Investment/Finances

Ben S. Bernanke doesn’t know how lucky he is. Tongue-lashings from Bernie Sanders, the populist senator from Vermont, are one thing. The hangman’s noose is another. Section 19 of this country’s founding monetary legislation, the Coinage Act of 1792, prescribed the death penalty for any official who fraudulently debased the people’s money. Was the massive printing of dollar bills to lift Wall Street (and the rest of us, too) off the rocks last year a kind of fraud? If the U.S. Senate so determines, it may send Mr. Bernanke back home to Princeton. But not even Ron Paul, the Texas Republican sponsor of a bill to subject the Fed to periodic congressional audits, is calling for the Federal Reserve chairman’s head.

I wonder, though, just how far we have really come in the past 200-odd years. To give modernity its due, the dollar has cut a swath in the world. There’s no greater success story in the long history of money than the common greenback. Of no intrinsic value, collateralized by nothing, it passes from hand to trusting hand the world over. More than half of the $923 billion’s worth of currency in circulation is in the possession of foreigners.

In ancient times, the solidus circulated far and wide. But it was a tangible thing, a gold coin struck by the Byzantine Empire. Between Waterloo and the Great Depression, the pound sterling ruled the roost. But it was convertible into gold—slip your bank notes through a teller’s window and the Bank of England would return the appropriate number of gold sovereigns. The dollar is faith-based. There’s nothing behind it but Congress.

But now the world is losing faith, as well it might. It’s not that the dollar is overvalued—economists at Deutsche Bank estimate it’s 20% too cheap against the euro. The problem lies with its management. The greenback is a glorious old brand that’s looking more and more like General Motors.

You get the strong impression that Mr. Bernanke fails to appreciate the tenuousness of the situation—fails to understand that the pure paper dollar is a contrivance only 38 years old, brand new, really, and that the experiment may yet come to naught. Indeed, history and mathematics agree that it will certainly come to naught. Paper currencies are wasting assets. In time, they lose all their value. Persistent inflation at even seemingly trifling amounts adds up over the course of half a century. Before you know it, that bill in your wallet won’t buy a pack of gum.

For most of this country’s history, the dollar was exchangeable into gold or silver. “Sound” money was the kind that rang when you dropped it on a counter. For a long time, the rate of exchange was an ounce of gold for $20.67. Following the Roosevelt devaluation of 1933, the rate of exchange became an ounce of gold for $35. After 1933, only foreign governments and central banks were privileged to swap unwanted paper for gold, and most of these official institutions refrained from asking (after 1946, it seemed inadvisable to antagonize the very superpower that was standing between them and the Soviet Union). By the late 1960s, however, some of these overseas dollar holders, notably France, began to clamor for gold. They were well-advised to do so, dollars being in demonstrable surplus. President Richard Nixon solved that problem in August 1971 by suspending convertibility altogether. From that day to this, in the words of John Exter, Citibanker and monetary critic, a Federal Reserve “note” has been an “IOU nothing.”

To understand the scrape we are in, it may help, a little, to understand the system we left behind. A proper gold standard was a well-oiled machine. The metal actually moved and, so moving, checked what are politely known today as “imbalances.” Say a certain baseball-loving North American country were running a persistent trade deficit. Under the monetary system we don’t have and which only a few are yet even talking about instituting, the deficit country would remit to its creditors not pieces of easily duplicable paper but scarce gold bars. Gold was money—is, in fact, still money—and the loss would set in train a series of painful but necessary adjustments in the country that had been watching baseball instead of making things to sell. Interest rates would rise in that deficit country. Its prices would fall, its credit would be curtailed, its exports would increase and its imports decrease. At length, the deficit country would be restored to something like competitive trim. The gold would come sailing back to where it started. As it is today, dollars are piled higher and higher in the vaults of America’s Asian creditors. There’s no adjustment mechanism, only recriminations and the first suggestion that, from the creditors’ point of view, enough is enough.

So in 1971, the last remnants of the gold standard were erased. And a good thing, too, some economists maintain. The high starched collar of a gold standard prolonged the Great Depression, they charge; it would likely have deepened our Great Recession, too. Virtue’s the thing for prosperity, they say; in times of trouble, give us the Ben S. Bernanke school of money conjuring. There are many troubles with this notion. For one thing, there is no single gold standard. The version in place in the 1920s, known as the gold-exchange standard, was almost as deeply flawed as the post-1971 paper-dollar system. As for the Great Recession, the Bernanke method itself was a leading cause of our troubles. Constrained by the discipline of a convertible currency, the U.S. would have had to undergo the salutary, unpleasant process described above to cure its trade deficit. But that process of correction would—I am going to speculate—have saved us from the near-death financial experience of 2008. Under a properly functioning gold standard, the U.S. would not have been able to borrow itself to the threshold of the poorhouse.

Anyway, starting in the early 1970s, American monetary policy came to resemble a game of tennis without the net. Relieved of the irksome inhibition of gold convertibility, the Fed could stop worrying about the French. To be sure, it still had Congress to answer to, and the financial markets, as well. But no more could foreigners come calling for the collateral behind the dollar, because there was none. The nets came down on Wall Street, too. As the idea took hold that the Fed could meet any serious crisis by carpeting the nation with dollar bills, bankers and brokers took more risks. New forms of business organization encouraged more borrowing. New inflationary vistas opened.

….read more HERE. (start just below the images of the coins on the left)

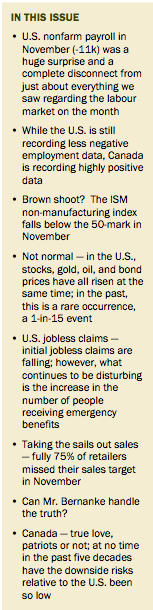

IN THIS ISSUE

U.S. nonfarm payroll in November (-11k) was a huge surprise and a complete disconnect from just about everything we saw regarding the labour market on the month

While the U.S. is still recording less negative employment data, Canada is recording highly positive data…. …..read all HERE.

…..read all HERE.

“U.S. President Barack Obama announced the broad structure of his Afghanistan strategy in a speech at West Point on Tuesday evening”.

The strategy had three core elements. First, he intends to maintain pressure on al Qaeda on the Afghan-Pakistani border and in other regions of the world. Second, he intends to blunt the Taliban offensive by sending an additional 30,000 American troops to Afghanistan, along with an unspecified number of NATO troops he hopes will join them. Third, he will use the space created by the counteroffensive against the Taliban and the resulting security in some regions of Afghanistan to train and build Afghan military forces and civilian structures to assume responsibility after the United States withdraws. Obama added that the U.S. withdrawal will begin in July 2011, but provided neither information on the magnitude of the withdrawal nor the date when the withdrawal would conclude. He made it clear that these will depend on the situation on the ground, adding that the U.S. commitment is finite.

Related Special Topic Page

In understanding this strategy, we must begin with an obvious but unstated point: The extra forces that will be deployed to Afghanistan are not expected to defeat the Taliban. Instead, their mission is to reverse the momentum of previous years and to create the circumstances under which an Afghan force can take over the mission. The U.S. presence is therefore a stopgap measure, not the ultimate solution.

The ultimate solution is training an Afghan force to engage the Taliban over the long haul, undermining support for the Taliban, and dealing with al Qaeda forces along the Pakistani border and in the rest of Afghanistan. If the United States withdraws all of its forces as Obama intends, the Afghan military would have to assume all of these missions. Therefore, we must consider the condition of the Afghan military to evaluate the strategy’s viability.

Afghanistan vs. Vietnam

Obama went to great pains to distinguish Afghanistan from Vietnam, and there are indeed many differences. The core strategy adopted by Richard Nixon (not Lyndon Johnson) in Vietnam, called “Vietnamization,” saw U.S. forces working to blunt and disrupt the main North Vietnamese forces while the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) would be trained, motivated and deployed to replace U.S. forces to be systematically withdrawn from Vietnam. The equivalent of the Afghan surge was the U.S. attack on North Vietnamese Army (NVA) bases in Cambodia and offensives in northern South Vietnam designed to disrupt NVA command and control and logistics and forestall a major offensive by the NVA. Troops were in fact removed in parallel with the Cambodian offensives.

Nixon faced two points Obama now faces. First, the United States could not provide security for South Vietnam indefinitely. Second, the South Vietnamese would have to provide security for themselves. The role of the United States was to create the conditions under which the ARVN would become an effective fighting force; the impending U.S. withdrawal was intended to increase the pressure on the Vietnamese government to reform and on the ARVN to fight.

Many have argued that the core weakness of the strategy was that the ARVN was not motivated to fight. This was certainly true in some cases, but the idea that the South Vietnamese were generally sympathetic to the Communists is untrue. Some were, but many weren’t, as shown by the minimal refugee movement into NVA-held territory or into North Vietnam itself contrasted with the substantial refugee movement into U.S./ARVN-held territory and away from NVA forces. The patterns of refugee movement are, we think, highly indicative of true sentiment.

Certainly, there were mixed sentiments, but the failure of the ARVN was not primarily due to hostility or even lack of motivation. Instead, it was due to a problem that must be addressed and overcome if the Afghanistation war is to succeed. That problem is understanding the role that Communist sympathizers and agents played in the formation of the ARVN.

By the time the ARVN expanded — and for that matter from its very foundation — the North Vietnamese intelligence services had created a systematic program for inserting operatives and recruiting sympathizers at every level of the ARVN, from senior staff and command positions down to the squad level. The exploitation of these assets was not random nor merely intended to undermine moral. Instead, it provided the NVA with strategic, operational and tactical intelligence on ARVN operations, and when ARVN and U.S. forces operated together, on U.S. efforts as well.

In any insurgency, the key for insurgent victory is avoiding battles on the enemy’s terms and initiating combat only on the insurgents’ terms. The NVA was a light infantry force. The ARVN — and the U.S. Army on which it was modeled — was a much heavier, combined-arms force. In any encounter between the NVA and its enemies the NVA would lose unless the encounter was at the time and place of the NVA’s choosing. ARVN and U.S. forces had a tremendous advantage in firepower and sheer weight. But they had a significant weakness: The weight they bought to bear meant they were less agile. The NVA had a tremendous weakness. Caught by surprise, it would be defeated. And it had a great advantage: Its intelligence network inside the ARVN generally kept it from being surprised. It also revealed weakness in its enemies’ deployment, allowing it to initiate successful offensives.

All war is about intelligence, but nowhere is this truer than in counterinsurgency and guerrilla war, where invisibility to the enemy and maintaining the initiative in all engagements is key. Only clear intelligence on the enemy’s capability gives this initiative to an insurgent, and only denying intelligence to the enemy — or knowing what the enemy knows and intends — preserves the insurgent force.

The construction of an Afghan military is an obvious opportunity for Taliban operatives and sympathizers to be inserted into the force. As in Vietnam, such operatives and sympathizers are not readily distinguishable from loyal soldiers; ideology is not something easy to discern. With these operatives in place, the Taliban will know of and avoid Afghan army forces and will identify Afghan army weaknesses. Knowing that the Americans are withdrawing as the NVA did in Vietnam means the rational strategy of the Taliban is to reduce operational tempo, allow the withdrawal to proceed, and then take advantage of superior intelligence and the ability to disrupt the Afghan forces internally to launch the Taliban offensives.

The Western solution is not to prevent Taliban sympathizers from penetrating the Afghan army. Rather, the solution is penetrating the Taliban. In Vietnam, the United States used signals intelligence extensively. The NVA came to understand this and minimized radio communications, accepting inefficient central command and control in return for operational security. The solution to this problem lay in placing South Vietnamese into the NVA. There were many cases in which this worked, but on balance, the NVA had a huge advantage in the length of time it had spent penetrating the ARVN versus U.S. and ARVN counteractions. The intelligence war on the whole went to the North Vietnamese. The United States won almost all engagements, but the NVA made certain that it avoided most engagements until it was ready.

In the case of Afghanistan, the United States has far more sophisticated intelligence-gathering tools than it did in Vietnam. Nevertheless, the basic principle remains: An intelligence tool can be understood, taken into account and evaded. By contrast, deep penetration on multiple levels by human intelligence cannot be avoided.

Pakistan’s Role

….read more HERE.

It seems yet another multibillion dollar bubble-enterprise has popped. The tiny but rich little city state of Dubai has blown its wad. This week they announced that they cannot make their loan payments. They need to postpone them for another six months.

Dubai’s early claim to fame was she pumps a lot of oil: around 240,000 barrels a day. Then they decided to diversify into tourism. They hired a group of high powered western MBAs, put together a great business plan and gave birth to a spectacular modern city, an architect’s dream come true.

But there’s a catch. They borrowed the money to build their Oz-city. Let’s calculate Dubai’s gross income if oil sells at $100 per barrel; then we’ll re-calculate at $50 a barrel. I apologize for this painstakingly obvious exercise, but I’m sure you see the point. Dubai’s most important source of income is totally dependent on the price of crude oil, which can rise and fall dramatically. So, when the government of Dubai borrowed the $59 billion to finance their dream city, the lenders would have known that their ability to repay those billions would depend on the price of crude.

But, it’s not that simple. Oil is a depleting asset. One day Dubai will run out. [Current estimates give them about 20 years.] Dubai’s ability to repay its debt is tied to fluctuations in crude oil prices and then they will run out. So, when calculating how much money they should lend this ambitious little city, the banks know all this. What bank on earth would ever lend Dubai so much money that she would be unable to pay the money back?

Maybe the bankers were in dream land too. Maybe they had seen the 1989 movie Field of Dreams and believed the slogan: “build it and he will come.” In Field of Dreams, some entrepreneur built a baseball diamond in the middle of a corn field. And, sure enough, by the end of the movie, there were people playing baseball on it. It’s the Las Vegas story: they built a city in the middle of the Nevada desert, and sure enough, people came. Maybe that’s what Dubai’s lenders were thinking. But last week’s neo-bankruptcy puts that dream in doubt.

We can’t blame the ambitious leaders of Dubai for going for broke. They took a mega-risk, in hopes that their little desert nation could emerge into a modern economy. And it looks like they will lose. It’s the bankers that worry me.

All an honest banker could ever have expected to make on the Dubai Dream Field loans was interest on their money. Why would they make such long shot loans? Our guess is there was something more in this deal than boring bank real estate financing. There was something sexy, some sizzle, something not cut from a conservative banker’s cloth. The Dubai deal smacks of some secret, yet unspoken. In the mean time, the Dubai default shock ripples around the world’s banking system and the world’s financial markets. It’s not a huge default. American billionaires Bill Gates and Warren Buffet were once worth more than this whole Dubai default. No doubt the world’s banking system will weather this little desert storm.

Now it seems it would have been better for the citizens of Dubai if their leaders had had more conservative business plans. And it would have been better for all of us if world bankers had been less aggressive.

What about you?

Are you a high roller? Are you betting on a long shot high roller’s dream? After seeing what happened to the stock market in 2008, are you still over-exposed? In 2001-2 the stock markets dropped about 45%. In 2008 it happened again. The stock market has become a high roller’s game. In 2008 corporate America came undone. In 2008-09 world banking came undone. And the Dubai default is showing us that we still live in risky times because of yesterday’s high roller bankers. Is it time to become conservative again? Is it time to quietly re-think your personal financial plan and make adjustments for the high risk times we live in? It seems we can’t trust big banks or big corporations to provide a financially stable world. We have to provide our own financial stability. It’s time to become more conservative in our personal finances.

Ed Note: Highly recommend you read:

THE CASTLEMOORE INVESTMENT COMMENTARY

….it has great commentary and charts in it examples below. Even some 10 Rodney Dangerfield humor “My wife had her drivers test the other day. She got 8 out of 10. The other 2 guys jumped clear.”

….and serious

Bob Farrell’s 10 Rules of Trading

Mr. Farrell, Merrill Lynch’s chief market strategist from 1967-1992 penned

some pretty decent “Rules to Remember”…

1) Markets tend to return to the mean over time.

2) Excesses in one direction will lead to an opposite excess in the

other direction.

3) There are no new eras – excesses are never permanent.

4) Exponential rapidly rising or falling markets usually go further

than you think, but they do not correct by going sideways.

5) The public buys the most at the top and the least at the bottom.

6) Fear and greed are stronger than long-term resolve.

7) Markets are strongest when they are broad and weakest when

they narrow to a handful of blue chip names.

8) Bear markets have three stages – sharp down – reflexive rebound –

a drawn-out fundamental downtrend.

9) When all the experts and forecasts agree – something else is going

to happen.

10) Bull markets are more fun than bear markets

Rodney Dangerfield quotes:

Ever see one of those “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” statues or pictures? The ones with the three monkeys, one covering his eyes, one covering his ears, and one covering his mouth?

That’s pretty much what the Federal Reserve appears to be doing now when it comes to the asset markets …

Stocks up 67 percent from their lows? No worries.

Junk bonds up 52 percent this year — the biggest increase in the history of the high-yield debt market, even as default rates are hitting their highest levels since the Great Depression? That’s cool, too.

Gold at all-time highs of over $1,170 an ounce? Fine with us.

Crude at $80 and climbing? Agriculture commodities ramping? Surging prices for sugar … cotton … wheat … platinum … silver … copper … aluminum … lead … ZINC? Pu-shaw! Nothing to worry about.

Is it just me or are we apparently ready for round THREE of idiotic asset speculation fueled by too much easy money? Sure looks like it …

Deny, Deny, Deny

You think I’m exaggerating the Fed’s blissful state of ignorance here? Don’t take my word for it. Take THEIRS!

In just the past several days, Fed speakers have practically been tripping all over themselves to deny the existence of any asset bubbles.

First up was Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke in New York. He said:

“It is inherently extraordinarily difficult to know whether an asset’s price is in line with its fundamental value,” … but “It’s not obvious to me in any case that there’s any large misalignments currently in the U.S. financial system.”

Next in line was Fed Vice-Chairman Donald Kohn in Illinois. He said:

“The prices of assets in U.S. financial markets do not appear to be clearly out of line with the outlook for the economy and business prospects as well as the level of risk-free interest rates.”

Then there was San Francisco Fed President Janet Yellen. She basically waved off the idea of raising rates to combat surging asset prices, saying in Hong Kong that:

“Further research into the connections among monetary policy, the banking and financial sectors, and systemic risk is needed to help answer this question.”

That’s bureaucrat-speak for “We’re going to kick the can down the road.”

But St. Louis Fed President James Bullard trumped them all. In a speech in his hometown, he essentially pledged that the Fed would keep rates unchanged through 2012. His comments:

“If you look at the last two recessions, in each case the FOMC waited two and a half to three years before we started our tightening campaign … If we took that as a benchmark, that would put us in the first half of 2012.”

Yes Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. And he lives in Washington, DC! He’s going to give you more than two years of abundant liquidity and cheap money. Go ahead and party and speculate like mad because the cops aren’t going to shut things down anytime soon.

What Does this Mean For

Investors Like You?

Well, in my trading services, I have been aggressively long various ETFs and options despite technical indicators that don’t look incredibly bullish. My subscribers are sitting on a couple rounds of triple-digit gains, and in my view, more are coming down the pike.

Why the success?

Because I’m keeping it simple. This is an environment where any and all assets are levitating on a sea of easy Fed money. We had the tech stock bubble. We had the housing bubble. Now we have an “everything” bubble — courtesy of the “See nothing, hear nothing, speak nothing” crowd at the Fed.

I say ride it while it lasts. Make as much money as you can. But keep an eye on the exit door, take profits along the way, and use trading tools like trailing stop losses.

Because I will guarantee you right here and now that this Fed-fueled insanity will end in yet another epic blow up. And investors who overstay their welcome are going to get creamed … again.

Until next time,

Mike

This investment news is brought to you by Money and Markets. Money and Markets is a free daily investment newsletter from Martin D. Weiss and Weiss Research analysts offering the latest investing news and financial insights for the stock market, including tips and advice on investing in gold, energy and oil. Dr. Weiss is a leader in the fields of investing, interest rates, financial safety and economic forecasting. To view archives or subscribe, visit http://www.moneyandmarkets.com.