Stocks & Equities

For the first time since the recovery began, Warren Buffett’s favorite valuation metric has breached the 100% level. That, of course, is the Wilshire 5,000 total market cap index relative to GNP. See the chart below for historical reference.

……read more HERE

ART CASHIN: “A Dormant US Inflation Indicator Just Spiked, And It’s Got Me Thinking Of Weimar And Zimbabwe”

In an interview with King World News Veteran trader Art Cashin makes it clear he has been more concerned about the threat of inflation in the U.S. than most analysts. From that interview King World News:

“That having been said, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis puts out what is called the ‘Monetary Stock.’ It is the ‘raw material’ of the money supply, and it has been dormant throughout the year.

The report for the first part of this year suddenly spiked higher, and it’s something that I’m going to keep a very close look at. It may be, and there is some seasonality, but I think people need to begin watching the money supply, particularly the M2, and see if that starts to accelerate…

If the velocity of money begins to accelerate and M2 begins to move up, then you will begin to hear people talking about or at least worrying about inflation again…”

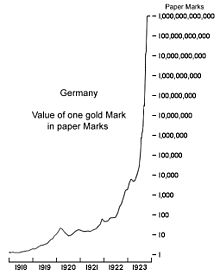

Cashin notes that this isn’t just theory, as we’ve not only seen it before in history, most people know of the most recent notorious experiences: Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe.

“Somebody once asked a famous literary character (who lived through the Weimar hyperinflation) how did he go broke? He said, ‘Slowly and then suddenly.’ The Weimar Republic saw inflation develop very slowly, and then suddenly. Once it developed it was almost like Zimbabwe except it was in a major nation, and destroyed the moral values of a whole civilization and basically led to the underpinnings of World War II.”

“Somebody once asked a famous literary character (who lived through the Weimar hyperinflation) how did he go broke? He said, ‘Slowly and then suddenly.’ The Weimar Republic saw inflation develop very slowly, and then suddenly. Once it developed it was almost like Zimbabwe except it was in a major nation, and destroyed the moral values of a whole civilization and basically led to the underpinnings of World War II.”

….read more at KingWorldNews HERE

With the non-inflation-adjusted Dow is trading 1% below its all-time record high, today’s chart provides some long-term perspective with a chart of the inflation-adjusted Dow since 1900. Of interest is that the inflation-adjusted Dow has traded within the confines of an extremely long-term upward sloping trend channel over the past 113 years. It is also of interest that the secular bear market that concluded in the early 1980s was almost as severe as the one that concluded in the early 1930s. Also, while the market action from the inflation-adjusted record high of 1999 to the financial crisis lows of 2009 was severe, the magnitude of this decline was much less than what occurred with the bear markets that concluded in the early 1930s and early 1980s. More recently, the Dow has retraced most of the financial crisis bear market though the inflation-adjusted Dow currently trades 10.6% off its 1999 record high. While the inflation-adjusted Dow is not quite as near record highs as is the non-inflation-adjusted Dow, the post-financial crisis rally would have to be considered a rather dramatic turn of events — inflation-adjusted or not.

Quote of the Day

“If you want to succeed you should strike out on new paths, rather than travel the worn paths of accepted success.” – John D. Rockefeller

Events of the Day

February 13, 2013 – Ash Wednesday

February 14, 2013 – Valentine’s Day

February 17, 2013 – NBA All-Star Game – Daytona 500 – Academy Awards

February 18, 2013 – President’s Day – Washington’s Birthday (observed)

February 24, 2013 – Daytona 500 – Academy Awards

Stocks of the Day

— Find out which stocks investors are focused on with the most active stocks today.

— Which stocks are making big money? Find out with the biggest stock gainers today.

— What are the largest companies? Find out with the largest companies by market cap.

— Which stocks are the biggest dividend payers? Find out with the highest dividend paying stocks.

— You can also quickly review the performance, dividend yield and market capitalization for each of the Dow Jones Industrial Average Companies as well as for each of the S&P 500 Companies.

To subscribe to the FREE ChartoftheDay go HERE

Notes:

Where’s the Dow headed? The answer may surprise you. Find out right now with the exclusive & Barron’s recommended charts of Chart of the Day Plus.

Everywhere we look, investors suddenly see nothing but blue skies, plain sailing ahead. Their change of heart makes us nervous.

New York’s S&P index is back where it stood in July 2007 – right before the global credit crunch first bit, eating more than half the stock market’s value inside 2 years…

Japan’s Nikkei index has jumped by one third since mid-Nov., thanks to export companies getting a 20% drop in the Yen – the currency’s fastest drop since right before the Asian Crisis of 1997…

And here in the UK – where the FTSE-100 stock index just enjoyed its strongest January since 1989, when house prices then suffered their biggest post-war drop – average house prices are rising year-on-year, even as the economy shrinks…

The common factor? Zero interest rates and money creation on a scale never tried outside Weimar Germany or Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. Only the Eurozone has stood aside so far, and even then only a little. And yet gold and silver – the most sensitive assets to money inflation – are worse than becalmed.

Daily swings in the silver price haven’t been this small since spring 2007. Volatility in the gold price has only been lower than Thursday this week on 15 days since the doldrums of mid-2005. Back then the Dollar also steadied and rose after multi-year falls. Industrial commodities outperfomed ‘safe haven’ gold too – a pattern echoed here in early 2013 by the surge in the price of useful platinum over industrially ‘useless’ gold.

Perhaps the flat-lining points to better times ahead. Gold after all is where retained capital hides when things are bad – a store of value to weather the storm. Or it may signal itchy feet in the ‘hot money’ crowd, now moving back into stocks and shares instead. But we can’t shake the feeling that something awful is afoot. Gold and silver aren’t making headlines today. Just like they didn’t before the financial crisis began.

“Japan is on an unsustainable path of a strong Yen and deflation,” wrote Andy Xie – once of Morgan Stanley, now director of Rosetta Stone Advisors – back in March 2012.

“The unprofitability of Japan’s major exporters and emerging trade deficits suggest that the end of this path is in sight. The transition from a strong to weak Yen will likely be abrupt, involving a sudden and big devaluation of 30 to 40 percent.”

Already since the Abe-nomic revolution announced in November the Yen has dropped more than 20% versus the Dollar. But “there is plenty of liquidity still parked in the Yen,” Xie noted this week. Quite apart from the shock to America’s trade deficitwhich surging shale-oil supplies deliver, “The Dollar bull is due less to the United States’ strengths than the weaknesses in other major economies,” he adds. And reviewing the last two major counter-trend rallies in the Dollar’s otherwise permanent decline, “The first dollar bull market in the 1980s triggered the Latin American debt crisis, the second the Asian Financial Crisis. Neither was a coincidence.”

Neither of those crises coincided with a bull market in gold or silver. Savers worldwide chose Dollars instead as the hottest emerging-market investments collapsed. But then neither of those slumps saw emerging-market central banks so stuffed with money, nor gold and silver so freely available to their citizens.

China’s gold imports almost doubled last year, with net demand overtaking India for the world’s #1 spot at last. This week the People’s Bank of China pumped a record CNY860bn into the money markets ($140bn), crashing Shanghai’s interbank interest rates by almost the whole one-percent point they had earlier spiked ahead of the coming New Year’s long holidays.

The disparity, meantime, between the doldrums in precious metals and the bull market in Dollar-Yen trading can be seen by glancing at the US derivatives market. Yesterday the CME Group cut margin requirements on gold and silver futures. It raised the margin payments needed to play the Yen‘s [lightning] drop. One of those moves is likely bullish, short-term. But you’d to borrow money to choose.

Western pension funds are meanwhile pulling out of commodities, and just as liquidity floods back into the market. Both the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Timesreport how big institutions have quite hard assets “after finding they did little to protect their portfolios against inflation risk and the unpredictable returns of stocks.” One of the biggest commodity hedge funds, Clive Capital, has shrunk from $5 billion under management two years ago to less than $2bn today. And yet European banks – the major source of credit to commodities traders – are now reviving their commodities lending.

“The sector came close to panic 18 months ago,” says the FT. But now “The banks want to be again my best friend,” says a Swiss executive. “Funding concerns have now substantially dissipated,” says SocGen’s head of natural resources and energy finance, Federico Turegano.

There’s plenty of money around to borrow, in short. Whether in Chinese banking, currency betting or commodities trading, where there was very little at all, suddenly it’s all turned up at once. Which is just how trouble arrives. All that central-bank liquidity and quantitative easing have so far left consumer-price inflation unmoved, too.

“We can lament all we want, but ultimately, we are observers rather than instigators. We can be actors when it comes to our own wealth, seeking to protect it from the fallout of currency wars. We believe the best place to fight a currency war might be in the currency market itself, as there may be a direct translation from what we call the mania of policy makers into the currency markets. It’s not a zero-sum game, as different central banks print different amounts of money (that is, if one calls central bank balance sheet expansion money “printing,” even if no real currency is printed, but central banks purchase assets with fiat currency created on a keyboard). Equities may also rise when enough money is printed causing all asset prices to float higher, but one also takes on the “noise” of the equity markets: When no leverage is employed, equity markets are substantially more volatile than the currency markets.

“We can lament all we want, but ultimately, we are observers rather than instigators. We can be actors when it comes to our own wealth, seeking to protect it from the fallout of currency wars. We believe the best place to fight a currency war might be in the currency market itself, as there may be a direct translation from what we call the mania of policy makers into the currency markets. It’s not a zero-sum game, as different central banks print different amounts of money (that is, if one calls central bank balance sheet expansion money “printing,” even if no real currency is printed, but central banks purchase assets with fiat currency created on a keyboard). Equities may also rise when enough money is printed causing all asset prices to float higher, but one also takes on the “noise” of the equity markets: When no leverage is employed, equity markets are substantially more volatile than the currency markets.

Some call currency markets too difficult to understand. We happen to think that ten major currencies are much easier to understand than thousands of stocks. But nobody said it’s easy.

Calling it a race to the bottom does not give credit to what we believe are dramatically different cultures across the world. Gold may be the winner long-term, but for those who don’t have all their assets in gold, the question remains how to diversify beyond what we call the ultimate hard currency. To potentially profit from currency wars, you need to project your view of what policy makers may be up to onto the currency space. And if there is one good thing to be said about our policy makers, it is that they may be rather predictable”

Currency wars are evil

Real people may die when countries engage in “currency wars.” Countries debasing their currencies risk, amongst others:

- Loss of competitiveness

- Social unrest

- War

We discuss not only why we believe currency wars are evil, but also what investors may be able to do about them.

Loss of competitiveness

The illusory benefit of a weaker currency is to boost corporate earnings as companies increase their exports. That may well be true for the next quarterly earnings report, but ignores that their competitive position may be weakening. The clearest evidence of this is the increased vulnerability to takeovers from abroad. As the value of the U.S. dollar has been eroding, for example, Chinese companies are increasingly buying U.S. assets. The U.S. is selling its family silver in an effort to support consumption.

Importantly, when a country subsidizes one’s exports with an artificially weak currency, businesses lack an incentive to innovate. Japan is the best example: Japan’s problem is not that of a weak currency, but a lack of innovation. By weakening the yen, companies are given a free ride, taking an incentive away to engage in reform. Advanced economies, in our humble opinion, cannot compete on price, but must compete on value. European companies have long learned this, as there are rather few low-end consumer goods being exported from Germany. The Chinese have also heeded this lesson, allowing low-end industries to fail and relocate to Vietnam or other lower cost countries: China is rapidly moving up the value chain in goods and services produced. Incidentally, Vietnam has repeatedly engaged in currency devaluation, as the country mostly competes on price; in the absence of a strong consumer recovery in the U.S., we see further currency debasements in Vietnam.

In summary, market pressure to innovate is the most powerful motivation. Governments subsidizing ailing industries through currency debasement do long-term harm to their economies.

Social unrest

Currency debasement is not just bad for the corporate world: it’s particularly painful for citizens. Just ask citizens of Venezuela where the government just announced a 32% devaluation in the bolívar’s official exchange rate to the dollar. An overnight move of that magnitude is immediately noticeable, as are the negative effects on consumers, whereas gradual debasement in currencies of advanced economies are less noticeable, but ultimately have the same effect. The natural consequence of currency debasement is inflation, i.e., loss of real purchasing power; the two forces meet at the gas pump: As a currency loses value, commodities — all else equal — become pricier when valued in that currency.

Stagnant real wages in the U.S. over the past decade may in large part be attributed to the gradual debasement of the greenback, courtesy of fiscal and monetary policy. Folks whose real wages didn’t go anywhere for a decade feel cheated and are more likely to vote for populist politicians promising change. Currency debasement fosters growing income and wealth inequality and diverging political reactions, e.g., the Tea Party movement on the political right and the Occupy Wall Street movement on the political left. The rise of populism can be seen in the rise of Twitter: We sometimes quip that politicians that can distill their political message into a tweet have a better chance of being elected these days. Except that we are wrong: It’s not a joke.

In the Middle East, similar trends cause revolutions. People can be suppressed for a long time, but if they can’t feed themselves, they revolt. In the U.S., we are told food and energy is to be excluded from measuring inflation, as our economy is less and less dependent on food and energy (although curious that a record number of Americans used food stamps last year). However, in countries where large segments of the population cannot earn enough to feed themselves, currency debasement contributes to revolutions, not just the rise of populism.

War

For those that believe currency debasement is the appropriate way to escape a depression, keep in mind that the Great Depression provided a transition to World War II. Currency Wars fought in the first half of the 20th century tended to be a result of fiscal policy. For example, in 1925, the U.K. returned to the gold standard at pre World-War-I levels, although the U.K. could ill afford it. In 1931, Britain was forced to depart from the gold standard again. Japan suspended the gold standard in 1917, returned to it in early 1930, only to depart from it again in late 1931. In 1934, the U.S. dollar was devalued by 40% when an ounce of gold was officially priced at $35 an ounce, up from $20.67 an ounce. Exchange rates caught up with reality.

In today’s world, where major countries have free-floating exchange rates, monetary policies appear to be more pro-active rather than reactive. Either way, underlying fiscal or monetary policy have a profound impact on currency values, both in real (purchasing power) and relative (exchange rate) terms. Given unprecedented debt and deficit levels on the fiscal side, and aggressive central bank balance sheet expansion on the monetary side, we believe the term “currency war” is more than appropriate.

When told by Fed Chairman Bernanke that the gold standard prolonged the Great Depression, many feel as if monetary activism were a blessing rather than a curse. In our assessment, Ivory Tower economists are particularly apt at confusing cause and effect. The root causes of a depression are excessive debt, not currencies that are too strong. Currency debasement and expansionary monetary policies are attempts to socialize such debt, bailing out those that have taken on irresponsible debt burdens. But because governments tend to be in the group of those taking on excessive debt burdens, we are made to believe that such policy is for the greater good.

We respectfully disagree: Currency wars destroy wealth. Currency wars have a disproportionate impact on the poor, as they don’t hold assets whose value is inflated in nominal terms and that could buffer some of the fallout. Central banks don’t cause real wars. But monetary policy has a profound impact on the social fabric. Abstract theories about how aggressive monetary action are the remedy to depressions ignores the heavy social toll currency wars have on people. For those that argue that the social toll of a depression is greater, we respond that the best short-term policy to address economic ills is a good long-term policy. We cannot see how currency wars can be good long-term policy.

What to do about Currency Wars

We can lament all we want, but ultimately, we are observers rather than instigators. We can be actors when it comes to our own wealth, seeking to protect it from the fallout of currency wars. We believe the best place to fight a currency war might be in the currency market itself, as there may be a direct translation from what we call the mania of policy makers into the currency markets. It’s not a zero-sum game, as different central banks print different amounts of money (that is, if one calls central bank balance sheet expansion money “printing,” even if no real currency is printed, but central banks purchase assets with fiat currency created on a keyboard). Equities may also rise when enough money is printed causing all asset prices to float higher, but one also takes on the “noise” of the equity markets: When no leverage is employed, equity markets are substantially more volatile than the currency markets.

Some call currency markets too difficult to understand. We happen to think that ten major currencies are much easier to understand than thousands of stocks. But nobody said it’s easy.

Calling it a race to the bottom does not give credit to what we believe are dramatically different cultures across the world. Gold may be the winner long-term, but for those who don’t have all their assets in gold, the question remains how to diversify beyond what we call the ultimate hard currency. To potentially profit from currency wars, you need to project your view of what policy makers may be up to onto the currency space. And if there is one good thing to be said about our policy makers, it is that they may be rather predictable.

Axel Merk the president and chief investment officer of Merk Investments, the authority on currencies, and manager of Merk Funds, a suite of no-load currency mutual funds that typically do not apply leverage.

.