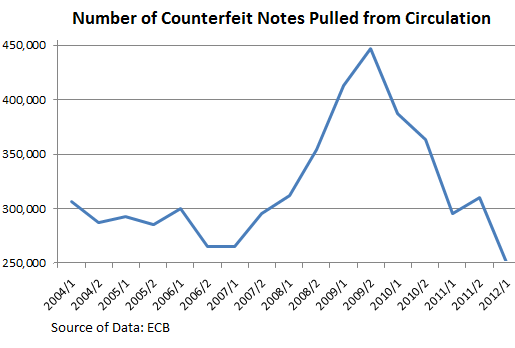

After a fairly steady period through 2006, euro counterfeiting jumped 70% to its peak in the second quarter of 2009. Alas, following on the heels of the financial crisis, the Eurozone debt crisis began to gnaw on periphery countries, and counterfeiters lost confidence along with the rest of the financial markets. By the first half of 2012, counterfeiting had crashed 44%. And not much but thin Alpine air appears to be underneath it.

The fact that counterfeiters are throwing in the towel—worried perhaps that they’ll get stuck with high-risk but unsalable merchandise—is bad enough for Europhiles. But now we see an increasingly clear demarcation of the Eurozone into two separate parts, though not entirely along the lines of North and South often envisioned.

On one side of the line are countries whose governments can borrow at negative yields, that is, where investors agree to lend money to them at a guaranteed loss, however absurd that might have seemed not long ago. That club includes Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium (!); in the secondary markets, Finnish and Austrian government debt has seen negative yields. Eurozone neighbors Denmark and Switzerland also dipped into negative yields. Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP) at work.

On the other side are countries whose governments have lost access to the financial markets or are in the process of losing access. The largest two in that group are Spain and Italy.