This month, as unleaded gasoline prices increased for 17 consecutive days (to a national average of $3.647 per gallon – up 11% thus far this year) and West Texas Intermediate crude joined Brent crude in breaking through a $100 per barrel level, energy prices emerged as a full blown political issue. While President Obama conveniently claimed that rising prices were the consequence of an improving economy (they’re not, and it isn’t) Republican fingers began to point sanctimoniously at current drilling policies. And while none of the accusers had any idea why prices were actually going up, the award for the most dangerous ‘solution’ must go to Bill O’Reilly at Fox News. The master of the “No Spin Zone” announced that high pump prices could be permanently brought down by a presidential order to restrict exports of refined gasoline. Not only does Mr. O’Reilly’s idea demonstrate contempt for the U.S. Constitution but it also displays a thorough lack of economic understanding.

Oil and gas prices are high now for a very simple reason: the U.S. Federal Reserve has gone on an unapologetic campaign to push up inflation and push down the value of the U.S. dollar. Just last week on CNBC James Bullard, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, stated this unequivocally. What is somewhat overlooked is the degree to which an inflationary policy at home creates inflation abroad. Many countries who peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar need to follow suit with the Fed. As China, for example, prints yuan to keep it from appreciating against the dollar, prices rise in China. This is especially true for commodities like crude oil.

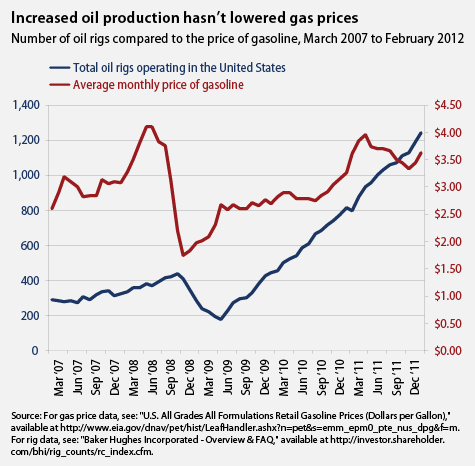

Many critics, such as Mr. O’Reilly, have relied on a limited understanding of the supply/demand dynamic to question why gas prices are currently so high at home. With domestic gasoline production at a multi-year high and domestic demand at a multi-year low, he logically expects low prices. But he fails to grasp the fact that the price of gasoline is set internationally and that U.S. factors are only a component.

O’Reilly’s loudly proclaimed solution is to limit the ability of U.S. refiners (and drillers) to export production abroad. If the energy stays at home, he argues, the increased supply would push down prices. Although O’Reilly professes to be a believer in free markets he argues that oil (and gasoline by extension) is really a natural resource that doesn’t belong to the energy companies, but to the “folks” on Main Street. What good would “drill baby drill” do for us, he argues, if all the production is simply shipped to China?

First off, the U.S. government has no authority whatsoever to determine to whom a company may or may not sell. This concept should be absolutely clear to anyone with at least a casual allegiance to free markets. In particular, the U.S. Constitution makes it explicit that export duties are prohibited. Furthermore, energy extracted from the ground, and produced by a private enterprise, is no more a public good than a chest of drawers that has been manufactured from a tree that grows on U.S soil. Frankly, this point from Mr. O’Reilly comes straight out of the Marxist handbook and in many ways mirrors the sentiments that have been championed by the Occupy Wall Street movement. When such ideas come from the supposed “right,” we should be very concerned.

But apart from the Constitutional and ideological concerns, the idea simply makes no economic sense.

In 2011 the United States ran a trade deficit of $558 billion. For now at least America has been able to reap huge benefits from the willingness of foreign producers to export to the U.S. without equal amounts of imports. China supplies us with low priced consumer goods and Saudi Arabia sells us vast quantities of oil. In return they take U.S. IOUs. Without their largesse, domestic prices for consumers would be much higher. How long they will continue to extend credit is anybody’s guess, but shutting off the spigots of one of our most valuable exports won’t help.

In recent years petroleum has become an increasingly large component of U.S. exports, partially filling the void left by our manufacturing output. According to the IMF, the U.S. exported $10.3 billion of oil products in 2001. By 2011, this figure had jumped nearly seven fold to more than $70 billion. How would our trading partners respond if we decided to deny them our gasoline?

Keeping more gasoline at home could hold down prices temporarily, but how much better off would the “folks” be if all the prices of Chinese made goods at Wal-Mart suddenly went up, or if such products completely disappeared from our shelves because the Chinese government decided to ban exports that they declared “belonged to the Chinese people?” What would happen to the price of energy here if Saudi Arabia made a similar decision with respect to their oil?

But most importantly, limiting the ability of U.S. energy companies to export abroad will do absolutely nothing to improve the American economy. As a result of our diminished purchasing power, American demand for oil has declined in relation to the growing demand abroad. Consequently, we are buying a continually lower percentage of the world’s energy output. Consumers in emerging markets can now afford to buy some of the production that used to be snapped up by Americans. If U.S. suppliers were limited to domestic customers, then prices could drop temporarily. But what would happen then?

With the U.S. adopting a protectionist stance, and with gasoline prices in the U.S. lower than in other parts of the world, less overseas crude would be sent to American refineries. At the same time lower prices at home would constrict profits for domestic suppliers who would then scale back production (and lay off workers). The resulting decrease in supply would send prices right back up, potentially higher than before. The only change would be that we would have hamstrung one of our few viable industrial sectors. (For more about how diminishing supplies could exert upward pressures on a variety of energy products, please see the article in the latest edition of my Global Investor newsletter).

Mr. O’Reilly can spin this any way he wants it, but he is dead wrong on this point. It is surprising to me that such comments have not sparked greater outrage from the usual mainstream defenders of the free market. To an extent that very few appreciate, America derives a great deal of benefits from the current globalization of trade. Sparking a trade war now would severely reduce our already falling living standards. And given our weak position with respect to our trading partners, such a provocation may be the ultimate example of bringing a knife to a gun fight.

Rather than bashing oil companies, O’Reilly, as well as other frustrated American motorists, should direct their anger at Washington. That is because higher gasoline prices are really a Federal tax in disguise. The government’s enormous deficit is financed largely by bonds that are sold to the Federal Reserve, which pays for them with newly printed money. Those excess dollars are sent abroad where they help to bid oil prices higher.

For years, mainstream economists argued that as long as unemployment remained high, the Fed could print as much money as it wanted without worrying about inflation. The argument was that the reduction in demand that results from unemployment would limit the ability of business to raise prices. However, what those economists overlooked was the simultaneous reduction in domestic supply that results from a weaker dollar (the consequence of printing money).

I have long argued that neither recession nor high unemployment would protect us from inflation. If demand falls, but supply falls faster, prices will rise. That is exactly what is happening with gas. The same dynamic is already evident in the airline industry. Fewer people are flying, but prices keep rising because airlines have responded to declining demand by reducing capacity. Since seats are disappearing faster than passengers, airlines can raise prices. At some point Americans will be complaining about soaring food prices as much more of what American farmers produce ends up on Chinese dinner tables. Because the Fed is likely to continue monetizing huge budget deficits, Americans are going to be consuming a lot less of everything, and paying a lot more for those few things they can still afford.

For full access to the March 2012 edition of the Global Investor Newsletter, click here