Timing & trends

The behavior of markets (and of entire societies) depends on what everyone knows that everyone knows. Make sense? It didn’t to me, either, until Ben Hunt walked me through an example or two of the Common Knowledge Game in the piece you’re about to read.

Ben says the question he is asked most is “When?” When will this market break? When – to use Ben’s term – will the “Narrative of Central Bank Omnipotence” fail? He doesn’t so much answer the question as explain why he can’t answer it. But he doesn’t leave us empty-handed. In fact, Ben’s explanations of market behavior in terms of the narratives in which we all participate and thegames we all play, are among the most useful tools I have for surviving and thriving out here in unexplored and increasingly treacherous territory.

In other words, it may not be so important to know exactly when a major market narrative will fail (though I wouldn’t mind having a working crystal ball) as it is to know how and why it might fail. That way, we have some chance of detecting incipient signs of failure.

I find it fascinating that so much of market behavior happens silently, right inside our skulls – billions of brains, each working overtime to suss out what the rest might be thinking of doing. The “power of the crowd watching the crowd” is the “most potent behavioral force in human society,” says Ben – but the power wielded by those who can watch the crowd watching the crowd is more potent yet, because their perspective on the Common Knowledge Game lets them ask how the game may be about to change.

But what does it take for “what everyone knows that everyone knows” to shift, or even to flip, and for new common knowledge to assert itself and become entrenched? “Fortunately for us,” says Ben, “game theory provides exactly the right tool kit to unpack socially driven dynamic processes.” So let’s get to unpacking!

Ben confesses that there is “a fly in this glorious ointment” of gamesmanship, and that is the potential for major political shocks. Where, he asks, should we look for “a political shock that would be big enough to challenge the common knowledge that Central Banks are large and in charge, capable of bailing us out no matter what?”

I won’t tell you his answer (hint: it’s not Ukraine), I’ll make you dig for it; but on the way you’re going to unearth some real treasure.

Life is busy. We are getting ready to fly to Italy and then find a train to Tuscany and cars to Trequanda. I have dinner with Steve Cucchiara in Rome Friday night, then get up and meet George Gilder, who will be flying in from Boston and spending a week or so with us. We will both spend our days working on new books (although I might take a day to visit Sienna again). Other friends will be dropping by for periods of time. Dylan Grice will show up at some point next week, as will David Tice [of Prudent Bear fame] and Cliff Draughn from Excelsia in Savannah). And others! It will make for fun dinners.

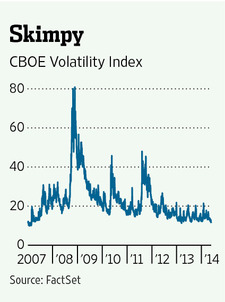

I do somewhat pay attention to the markets and just shake my head in amazement. Who would have guessed an all-time S&P high of 1905 and 2.5% on the ten-year bond? REALLY? And as Doug Kass pointed out this morning, the VIX is back down to 2007 levels! But this next chart, sent to me by Meb Faber, is not so much ominous as just head-shaking funny. Dear gods, we humans have such short term memories. We always seem to believe it’s different this time.

Sell in May and go away? Not so far this May! Maybe we see a swoon in June? If this market action does not make you nervous, then you’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din.

This weekend’s Thoughts from the Frontline will come to you from Rome, but it will take us to China, a place that is even harder to figure than Italy! Have a great rest of the week.

Your wondering how I can lose weight in Italy analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

JohnMauldin@2000wave.com

“When Does the Story Break?”

By Ben Hunt, Ph.D.

Epsilon Theory

May 25, 2014

Until an hour before the Devil fell, God thought him beautiful in Heaven.

– Arthur Miller, “The Crucible”It’s always about timing. If it’s too soon, no one understands. If it’s too late, everyone’s forgotten.

– Anna WintourSaint Laurent has excellent taste. The more he copies me, the better taste he displays.

– Coco ChanelBeauty, to me, is about being comfortable in your own skin. That, or a kick-ass red lipstick.

– Gwyneth Paltrow

For, dear me, why abandon a belief Merely because it ceases to be true? Cling to it long enough, and not a doubt It will turn true again, for so it goes. Most of the change we think we see in life Is due to truths being in and out of favor.

–Robert Frost, “The Black Cottage”Lord I am so tired

How long can this go on?

– Devo, “Working in a Coal Mine”

He can’t think without his hat.

– Samuel Beckett, “Waiting for Godot”

Perhaps the most irrational fashion act of all was the male habit for 150 years of wearing wigs. Samuel Pepys, as with so many things, was in the vanguard, noting with some apprehension the purchase of a wig in 1663 when wigs were not yet common. It was such a novelty that he feared people would laugh at him in church; he was greatly relieved, and a little proud, to find that they did not. He also worried, not unreasonably, that the hair of wigs might come from plague victims. Perhaps nothing says more about the power of fashion than that Pepys continued wearing wigs even while wondering if they might kill him.

– Bill Bryson, “At Home: A Short History of Private Life”

The most common question I get from Epsilon Theory readers is when. When does the market break? When will the Narrative of Central Bank Omnipotence fail? To quote the immortal words of Devo, how long can this go on? Implicit (and sometimes explicit) in these questions is the belief that this – whatever this is – simply can’t go on much longer, that there is some natural law being violated in today’s markets that in the not-so-distant future will visit some terrible retribution on those who continue to flout it. There has never been a more unloved bull market or a more mistrusted stock market high.

It’s a lack of love and a lack of trust that I share. I believe that public markets today are essentially hollow, as what passes for volume and liquidity is primarily machines talking to other machines for portfolio “positioning” or ephemeral arbitrage rather than the human expression of a desire to own a fractional ownership share of a real-world company. I believe that today’s public market price levels primarily reflect the greatest monetary policy accommodation in human history rather than the real-world prospects of real-world companies. I believe that the political risks to both capital market structure and international trade (which are the twin engines of global growth, period, end of story) have not been this great since the 1930’s. Simply put, I believe we are being played like fiddles.

That does NOT mean, however, that I think anything has to change next week … or next month … or next year … or next decade. The human animal is a social animal in the biological sense, and as such we are cognitively evolved to maintain our beliefs and behaviors far beyond what is “true” in an objective sense. This is, in fact, the core argument of Epsilon Theory, that there is no such thing as Truth with a capital T when it comes to the institutions and the social organizations that we create. There’s nothing more “natural” about our market behaviors than there is around, say, our fashion behaviors … the way we wear our clothes or the way we cut our hair. For 150 years everyone knew that everyone knew that gentlemen wore wigs. This was the dominant common knowledge of its day in the fashion world, absolutely no different in any way, shape or form than the dominant common knowledge of today in the investing world … everyone know s that everyone knows that it’s central bank policy that determines market outcomes. And this market common knowledge could last for 150 years, too.

I’m not saying that a precipitous change in market beliefs and behaviors is impossible. I’m saying that it’s not inevitable. I’m saying that it’s NOT just a matter of when. I’m saying that understanding the timing of change in market behaviors is very similar to understanding the timing of change in fashion behaviors, because both are social constructions based on the Common Knowledge Game. It’s no accident that the most popular way to relate that game is the story of the Emperor’s New Clothes.

Here’s a photograph Margaret Bourke-White took of the Garment District in 1930. Every single person on the street is wearing a hat. How did THAT behavior change over time? How did the common knowledge that All Men Wear Hats, or wigs or whatever, change? Does it happen all at once? Smoothly over time? In fits and starts? Who or what sparks this sort of change and how do we know? To use a five dollar phrase, what is the dynamic process that underpins the timing of change in socially-constructed behaviors, whether that behavior is in the investing world or the fashion world?

Fortunately for us, game theory provides exactly the right tool kit to unpack socially driven dynamic processes. To start this exploration, we need to return to the classic thought experiment of the Common Knowledge Game – The Island of the Green-Eyed Tribe.

On the Island of the Green-Eyed Tribe, blue eyes are taboo. If you have blue eyes you must get in your canoe and leave the island the next morning.

On the Island of the Green-Eyed Tribe, blue eyes are taboo. If you have blue eyes you must get in your canoe and leave the island the next morning.

But there are no mirrors or reflective surfaces on the island, so you don’t know the color of your own eyes. It is also taboo to talk or otherwise communicate with each other about blue eyes, so when you see a fellow tribesman with blue eyes, you say nothing. As a result, even though everyone knows there are blue-eyed tribesmen, no one has ever left the island for this taboo.

A Missionary comes to the island and announces to everyone, “At least one of you has blue eyes.”

What happens?

Let’s take the trivial case of only one tribesman having blue eyes. He has seen everyone else’s eyes, and he knows that everyone else has green eyes. Immediately after the Missionary’s statement this poor fellow realizes, “Oh, no! I must be the one with blue eyes.” So the next morning he gets in his canoe and leaves the island.

But now let’s take the case of two tribesmen having blue eyes. The two blue-eyed tribesmen have seen each other, so each thinks, “Whew! That guy has blue eyes, so he must be the one that the Missionary is talking about.” But because neither blue-eyed tribesman believes that he has blue eyes himself, neither gets in his canoe the next morning and leaves the island. The next day, then, each is very surprised to see the other fellow still on the island, at which point each thinks, “Wait a second … if he didn’t leave the island, it must mean that he saw someone else with blue eyes. And since I know that everyone else has green eyes, that means … oh, no! I must have blue eyes, too.” So on the morning of the second day, both blue-eyed tribesmen get in their canoes and leave the island.

The generalized answer to the question of “what happens?” is that for any n tribesmen with blue eyes, they all leave simultaneously on the nth morning after the Missionary’s statement. Note that no one forces the blue-eyed tribesmen to leave the island. They leave voluntarily once public knowledge is inserted into the informational structure of the tribal taboo system, which is the hallmark of an equilibrium shift in any game. Given the tribal taboo system (the rules of the game) and its pre-Missionary informational structure, new information from the Missionary causes the players to update their assessments of where they stand within the informational structure and choose to move to a new equilibrium outcome.

Before the Missionary arrives, the Island is a pristine example of perfect private information. Everyone knows the eye color of everyone else, but that knowledge is locked up inside each tribesman’s own head, never to be made public. The Missionary does NOT turn private information into public information. He does not say, for example, that Tribesman Jones and Tribesman Smith have blue eyes. But he nonetheless transforms everyone’s private information into common knowledge. Common knowledge is not the same thing as public information. Common knowledge is simply information, public or private, that everyone believes is shared by everyone else. It’s the crowd of tribesmen looking around and seeing that the entire crowd heard the Missionary that unlocks the private information in their heads and turns it into common knowledge. This is the power of the crowd watching the crowd, and for my money it’s the most potent behavioral force in human society.

Prior Epsilon Theory notes have focused on the role of the Missionary, and I’ll return to that aspect of the game in a moment. But today my primary focus is on the role of time in this game, and here’s the key: no one thinks he’s on the wrong side of common knowledge at the outset of the game. It takes time for individual tribesmen to observe other tribesmen and process the fact that the other tribesmen have not changed their behavior. I know this sounds really weird, that it’s the LACK of behavioral change in other tribesmen who you believe should be changing their behavior that eventually gets you to realize that they are wondering the same thing about you and your lack of behavioral change, which ultimately gets ALL of you blue-eyed tribesmen to change your behavior in a sudden flurry of activity. But that’s exactly the dynamic here. Even though there is zero behavioral change by any individual tribesman for p erhaps a long period of time, such that an external observer might think that the Missionary’s statement had no impact at all, the truth is that an enormous amount of mental calculations and changes are taking place within each and every tribesman’s head as soon as the common knowledge is created.

I’ve written at length about the portfolio construction corollary to phenotype, or the physical expression of a genetic code, and genotype, or the genetic code itself. The former gets all of the attention because it’s visible, even though the latter is where all the action really is, and that’s a problem. In modern society it means that we place an enormous emphasis on skin color as a signifier of otherness or differentiation, when really it deserves almost no attention at all. In portfolio management it means that we place an enormous emphasis on style boxes and asset classes as a signifier of diversification, when really there are far more telling manifestations. The dynamic of the Common Knowledge Game is another variation on this theme. For almost the entire duration of the game, the activity is internal and invisible, not external and visible, but it’s there all the same, bubbling beneath the behavioral surface until it final ly erupts. The more tribesmen with blue eyes, the longer the game simmers. And the longer the game simmers the more everyone – blue-eyed or not – questions whether or not he has blue eyes. It’s a horribly draining game to play from a mental or emotional perspective, even if nothing much is happening externally and regardless of which side of the common knowledge you are “truly” on.

If you haven’t observed exactly this sort of dynamic taking place in markets over the past five years, with nothing, nothing, nothing despite what seems like lots of relevant news, and then – boom! – a big move up or down as if out of nowhere – I just don’t know what to say. And I don’t know a single market participant, no matter how successful, who’s not bone-tired from all the mental anguish involved with trying to navigate these unfamiliar waters. These punctuated moves don’t come out of nowhere. They are part and parcel of the Common Knowledge Game, no more and no less, and understandable as such.

What starts the clock ticking on the “simmering stage” of the Common Knowledge Game? The Missionary’s public statement that everyone hears, creating the new common knowledge that everyone believes that everyone believes. How long does the simmering stage last? That depends on a couple of factors. First, as described above, the more game players who are on the wrong side of the new common knowledge, the longer the game simmers. Second, the dynamic depends critically on the fame or public acclaim of the Missionary, as well as the power of his or her microphone. A system with a few dominant Missionaries and only a few big microphones will create a clearer common knowledge more quickly, reducing the simmering time. Whether it’s Anna Wintour and Vogue or Janet Yellen and the Wall Street Journal, the scope and pace of game-playing depends directly on who is creating the common knowledge and how that message is amplified by mass med ia. Fashion changes much more quickly today than in, say, the 1930’s, because the “arbiters of taste” – what I’m calling Missionaries – are fewer, more famous, and have stronger media microphones at their disposal. Ditto with the investment world.

But has the clock started ticking on new common knowledge to change the dominant investment game? Has there been a perception-changing public statement from a powerful Missionary to make us question Central Bank Omnipotence, to make us question the color of our eyes? No, there hasn’t. There are clearly new CK games being played in subsidiary common knowledge structures – what I call Narratives – but not in this core Narrative of the Fed’s control over market outcomes. So for example, the market can go down, and more than a little, as the common knowledge around the subsidiary Narrative of The Fed Has Got Your Back comes undone with a second derivative shift from easing to tightening. The Fed itself is the Missionary on this new common knowledge. But the market can’t break so long as the common knowledge of Central Bank Omnipotence remains intact. So long as everyone knows that everyone knows that market outcomes ultimately depen d on Fed policy, then the Yellen put is firmly in place. If things get really bad, then the Fed can save us. We might argue about timing and reaction functions and the like, but everyone believes that everyone believes that the Fed has this ability. And because it’s such strong common knowledge, this ability will never be tested and the market will never break. A nice trick if you can pull it off, and until a Missionary with the clout of the Fed comes out and challenges this core common knowledge it’s a fait accompliwithin the structure of the game. Who has this sort of clout? Only two people – Mario Draghi and Angela Merkel. That’s who I watch and who I listen to for any signs of a crack in the Omnipotence Narrative, and so far … nothing. On the contrary, Draghi and Merkel have been totally on board with the program. We’re all going to be wearing hats for a long time so long as all the investment arbiters of taste stick with their story.< /p> There is, of course, a fly in this glorious ointment, and it’s the single most important difference between the dynamic of fashion markets and financial markets: political shocks and political dislocations can trump common knowledge and precipitate an economic and market dislocation. Wars and coups and revolutions certainly influence fashion, but obviously in a far less immediate and pervasive manner than they influence financial markets. The fashion world is an almost purely self-contained Common Knowledge Game, and the investment world is not. Where am I looking for a political shock that would be big enough to challenge the common knowledge that Central Banks are large and in charge, capable of bailing us out no matter what? It’s not the Ukraine. On the contrary, events there are public enough to give Draghi an excuse to move forward with negative deposit rates or however he intends to implement greater monetary policy accommodation, but peripheral enou gh to any real economic impact so that the ECB’s competence to manufacture an outcome is not questioned. It’s China. If you don’t think that the territorial tussles with Vietnam and Japan matter, if you don’t think that the mutual accusations and arrests of American and Chinese citizens matter, if you don’t think that the HUGE natural gas deal between Russia and China matters, if you don’t think that the sea change in Chinese monetary policy matters … well, you’re just not paying attention. A political shock here is absolutely large enough to challenge the dominant market game, and that’s what I’ll be exploring in the next few Epsilon Theory notes.

|

||

|

Copyright 2014 Mauldin Economics. All Rights Reserved. |

||

|

Outside the Box is a free weekly economic e-letter by best-selling author and renowned financial expert, John Mauldin. You can learn more and get your free subscription by visiting http://www.mauldineconomics.com. To subscribe to John Mauldin’s e-letter, please click here: Outside the Box and MauldinEconomics.com is not an offering for any investment. It represents only the opinions of John Mauldin and those that he interviews. Any views expressed are provided for information purposes only and should not be construed in any way as an offer, an endorsement, or inducement to invest and is not in any way a testimony of, or associated with, Mauldin’s other firms. John Mauldin is the Chairman of Mauldin Economics, LLC. He also is the President of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC (MWA) which is an investment advisory firm registered with multiple states, President and registered representative of Millennium Wave Securities, LLC, (MWS) member FINRAand SIPC, through which securities may be offered. MWS is also a Commodity Pool Operator (CPO) and a Commodity Trading Advisor (CTA) registered with the CFTC, as well as an Introducing Brok er (IB) and NFA Member. Millennium Wave Investments is a dba of MWA LLC and MWS LLC. This message may contain information that is confidential or privileged and is intended only for the individual or entity named above and does not constitute an offer for or advice about any alternative investment product. Such advice can only be made when accompanied by a prospectus or similar offering document. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Please make sure to review important disclosures at the end of each article. Mauldin companies may have a marketing relationship with products and services mentioned in this letter for a fee. Note: Joining the Mauldin Circle is not an offering for any investment. It represents only the opinions of John Mauldin and Millennium Wave Investments. It is intended solely for investors who have registered with Millennium Wave Investments and its partners at www.MauldinCircle.com or directly related websites. The Mauldin Circle may send out material that is provided on a confidential basis, and subscribers to the Mauldin Circle are not to send this letter to anyone other than their professional investment counselors. Investors should discuss any investment with their personal investment counsel. John Mauldin is the President of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC (MWA), which is an investment advisory firm registered with multiple states. John Mauldin is a registered representative of Millennium Wave Securities, LLC, (MWS), an FINRA registered broker-dealer. MWS is also a Commodity Pool Operator (CPO) and a Commodity Trading Advisor (CTA) registered with the CFTC, as wel l as an Introducing Broker (IB). Millennium Wave Investments is a dba of MWA LLC and MWS LLC. Millennium Wave Investments cooperates in the consulting on and marketing of private and non-private investment offerings with other independent firms such as Altegris Investments; Capital Management Group; Absolute Return Partners, LLP; Fynn Capital; Nicola Wealth Management; and Plexus Asset Management. Investment offerings recommended by Mauldin may pay a portion of their fees to these independent firms, who will share 1/3 of those fees with MWS and thus with Mauldin. Any views expressed herein are provided for information purposes only and should not be construed in any way as an offer, an endorsement, or inducement to invest with any CTA, fund, or program mentioned here or elsewhere. Before seeking any advisor’s services or making an investment in a fund, investors must read and examine thoroughly the respective disclosure document or offering memorandum. Since these firms and Mauld in receive fees from the funds they recommend/market, they only recommend/market products with which they have been able to negotiate fee arrangements. PAST RESULTS ARE NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. THERE IS RISK OF LOSS AS WELL AS THE OPPORTUNITY FOR GAIN WHEN INVESTING IN MANAGED FUNDS. WHEN CONSIDERING ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS, INCLUDING HEDGE FUNDS, YOU SHOULD CONSIDER VARIOUS RISKS INCLUDING THE FACT THAT SOME PRODUCTS: OFTEN ENGAGE IN LEVERAGING AND OTHER SPECULATIVE INVESTMENT PRACTICES THAT MAY INCREASE THE RISK OF INVESTMENT LOSS, CAN BE ILLIQUID, ARE NOT REQUIRED TO PROVIDE PERIODIC PRICING OR VALUATION INFORMATION TO INVESTORS, MAY INVOLVE COMPLEX TAX STRUCTURES AND DELAYS IN DISTRIBUTING IMPORTANT TAX INFORMATION, ARE NOT SUBJECT TO THE SAME REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS AS MUTUAL FUNDS, OFTEN CHARGE HIGH FEES, AND IN MANY CASES THE UNDERLYING INVESTMENTS ARE NOT TRANSPARENT AND ARE KNOWN ONLY TO THE INVESTMENT MANAGER. Alternative investment performance can be volatile. An investor could lose all or a substantial amount of his or her investment. Often, alternative investment fund and account managers have t otal trading authority over their funds or accounts; the use of a single advisor applying generally similar trading programs could mean lack of diversification and, consequently, higher risk. There is often no secondary market for an investor’s interest in alternative investments, and none is expected to develop. All material presented herein is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Opinions expressed in these reports may change without prior notice. John Mauldin and/or the staffs may or may not have investments in any funds cited above as well as economic interest. John Mauldin can be reached at 800-829-7273. |

After decades of working with defense technology companies, I know the ebb and flow of military spending all too well.

I remember that when the Cold War came to an end, the nation’s political leaders were talking enthusiastically about the so-called “peace dividend.”

That’s Washington-speak for Pentagon budget cuts that always seem to come after a major conflict has ended.

Many investors believe that with our presence in Iraq largely gone, defense firms will offer mediocre returns at best.

I’m not buying into it. I think massive profit opportunities are there. And the market and the government are lining up behind them…

Not Just a Bull, a National Imperative

Fact is, earlier this decade, several key defense contractors saw there were tough times ahead and revamped operations to do well with lean budgets.

More to the point, as current dramatic news makes all too clear, the U.S. needs a strong global military presence with an army, navy, air force, and Marine Corps second to none.

The escalating conflict in Ukraine is a great example of why the U.S. must maintain a strong defense structure. It includes the ability to support NATO allies against incursions into Europe.

But that’s not the only global threat we face…

Look at how aggressive China has become in its demand to control the South China Sea. Not only that, but North Korea’s unstable regime remains a looming threat.

So, while many investors are looking at other sectors because of the ongoing Washington budget battles, defense stocks as a group have greatly outperformed the overall market.

Here’s the thing. I grew up in a military household and have followed defense technology my entire career as an analyst.

In fact, I was in the tech trenches during the 1980s when President Reagan broke new ground with his tech-centric Strategic Defense Initiative, more commonly known as his “Star Wars” program.

So, I have seen first-hand the Pentagon and its prime contractors adapt to budget cuts and come back stronger every time. And they are brimming with advanced technology that gives America defense superiority.

Back U.S. Defense and Reap Huge Gains

What we want to do is take advantage of the all the opportunities to profit from tech breakthroughs and weapons programs that will permeate the entire sector.

That’s why I think investors would do well to take a good look at PowerShares Aerospace & Defense (NYSE: PPA). This is a cost-effective ETF made up of 80% defense and aerospace stocks from companies who are proven leaders.’

The fund has a solid mix of companies, including cutting-edge small caps like FLIR Systems Inc. (Nasdaq: FLIR), the world’s predominant maker of commercial thermal-imaging cameras.

There’s also the advanced materials firm Hexcel Corp. (NYSE: HXL), which supplies honeycomb composites to some of the biggest names in the aerospace industry.

But the heart of this ETF play is found in its top 10 holdings.

They include many well-capitalized companies that have succeeded for decades regardless of Washington’s defense budget battles.

Raytheon Company (NYSE: RTN) is a full-spectrum company that provides the Pentagon with systems for electronic warfare, laser rangefinders, military training, and advanced radar.

Plus, the company’s intercept vehicles, radars, and space sensors work together to protect the U.S. and its allies against ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, aircraft, and other threats.

Raytheon was recently awarded an $8.5 million contract by the Office of Naval Research to develop a digital radar system that is thought to be the world’s most advanced.

In this year’s first quarter, earnings per share increased 3% from the year ago quarter to $1.57. New bookings grew 19% to $4.3 billion. Trading at $97 a share, Raytheon has a $30 billion market cap.

For its part, Lockheed Martin Corp. (NYSE: LMT) is well-known for making military aircraft. But the firm also supplies combat ships and ground vehicles as well as advanced radar and tactical communications.

Indeed, this is a company that illustrates what I’ve been talking about in terms of realigning to take advantages of the sector’s broad changes. The company’s history dates back more than 100 years, but the modern firm came together in a 1995 merger.

Lockheed Martin’s reach also includes space exploration, satellite systems, and climate monitoring. Moreover, the company has deep expertise in biometrics, cyber security, and the booming field of cloud computing.

The company recently secured two contracts from the U.S. Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force, combining for $34 million to develop laser-guided bombs.

In this year’s first quarter, sales fell 4% to $10.7 billion, but profits rose 23% to $933 million. The company forecasts higher sales, operating margins, and cash flow for the full year. Trading at $162 a share, Lockheed Martin has a $51 billion market cap.

And Northrop Grumman Corp. (NYSE: NOC) has a wide spectrum of operations that cover everything from advanced sensors to missile defense to cyber security.

The company makes manned and unmanned aircraft for defense applications. But it’s also collaborating with Yamaha to develop an autonomous helicopter with onboard intelligence gathering equipment for such civilian uses as search and rescue and forest fire observations.

Northrop Grumman also provides the military with electronic warfare and infrared countermeasures. In addition, the firm gives us a strong play on sensor technologies, advanced materials, and laser weapons systems.

For the first quarter of 2014, sales fell 5% from the year-ago period to $5.8 billion, but earnings per share rose 23% to $2.63. Trading at $120 a share, Northrop Grumman has a $26 billion market cap.

Thus, for tech investors PPA offers us access to some of the best and most advanced systems on earth – everything from robotics to sensors and space exploration.

It sells for just a fraction of some of its big-cap members. PPA trades at just $32, less than one-third the price of even the cheapest of the three big-cap defense firms we talked about today.

And it offers us superior returns. Over the past two years, PPA has gained some 74%. That’s more than two-thirds better than the S&P 500’s return over the period of 44%.

Setting Up Perfectly for the Short Term (and Long)

This also is a great long-term play. See, no matter what happens in Washington over the next several years, America’s role as the world’s only real superpower means we have little choice but to fund a strong defense system.

Plus, the U.S. will continue to push the boundaries of tech-centric warfare. No matter which party is in power after 2016, advanced technology will continue to get strong fiscal support.

All of which means both the big-cap contractors and the small-cap cutting edge firms stand to gain, which will only provide more support and price appreciation for PPA.

Michael Robinson’s Strategic Tech Investor puts you directly in touch with high-tech research, analysis… stock picks and strategies from a sector that can double, triple – even quadruple your retirement savings faster than any other sector on earth. Just click here, and you’ll get Strategic Tech Investor and all of Michael Robinson’s technology reports for free.]

There can be little doubt that Thomas Piketty’s new book Capital in the 21st Century has struck a nerve globally. In fact, the Piketty phenomenon (the economic equivalent to Beatlemania) has in some ways become a bigger story than the ideas themselves. However, the book’s popularity is not at all surprising when you consider that its central premise: how radical wealth redistribution will create a better society, has always had its enthusiastic champions (many of whom instigated revolts and revolutions). What is surprising, however, is that the absurd ideas contained in the book could captivate so many supposedly intelligent people.

Prior to the 20th Century, the urge to redistribute was held in check only by the unassailable power of the ruling classes, and to a lesser extent by moral and practical reservations against theft. Karl Marx did an end-run around the moral objections by asserting that the rich became so only through theft, and that the elimination of private property held the key to economic growth. But the dismal results of the 20th Century’s communist revolutions took the wind out of the sails of the redistributionists. After such a drubbing, bold new ideas were needed to rescue the cause. Piketty’s 700 pages have apparently filled that void.

Any modern political pollster will tell you that the battle of ideas is won or lost in the first 15 seconds. Piketty’s primary achievement lies not in the heft of his book, or in his analysis of centuries of income data (which has shown signs of fraying), but in conjuring a seductively simple and emotionally satisfying idea: that the rich got that way because the return on invested capital (r) is generally two to three percentage points higher annually than economic growth (g). Therefore, people with money to invest (the wealthy) will always get richer, at a faster pace, than everyone else. Free markets, therefore, are a one-way road towards ever-greater inequality.

Since Pitketty sees wealth in terms of zero sum gains (someone gets rich by making another poor) he believes that the suffering of the masses will increase until this cycle is broken by either: 1) wealth destruction that occurs during war or depression (which makes the wealthy poorer) or 2) wealth re-distribution achieved through income, wealth, or property taxes. And although Piketty seems to admire the results achieved by war and depression, he does not advocate them as matters of policy. This leaves taxes, which he believes should be raised high enough to prevent both high incomes and the potential for inherited wealth.

Before proceeding to dismantle the core of his thesis, one must marvel at the absurdity of his premise. In the book, he states “For those who work for a living, the level of inequality in the United States is probably higher than in any other society at any time in the past, anywhere in the world.” Given that equality is his yardstick for economic success, this means that he believes that America is likely the worst place for a non-rich person to ever have been born. That’s a very big statement. And it is true in a very limited and superficial sense. For instance, according to Forbes, Bill Gates is $78 billion richer than the poorest American. Finding another instance of that much monetary disparity may be difficult. But wealth is measured far more effectively in other ways, living standards in particular.

For instance, the wealthiest Roman is widely believed to have been Crassus, a first century BC landowner. At a time when a loaf of bread sold for ½ of a sestertius, Crassus had an estimated net worth of 200 million sestertii, or about 400 million loaves of bread. Today, in the U.S., where a loaf of bread costs about $3, Bill Gates could buy about 25 billion of them. So when measured in terms of bread, Gates is richer. But that’s about the only category where that is true.

For instance, the wealthiest Roman is widely believed to have been Crassus, a first century BC landowner. At a time when a loaf of bread sold for ½ of a sestertius, Crassus had an estimated net worth of 200 million sestertii, or about 400 million loaves of bread. Today, in the U.S., where a loaf of bread costs about $3, Bill Gates could buy about 25 billion of them. So when measured in terms of bread, Gates is richer. But that’s about the only category where that is true.

Crassus lived in a palace that would have been beyond comprehension for most Romans. He had as much exotic food and fine wines as he could stuff into his body, he had hot baths every day, and had his own staff of servants, bearers, cooks, performers, masseurs, entertainers, and musicians. His children had private tutors. If it got too hot, he was carried in a private coach to his beach homes and had his servants fan him 24 hours a day. In contrast, the poorest Romans, if they were not chained to an oar or fighting wild beasts in the arena, were likely toiling in the fields eating nothing but bread, if they were lucky. Unlike Crassus, they had no access to a varied diet, health care, education, entertainment, or indoor plumbing.

In contrast, look at how Bill Gates lives in comparison to the poorest Americans. The commodes used by both are remarkably similar, and both enjoy hot and cold running water. Gates certainly has access to better food and better health care, but Americans do not die of hunger or drop dead in the streets from disease, and they certainly have more to eat than just bread. For entertainment, Bill Gates likely turns on the TV and sees the same shows that even the poorest Americans watch, and when it gets hot he turns on the air conditioning, something that many poor Americans can also do. Certainly flipping burgers in a McDonald’s is no walk in the park, but it is far better than being a galley slave. The same disparity can be made throughout history, from Kublai Khan, to Louis XIV. Monarchs and nobility achieved unimagined wealth while surrounded by abject poverty. The same thing happens today in places like North Korea, where Kim Jong-un lives in splendor while his citizens literally starve to death.

Unemployment, infirmity or disabilities are not death sentences in America as they were in many other places throughout history. In fact, it’s very possible here to earn more by not working. Yet Piketty would have us believe that the inequality in the U.S. now is worse than in any other place, at any other time. If you can swallow that, I guess you are open to anything else he has to serve.

All economists, regardless of their political orientation, acknowledge that improving productive capital is essential for economic growth. We are only as good as the tools we have. Food, clothing and shelter are so much more plentiful now than they were 200 years ago because modern capital equipment makes the processes of farming, manufacturing, and building so much more efficient and productive (despite government regulations and taxes that undermine those efficiencies). Piketty tries to show that he has moved past Marx by acknowledging the failures of state-planned economies.

But he believes that the state should place upper limits on the amount of wealth the capitalists are allowed to retain from the fruits of their efforts. To do this, he imagines income tax rates that would approach 80% on incomes over $500,000 or so, combined with an annual 10% tax on existing wealth (in all its forms: land, housing, art, intellectual property, etc.). To be effective, he argues that these confiscatory taxes should be imposed globally so that wealthy people could not shift assets around the world to avoid taxes. He admits that these transferences may not actually increase tax revenues, which could be used, supposedly, to help the lives of the poor. Instead he claims the point is simply to prevent rich people from staying that way or getting that way in the first place.

Since it would be naive to assume that the wealthy would continue to work and invest at their usual pace once they crossed over Piketty’s income and wealth thresholds, he clearly believes that the economy would not suffer from their disengagement. Given the effort it takes to earn money and the value everyone places on their limited leisure time, it is likely that many entrepreneurs will simply decide that 100% effort for a 20% return is no longer worth it. Does Piketty really believe that the economy would be helped if the Steve Jobses and Bill Gateses of the world simply decided to stop working once they earned a half a million dollars?

Because he sees inherited wealth as the original economic sin, he also advocates tax policies that will put an end to it. What will this accomplish? By barring the possibility of passing on money or property to children, successful people will be much more inclined to spend on luxury services (travel and entertainment) than to save or plan for the future. While most modern economists believe that savings detract from an economy by reducing current spending, it is actually the seed capital that funds future economic growth. In addition, businesses managed for the long haul tend to offer incremental value to society. Bringing children into the family business also creates value, not just for shareholders but for customers. But Piketty would prefer that business owners pull the plug on their own companies long before they reach their potential value and before they can bring their children into the business. How exactly does this benefit society?

If income and wealth are capped, people with capital and incomes above the threshold will have no incentive to invest or make loans. After all, why take the risks when almost all the rewards would go to taxes? This means that there will be less capital available to lend to businesses and individuals. This will cause interest rates to rise, thereby dampening economic growth. Wealth taxes would exert similar upward pressure on interest rates by cutting down on the pool of capital that is available to be lent. Wealthy people will know that any unspent wealth will be taxed at 10% annually, so only investments that are likely to earn more than 10%, by a margin wide enough to compensate for the risk, would be considered. That’s a high threshold.

The primary flaw in his arguments are not moral, or even computational, but logical. He notes that the return of capital is greater than economic growth, but he fails to consider how capital itself “returns” benefits for all. For instance, it’s easy to see that Steve Jobs made billions by developing and selling Apple products. All you need to do is look at his bank account. But it’s much harder, if not impossible, to measure the much greater benefit that everyone else received from his ideas. It only comes out if you ask the right questions. For instance, how much would someone need to pay you to voluntarily give up the Internet for a year? It’s likely that most Americans would pick a number north of $10,000. This for a service that most people pay less than $80 per month (sometimes it’s free with a cup of coffee). This differential is the “dark matter” that Piketty fails to see, because he doesn’t even bother to look.

Somehow in his decades of research, Piketty overlooks the fact that the industrial revolution reduced the consequences of inequality. Peasants, who had been locked into subsistence farming for centuries, found themselves with stunningly improved economic prospects in just a few generations. So, whereas feudal society was divided into a few people who were stunningly rich and the masses who were miserably poor, capitalism created the middle class for the first time in history and allowed for the possibility of real economic mobility. As a by-product, some of the more successful entrepreneurs generated the largest fortunes ever measured. But for Piketty it’s only the extremes that matter. That’s because he, and his adherents, are more driven by envy than by a desire for success. But in the real world, where envy is inedible, living standards are the only things that matter.

Peter Schiff is the CEO and Chief Global Strategist of Euro Pacific Capital, best-selling author and host of syndicated Peter Schiff Show.

Catch Peter’s latest thoughts on the U.S. and International markets in the Euro Pacific Capital Spring 2014 Global Investor Newsletter!

As VIX, the CBOE

As VIX, the CBOE