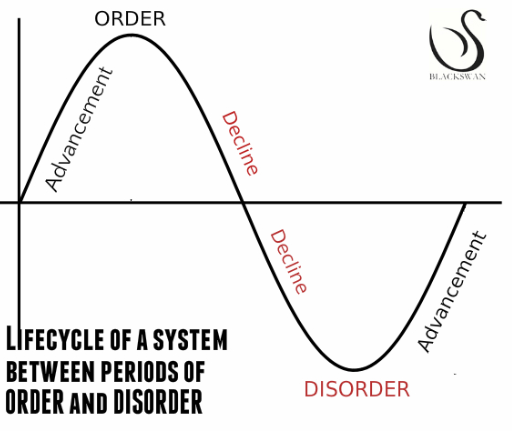

So what we should do is try to visualize the life cycle of a system’s advancement and decline between states of order and disorder. Here’s a diagram we’ve produced that we think generally applies:

I think the diagram is relatively clear. Now let’s assume the system in question is financial markets.

The financial crisis brought disorder. And that disorder bred advancement in financial markets. But amidst this advancement grew up initiatives aimed at producing order, e.g. extraordinary monetary policy.

Our central banks have built a highly-ordered financial system. And because of how the elements in such a complex financial system causally influence one another, our central banks cannot extract a vital element of the system — QE — without causing financial market instability.

It is why we’re constantly suffering through people like Larry Summers, confounded in their smug intellectualism (at best), bumbling on about keeping the lights on during a power outage. He of course equates power outage with economic/financial crisis andlights with fiscal/monetary stimulus.

It’s his analogy to why it’s so important to “contain the financial system.”

And though he did throw out a token criticism of monetary policy at the end — low rates are an inhibitor of economic growth — his overall implication is one that requires a fiscal policy to more closely manage the economy so the lights don’t go off.

But monetary policy, in an effort to enable a dysfunctional fiscal policy, has effectively commandeered control of the light-switch. But because they’ve sought stability in the financial system first and foremost. They sought merely, albeit actively, to restore sentiment instead of letting the economy clear out excesses and malinvestment.

These problems linger. And these problems continue to push down on the light-switch. The only thing holding up the light-switch is indeed extraordinary accommodation.

The million dollar question: can more accommodation, whether monetary or fiscal, in an effort to contain the financial system, eliminate the pressures pushing down on the light-switch?

As Mr. Summers mentioned, we’re four to five years down the road now. I ask: why hasn’t accommodation worked yet? And no, Paul Krugman, I’m not asking you because I already know your answer.

Are we closer to financial system decline — the collapse of the highly-ordered system — than most are willing to believe? If so, maybe we should look at the good that could come from disorder in our financial system …

After all, we’d see the deterioration of “a chronic inhibitor of economic growth”, that which is “holding our economies back from achieving their true potential.”

-JR Crooks