Daily Updates

I have always loved Canada. From the time I read the biographies of Bobby Orr and Bobby Hull, as a kid, to the times I travelled to Toronto, Montreal, Quebec City, Prince Edward Island, and the Gaspe Peninsula as a teenager, to more recent visits to Vancouver for the World Outlook Conference …

…. not to mention my love of the national sport, Hockey, or my time living with a bunch of “crazy Canucks” at Delta Kappa Epsilon, the “hockey frat” at Colgate University, I have always had a place in my heart for Canada, and for Canadians. From the Maple Leaf flag, to the Montreal Canadian’s home hockey jersey, I still feel warm when I hear the Canadian National Anthem …

…”Oh Canada, glorious and free, we stand on guard, we stand on guard for thee”.

Indeed,

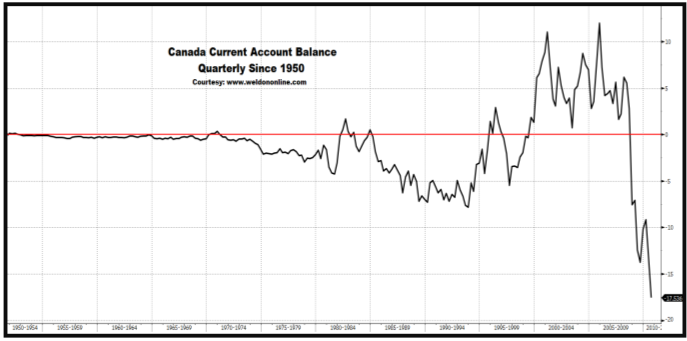

Indeed, as noted in the chart below, Canada‟s Current Account Balance plunged to its DEEPEST DEFICIT EVER during the 3Q.

**Ed Note: this article goes on for 14 pages with some extraordinary charts to give the visual picture. One of the closing comments is “… Gold stands on guard, as the best “protector” of wealth in Canada”. See how to read more at the bottom below.

More from Greg: Finally, in keeping with today’s Canadian theme, we would like to formally “introduce” the latest addition to Weldon Financial, Katelyn Ellis, math-physics whiz, and graduate of Canada’s McGill University. Ms. Ellis will serve as my new “trading assistant”, hired to help handle the inflow of “demand” linked to our Managed Futures business, and the re-opening of our Macro- Discretionary, Diversified Global “trading” Program, along with the introduction of our new Long-Short Commodity Only “portfolio” Program.

Welcome Katelyn, who just passed her Series 3 Exam with flying colors …… as in the red and white of the Canadian Maple Leaf Flag.

To read more of this penetrating 14 page article & Charts Titled MACRO-CANADA: We Stand On Guard For Thee …

…..Weldon’s Money Monitor offers a FREE 30 Day Trial Subscription. For subscription information contact Eileen @Weldononline.com or Visit www.Weldononline.com for a FREE Trial.

A FREE 30 Day Trial Subscription is defined as a single Trial that is limited to a one-time Signup. Signing up for multiple trials under different names, Fraudulent contact information is illegal. Weldon’s Money Monitor takes this seriously..

“If you bought a treasury bond five years ago, versus buying gold at $450, you got your money back at a nominal, miniscule yield because it’s ‘safe’ guaranteed investment. The problem is the million dollars you got back it buys one third the amount of gold it could have bought 5 years ago. That in a nutshell is the debasement of the currency at work. It is the lower standard of living at work.”

Ed Note: Michael Campbell calls Greg Weldon – “The One Analyst other Analysts can’t Wait to Read.”

Ed Note: Condensed version of this article HERE

“Gold still has significant upside” – and why…..

Michael Campbell: I’m glad you’re with us. I call Greg Weldon’s research the top research in North America. He is the guy who does all the work that other analysts and institutions want to have a look at.

In the last two weeks we’ve had the Irish bail out and the United States promised to help buoy up the International Monetary Fund, with another trillion dollars. Are we trying to solve a huge debt problem by taking on more debt? What are the implications of this?

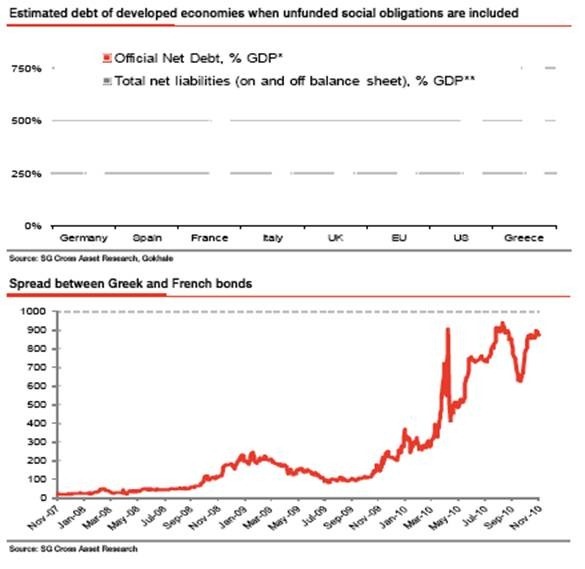

Greg: Well, I think actually the last time I was on your show Michael we discussed that Greece at the time seemed to be an isolated event and how ludicrous that whole process was. This only intensifies when you think that 25 out of 27 EU nations are in violation of rules on either debts or deficit relative to their GDP. We’ve been saying for a long time that for Europe to to bail out Europe is ridiculous. To think that the US is going to commit a trillion dollars to any bail outs is even more ludicrous. Really the spark in the stock markets around the world was that comment from an unnamed US official.

The European Central Bank has been in a program to buy debt, but they sterilized that money that was in the system, they withdraw at the back end. So they are not even really playing ball to begin with to the degree that the Fed has in the US. To pin your hopes on all of this is highly suspect. But having said that, the European Central Bank is expanding their balance sheet again. The Bank of Japan balance sheet just hit a new interim high. The US bought a lot of bonds and unfortunately they’ve had mortgage roll ups so they haven’t yet in net expanded their balance sheet to new heights, but they’re in the process of doing that. So when you have the three major central banks in the world expanding their balance sheets, that does provide some underpinning in terms of liquidity. To think that that’s a solution to this long term problems is absolutely ludicrous.

Michael: In your view then Greg, it’s not a matter of if we have a day of reckoning, it’s just when?

Greg: There is no way out. This is the cycle that you’re caught in and you can never underestimate the ability of monetary officials around the world to get creative. This is a bubble that goes back to the US removing the dollar from the gold standard. What we’ve entered into is an absolute the day of reckoning. But it’s not here yet because we’re going to keep going through these vacillations where they pump it up and dump until they can’t do it anymore. The second you pull the rag out from under the market in terms of support either fiscally or monetarily, it’s a nightmare waiting to happen.

So they have boxed themselves into a corner where pump it up is the only way out, but inevitably is doomed to fail. And timing that failure is what is just so difficult and becomes increasingly difficult as these vacillations become more and more extreme. You might liken it to an EKG where you have a nice little pattern of up and down, up and down, up and down and in ’97, ’98 crisis that pattern became a little more wild, in 2000, 2001 more wild, lastly in 2007, you’re into the heart attack stage.

Michael: How does that manifest? Is it deflation or hyper-inflation?

Greg: It’s both Michael. This is a whole theme to talk about. On the one hand the bail out of Ireland calls for them to accelerate the €15 billion budget adjustments over the next five years. In fact they want it to be more extreme, in other words less spending, higher taxes and at $15 billion adjustment that the parties in power there just put forth. This has created a completely fractured political debate where the Green Party has pulled their support of the government and now they might have to call elections. It could become a referendum to the people who of course are not going to vote for even more extreme austerity.

So it becomes a situation where people are getting hurt, it becomes less easy to wiggle out of it by throwing more paper at it, and you can even liken this to the situation in the US now too where there is this push for austerity. The political will and the will of the people to endure pain to make that happen becomes the balancing act and the fine line. You’re looking at a situation in the US where the second they cut federal support, you have states the municipalities that are in deep, deep trouble; in fact declaring bankruptcy so I think that this issue applies in Europe.We said years ago when we first started talking you, that the housing market and the results in the US banking situation which just happened that it would expand and you wouldn’t see any kind of real potential end of days until you had a European state default and a US state default. This is kind of the trend of where things are going right now.

Michael: There’s huge pension problems that exist in the world today and they are already under funded in the extreme. When does the media really recognize how severe the problem is?t

Greg: Ireland and the US and New Jersey are the most fiscally problematic places. I’m of Irish heritage, grew up in New Jersey, so it is painful to watch from a personal perspective but it impacts everybody. There are things going on in Asia and in other places in the world which are growth orientated but also problematic from the perspective of sustainability. Even when you mention Canada, by some metrics Vancouver is among the most overpriced real estate in the world. The reality and the math is that Canadians are totally tied into this. So Europe is really bailing out Europe; it’s not about bailing out Ireland, it’s more about making sure that the entire European banking system doesn’t come unglued.

Michael: There needs to be some sorts of restraint on government’s spending but in my experience the only way you can get the popluous to agree is if its someone else who has to cut back. Therefore is politics completely unable to handle it unless you get a a crisis situation?

Greg: Someone’s got to feel the pain and no one wants to feel the pain. It’s much easier to print more money to cover up that pain and ultimately that’s what happens.That’s he human condition, and the business the Fed and other central banks are in now is to do whatever they have to do to circumvent the pain of debt deflation. They feel they can fight an inflation, a hyper-reflation so they want to push for that. And they’ll probably keep pushing until they get it, or if they can’t get it, that’s your nightmare scenario.

Michael: You wrote the Gold Trading Boot Camp in 2006 in which you chronicled the kind of situation financially that we’re finding ourselves in right now and about taking advantage of gold as a protection against these kind of events. Where do you think gold is right now?

Greg: Gold still has significant upside. We actually became a little bit more cautious on precious metals about six weeks ago, when it looked like global interest rates had started to rise. But as we mentioned before the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet is expanding again, the ECB expanding its balance sheet and the Fed doing the same. As soon as these mortgage roll offs get out of the way the feds balance sheet should explode. So this certainly is positive for Gold.

More importantly in the bigger picture, when you take a look at gold prices in every currency in the world, it’s not a dollar move. Gold is gaining against every single currency in the world. The flip side of that is that every currency in the world depreciating relative to gold because central banks are debasing money everywhere. That’s the bottom line when talking about gold. That’s what people tend to miss, tend to overlook, that is what is really at the core of this. It’s kind of veiled, it’s kind of hidden, and no matter which way it goes, whether it is a successful hyper-reflation or whether it is a downturn to debt deflation, either scenario incorporates a lower standard of living.

This is what you’re saying when you’re talking about what’s happening in cities in the US and in Ireland where state employees are undergoing wage freezes. The bottom line is more unemployment, more chronically unemployed who can’t find jobs. This is the embedded reality of economics and it means a lower standard of living. For example the debasement of the currency means if you bought a treasury bond five years ago, versus buying gold at $450, you got your money back because it’s ‘safe’ investment and getting your money is guaranteed though at a nominal miniscule yield.

The problem is the million dollars you got back it buys one third the amount of gold it could have bought 5 years ago. That in a nutshell is the debasement of the currency at work. It is the lower standard of living at work. We’ve lived on this credit bubble for so long that he downturn is going to be very difficult to fight because we’ve become reliant on expanding credit.It’s not the right thing to do it’s just because we’ve become so reliant on it now.

Gold is so attractive in the long term because this is a trend that is intensifying. It’s a trend that’s broadening, and the tentacles are reaching throughout the world in places that it has not reached before. You’re not protected in currencies, so for me on the longer term picture gold still looks attractive even at these prices.

Michael: What do you think of the Crude Oil Market?

Greg: I think oil has been a major laggard and we haven’t liked oil until the last month or so. It’s increasingly gotten more powerful this move up in Crude Oil and its clearly breaking out this week. There’s very strong momentum including the energy stocks and the energy ETFs relative to the market as a whole.

And it’s interesting to note too that this is obviously increasingly bullish for commodities just when it look like maybe commodities have had their run and peaked. A lot of commodities have gotten to historically outrageous levels if you will with Cotton at $1.50, Copper back to $4 and Palladium pushing $800. The list of commodities that are trending in a positively has intensified this week alone. Which gets back to this whole thought process surrounding stock markets and central banks and bail outs and printing more money and balance sheets, so on and so forth.

So to me, the entire commodities complex has looked good, continues to look good, and now you can add the energies to the mix as they begin to play catch up and in fact are taking a leadership role on a short term basis. This creates all kinds of discussions we might have on what this means for inflation down the road because if you recall it was October, November, December of last year that commodities were exceptionally weak. Food like wheat and soy beans and are breaking out again this week too. Food prices could become problematic at some point going forward thanks to the monetary support for economies world wide.

Michael: One of our favorites since May of ’03 has been silver. Is silver outperforming gold?

Greg: Silver is absolutely outperforming gold. It has been a big performer and an upside leader for quite some time in the near term. I have a love for Silver as when I first started the business it was in the Silver pit in New York Cities World Trade Centerback in the hey day of $50 Silver.Talking about the bigger picture, Silver has a great appeal in that it’s a lower denomination metal, you can hold smaller quantities, exchange it for less value in terms of what you mightexchange Gold in potentially a real worst case scenario down the road. From that perspective I still like Silver. It does continue to outperform gold and I expect that to be sustained.

Michael: One of the trends you spotted was the huge surplus of gasoline inventories and when you recognized when that had reversed itself, you got bullish on gasoline. It worked out very well and I thought that was a terrific example of why analysts and institutions read what you’re doing .We’ve seen a rise in gasoline so what do you think is going on in gasoline now?

Greg: With the down turn in the economy there was less demand for gasoline ,we’re producing less and we started importing less. The next thing you know we’re drawing down inventories to meet demand. So if there is any push in the economy as a result of this monetary stimulus that will be bullish. But really it’s more a function the fact that the supply demand fundamentals have shifted. When you look at the calendar spreads, the nearby’s are commanding a price premium. I won’t say that’s abnormal but its very bullish. It indicates that there is not enough supply available for immediate delivery so the market is willing to pay a higher price for the near term contracts to try and draw that supply because it’s needed. We see a pretty dramatic shift in the gasoline markets.

I think it’s also interesting that we haven’t seen gasoline rise. When we start talking about US inflation it is certainly weighted towards energy more than food so gasoline rising will becomes problematic. If labor is not picking up, housing is not picking up, it’s only the asset markets that are inflating because of the monetary push. If gas were to rally significantly that could create a real wild card kind of problem for the Fed in terms of discreetionary spending as it will certainly put pressure on the consumer if it continues.

Michael: Always fascinating Greg, I hope you and Aileen have a wonderful Christmas season.

Dennis Gartman on Oil: “We have been stressing the changing term structure of both WTI and Brent for the past several weeks, to the point of being taken to task by many of our clients who wonder why it is that our attention is drawn so materially to this shift. Now it is clear why we have spent so much time writing about the shifting term structure. It is because the term structure changes before the flat price does and when the term structure changes those who do not change with it shall be run over by the eventual change in price. “

“Finally looking at the chart of January WTI Crude on the page previous it is obvious that it is materially over-bought in the short term and is running up against resistance as we approach $89.50. A retracement back to $84.50- $85.00/barrel would seem reasonable”

Greg is the guy who does all the work that other analysts and institutions want to have a look at. He gets behind the numbers and obviously has a terrific understanding of what’s going on. You can also subscribe to Greg Weldon’s Newsletter at: www.weldononline.com

A complimentary general admission ticket for a friend or family member (the perfect stocking stuffer)!

Anyone ordering their MoneyTalks VIP pass before December 15 will receive a 2nd ticket at absolutely no charge. Register Today HERE

Just go to www.moneytalks.net and you can just click on the World Outlook Financial Conference banner to ensure you’ve got tickets.

It was a humdinga of a weekend between our wildly successful Festivus and those pesky Raiders keeping their silver and black helmets in the hunt for a playoff spot. As I spent most of the weekend winding down and the last several hours catching up, here are some top-line vibes as we kick-off our five-session set.

A few weeks ago, I noted that the return/risk profiles that we identify for stocks, bonds and precious metals had shifted abruptly. Since then, a decline in bond prices has modestly improved expected returns in bonds, but not yet sufficiently to warrant an extension of our durations. Precious metals have become more overbought, and while we are sympathetic to the long-term thesis for gold, intermediate term risks are now elevated. Finally, we have observed a further deterioration in market conditions for stocks.

I am back from the Forbes cruise to Mexico and starting to deal with a thousand things, but first on the list is making sure you get this week’s Outside the Box. And a good one it is. In fact, it is two short pieces coming to us from friends based in London over the pond.

Both of them have to deal with the unfolding crisis that is Europe, which is going to unfold for several years as they lurch from solution to solution. The first is from Dylan Grice of Societe Generale and reminds us why we should put no stock in what leaders say about a crisis. He has lined up the statements of leaders from one crisis after another. He finds a simple, repeating pattern. And shows where we are now.

The second is from hedge fund manager Omar Sayed, who I met last time I was sin London. A very bright chap and good guy. He offers us very succinctly four paths that Europe can take. Some of them are not pretty. It all makes for a very interesting OTB. I trust your week will go well.

Your over-dosed on guacamole (and it was worth it) analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

The Three Stages of Delusion

The recent sequence of reassurances from various eurozone policymakers suggests we are in the early, not latter, stages of the euro crisis. Only an Anglo-Saxon style QE will prevent dissolution of the euro. Such a radically un-German solution will only be taken with a full acceptance of how serious the euro’s problems are. But denial persists.

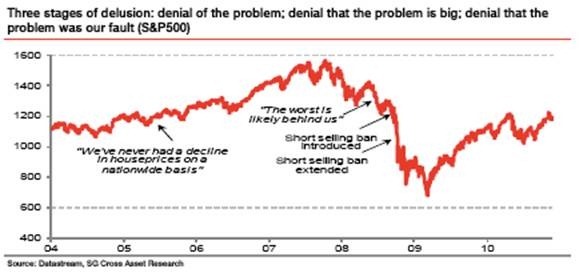

The dawning of reality hurts. Prodded and bullied along a tortuous emotional path by events unforeseen and beyond our control, we descend through three phases: the first is denial that there is a problem; the second is denial that there is a big problem; the third is denial that the problem was anything to do with us.

US policymakers’ three steps during the housing crash fit the template well. Asked in 2005 about the danger posed to the economy by the housing bubble, Bernanke responded: “I guess I don’t buy your premise. It’s a pretty unlikely possibility. We’ve never had a decline in house prices on a nationwide basis.” Here was the denial that there was a problem. But as sub-prime issues arose, Ben Bernanke reassured the world that they would be “contained.” And when Bear Stearns collapsed, Hank Paulson promised “The worst is likely to be behind us.” Here was denial that there was a big problem.

Soon the financial system was on the brink of collapse. There could no longer be any credible denial of the problem, so the locus of delusions shifted: there was a problem, but it was someone else’s fault. Thus a ban on naked short selling of financials was implemented in Sept/Oct 2008, as though the crisis was somehow short-sellers’ fault. (It certainly wasn’t the Fed’s fault, according to the Fed. Ben Bernanke argued this year “Economists … have found that only a small portion of the increase in house prices … can be attributed to the stance of US monetary policy.”)

What’s interesting is that the journey Bernanke and Co. took fits the journeys of policymakers presiding over crises past very closely, as I’ll show inside. What’s worrying is that taken in this context, eurozone policymakers’ denials/reassurances sound eerily familiar. And if these past crises are any guide, the euro crisis is still in its early stages.

A descent through the three stages of delusion characterises most crises. Dick Fuld went from saying “as long as I live, Lehman will never be sold” in December 2007, to “We have access to Fed funds; we can’t fail now” during the summer of 2008, to agreeing with a colleague that half of any capital injection then being negotiated with the Korean Development Bank be used to buy back Lehman stock, to “hurt Einhorn bad.”

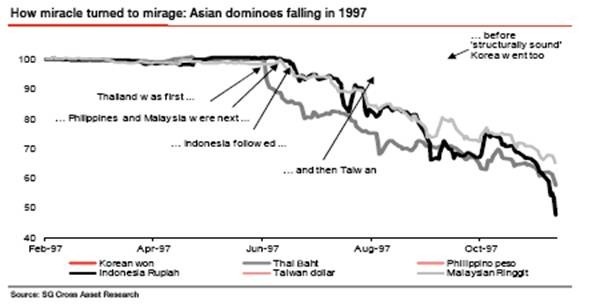

Identical stages can be traced during the Asian Crisis of 1997. For those who don’t recall, the Asian Tigers were ‘miracle’economies whose dizzying growth rates proved the superiority of export liberalisation, high investment and free markets. Their miracle image was burnished by the ‘good crisis’ they enjoyed in 1994, when their fixed exchange rate systems (they were pegged to the dollar) successfully withstood the contagion caused by the collapse of the Mexican peso.

Bear in mind that the world had bought into the Asian Tiger story hook, line, and sinker. The World Bank wrote a now infamous series of reports called “The East Asian Miracle” from 1993, lauding the strength of the region’s institutions and preaching its commitment to an export-driven growth model to anyone who’d listen. And while there was a feeling that some tigers (e.g. Thailand and the Philippines) were riskier than others (Indonesia), the idea that Taiwan or South Korea would be caught up in anything was viewed as utterly preposterous. Early in 1997, Jeffrey Sachs said:

“Since the economic structure of Korea is fundamentally different from that of Mexico, there is no possibility of recurrence of the situation that happened to Mexico.”

But early in 1997, problems emerged. The first sign of trouble came in Korea in January when a large chaebol called Hanbo Steel collapsed under $6bn of debts. Then in February, Thai property company Somprasong Land missed a payment on foreign debt in February. These turned out to be the first cockroaches. The following chart shows the sequence of events which would soon follow. First the small economies fell – then the big ones.

Yet denial that there was any problem characterized early observations. Immediately following the Thai government’s $3.9bn aid to Thai banks to cover dud property loans, Michel Camdessus – then head of the IMF – said, “I don’t see any reason for this crisis to develop further.” And on 30th June that year, Chavalit Yongchaiyudh, then Thai Prime Minister, made a televised address to the nation saying “We will never devalue the baht.”

Yet the baht was floated on 2 July. It was soon followed by the Philippine peso.

But the initial denial that there was a problem simply became denial that there was a big problem. Indonesia wasn’t Thailand, after all. According to an article in the 8th Oct 1997 New York Times:

“Indonesia’s financial condition is far better than Thailand’s was this summer … while Thailand depleted its foreign-currency reserves in a last-ditch effort to prop up its currency, the baht, Indonesia still holds foreign reserves of about $27 billion.”

And as the Indonesian crisis began to intensify and the US made financial help available as a precaution, an Administration official said: “We don’t expect that Indonesia will need to draw on our direct help, but what we need to address here is an atmosphere of contagion.”

As it turned out, Indonesia wasn’t Thailand. It was worse. It would prove to be the worst affected of the Asian tigers with a near 80% exchange rate collapse bankrupting the corporate sector which had borrowed heavily in dollars. GDP collapsed by 14%, triggering unrest and street violence which ultimately forced out President Suharto.

Yet denial that there was a big problem persisted. James Wolfensohn, then president of the World Bank, reassured that the Indonesian bailout marked the end of the crisis: “The worst is over” he proclaimed confidently.

Korea wasn’t Indonesia. Michel Camdessus, said on Nov 6th: “I don’t believe that the situation in South Korea is as alarming as the one in Indonesia a couple of weeks ago.” Yet South Korea turned out to be just as vulnerable, and certainly more costly. On December 1st 1997, the government said it had agreed to a $55bn bail-out (which then, was the largest bailout in the history of the world. In today’s money it’s a mere $75bn, less than the bill for Ireland). The storm moved on. Before petering out it would engulf Latin America, then Russia, and then the once mighty hedge fund LTCM. But for now, Asia had been destroyed. The miracle was myth. The depth of the problems was now undeniable.

Yet the denial persisted, only now it emphasised the fault of others to demonstrate that the crisis was in no way related to anything policymakers had done. It was all caused by speculators, international bankers and the foreign media. Most infamous was Malaysia’s then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed blaming George Soros, who he bizarrely implied was part of some kind of wider plot. “Today we have seen how easily foreigners deliberately bring down our economy by undermining our currency and stock exchange …” and “Soros is part of a worldwide Jewish conspiracy.”

There’s nothing unusual about the emotional need to find a scapegoat when things go wrong. As always, Shakespeare wrote about it four centuries ago. From King Lear:

“This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, when we are sick in fortune – often the surfeit of our own behaviour – we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars: as if we were villains by necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion; knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance; drunkards, liars, and adulterers, by an enforced obedience of planetary influence; and all that we are evil in, by a divine thrusting on: an admirable evasion of whoremaster man, to lay his goatish disposition to the charge of a star!”

And if we’re looking for signposts on the way to a crisis’ closing chapters, it turns out that the “excellent foppery” of blaming everyone else is a good indication. Thus, as the Greek crisis unfolded in December 2009, George Papandreou went from denial of the problem, insisting it to be “out of the question” that Greece would resort to the IMF, to denial that it was the Greeks’ fault, lamenting in March 2010 that “we ourselves were in the last few months the victims of speculators.”

As the Irish crisis reached its conclusion, Finance Minister Brian Lenihan blamed the “unintended consequences” of various German and French comments for its spiralling borrowing costs.

Today Spain is the battlefield. A few weeks ago, the Spanish were in denial that there was a problem. Zapatero said “I believe that the debt crisis affecting Spain, and the eurozone in general, has passed.” Now they are in denial that there is a big problem. Last week, Spanish Finance Minister Elena Salgado said there was “absolutely no risk” the country would need an international bailout and stressed the differences between Spain and Ireland, much as the Indonesians stressed the difference between themselves and the Thais thirteen years ago:

“Our financial sector has always had the Bank of Spain’s supervision and regulation, which is what has probably been missing in Ireland … We have a solid financial sector and we should remember that it’s the financial sector that’s provoking the difficult situation in Ireland.”

When they start blaming everyone else for their problems, we’ll know their crisis is nearly over Until then, their plight likely has some way to go.

But of course, the real issue isn’t Ireland, or Portugal or even Spain. The real crisis is the euro, and the strains continued membership is placing on the relationships between euro members and the attitude of electorates in the member states towards the single currency.

Yet policymakers are as in as much denial that there is a big problem (i.e. with the euro rather than any individual country) as Ben Bernanke and Hank Paulson were that there was a housing bust, as Dick Fuld was that Lehman was toast, or as the IMF was that Thailand, let alone Asia, had profound economic weaknesses. Last week the Finnish Central Bank head and ECB Governor Erkki Liikanen said “The euro will survive. It is not questioned.” Klaus Regling, heading up the EFSF, said “No country will give up the euro of its own will: for weaker countries that would be economic suicide, likewise for the stronger countries. And politically Europe would only have half the value without the euro.”

Such logic has been used before. Barry Eichengreen wrote in 2007 that euro membership was effectively irreversible because withdrawal would be too traumatic. But what if the cost of staying in the euro becomes so high that exit is preferable? Surely this is the risk in Germany’s current strategy.

Peripheral eurozone countries need to default. Traditionally this is done with currency debasement (which the Fed and the BoE have already begun) or by imposing a haircut on lenders. Germany refuses to sanction the former, while flagging up the latter triggered the latest bout of contagion. Instead, they are imposing depressions on countries which lose the bond market’s confidence.

How many years of austerity before the voters of Greece/Ireland/Spain/wherever blame Germany, France, or the euro for everything that is wrong with their economy? Will this become the blame game signalling the final chapter of the euro’s crisis?

I certainly hope not. Last week, Axel Weber said: “The European Financial Stability Fund should be sufficient to dissuade markets from speculating against the solvency of Eurozone member countries, and if not, more money will be provided.”

If and only if that money comes from the ECB’s printing presses – in the style of the BoE and the Fed – will Mr. Weber be correct. A large risk rally will ensue. If not, we still have a long, long way to go. On 27 May this year, following the original set-up of the EFSF, I wrote:

“The EU’s ‘shock and awe’ $1trillion rescue was certainly a big number and reflected European governments going all in. But going all in is risky if you don’t have a strong hand, and the EU’s seems weak. Two-thirds of the rescue money comes from the EU itself, which means that the distressed eurozone borrowers are to be saved by more borrowing by … er … the distressed eurozone borrowers.”

This remains the case. The EFSF is flawed. It invites speculative attack. Simply expanding it in its current form so that the ‘solvent core’ commits to raise yet more funds for the ‘insolvent periphery’ fails to address the risk that as more dominos fall the bailers shrink relative to the bailees (Italy and Spain combined – who’s spreads have been blowing out this week – are combined bigger than Germany). At what point does the insolvent periphery include so many countries that markets lose confidence in the solvency of the shrinking core to bail them out. Leaving aside for now the unpleasant reality that the solvent core might not actually be so solvent, perhaps the spread between ‘insolvent’ Greece and solvent France should be narrower? I wish I knew. In the absence of ECB printing, I suspect we’re going to find out.

John F. Mauldin

johnmauldin@investorsinsight.com

Sign up for a Free subscription for Outside the Box HERE