Somehow in the last few months I found myself going from merely concerned about developed-world markets to outright advocating defensive positions. I thought some of the presentations at my Strategic Investment Conference would cheer me up. They did not.

In fact, what I heard from economists, portfolio strategists, analysts, and hedge fund managers made me even more bearish. Yes, this conference by its nature tends to dwell on risks. The people I invite are successful precisely because they know how to spot (and avoid) macroeconomic risks.

This year’s crowd was generally gloomy (with some notable and vigorous exceptions), though I didn’t sense any panic. It was more frustration at the lack of clarity and choices, coupled with general concern that there is a major central bank policy error brewing. One of my associates captured the mood with this tweet on the second day.

https://twitter.com/PatrickW/status/735582566762336256

(We had several excellent sponsors, but I didn’t think to invite any antidepressant companies. We may do that next year.)

Now, you could take a contrarian view and say that “bad” is actually bullish. You might even be right – but I don’t think so. Bullish/bearish isn’t a binary state. There are alwaysshades of gray. You can be bullish on some assets and bearish on others. You can think the stock market is generally overpriced but still see value in certain stocks. You can be positive on some countries and negative on others.

In fact, most speakers had at least one if not several investment classes they were quite bullish on rather than US stocks. Mark Yusko asked the three ETF portfolio construction panelists to name their favorite country ETF. I was actually surprised when all three answered with the same country – India. There were several very positive comments on Mexico and the business climate and opportunities there. There was even a mention (by former Dallas Fed president Richard Fisher) of how efficient their regulators and bureaucracies were. Not something we hear about the US or Europe.

I think we are often pessimistic because we want easy answers. We want to either buy stocks or sell them and then do something else. Successful investing isn’t so simple. You have to observe, analyze, and consider the alternatives before you come up with the right solutions.

Sometimes you can go through that process and still end up bearish on almost everything. Richard Fisher seems to be in that camp. Asked in our final wrap-up panel Friday morning how his own portfolio was positioned, Fisher answered with one word: “Fetal.” And while his answer got a general laugh and a lot of pushback on the final panel from Niall Ferguson, who thinks he sees the beginning of an inflection point, it seemed a pretty good summary of the conference. I think most people walked away trying to think how they could position their portfolios more defensively.

My own suggestion was to diversify among trading strategies rather than among long-only asset classes, a theme that we will explore in a future letter.

You don’t often hear such candor from people like Fisher. He’s been in the banking system’s top tier for a long time and is hardly a permabear. He earned his reputation as a monetary hawk because he thought the economy was strong enough to handle higher interest rates.

Fisher also has a good bubble-spotting record. I discussed one of his speeches in a 2006 letter I called “Honey, I Created a Bubble.” Even then, he talked about the housing market entering a correction. We only later learned how painful a bubble’s bursting could be.

More recently, Fisher earned headlines last January when he claimed that the Fed had “front-loaded a tremendous market rally” in 2009. Here is a three-minute video you should watch.

Fisher’s SIC comments were broadly consistent with what you hear in the video. He thinks the markets will take a long time to digest the Fed-driven bubble, and in the meantime he is very cautious. Markets are fragile, and any kind of shock could get ugly. I believe that is what he meant by the “fetal” comment.

We will get into what those shocks might possibly be in a moment, but this seems to be a good time to bring up today’s job report. It indicated a shockingly disappointing 38,000 new jobs, with a downward revision of 59,000 jobs to the two prior month’s reports.

Some 458,000 people left the job market, which is what pushed the unemployment rate down to 4.7%. The 3-month average is now just 116,000 versus the 6-month average of 170,000 and the 12-month average of ~200,000.

The Federal Reserve had been making noises as though they might finally raise rates at the June meeting or at the July meeting at latest. It is very hard for me now to imagine them doing so. We’re watching the unfolding one of the greatest policy errors in central banking history. Not having taken the opportunity to raise rates during 2014 when new jobs were averaging 250,000, the Fed may now have waited too long, such that any rate increase, no matter how trivial, becomes a shock.

This was actually one of the main points of my own speech, that during the next global recession we’re going to see the most massive combined policy errors by central banks ever witnessed. All will not end well.

If somehow (in a world turned upside down) a President Donald Trump asked me for my recommendation as to a new Federal Reserve chairman, Richard Fisher would be on my very short list. I’m not certain he is masochistic enough to want to do it, but he is patriotic enough that he might step once more into the breach for the good of the country. (My suggestion would be the same to a President Hillary Clinton, but I would bet that the European Central Bank’s raising rates next month into positive territory is lots more likely than my ever being approached by a Democratic president on economic policy.)

What might the shocks be that Richard Fisher was alluding to? Anatole Kaletsky of Gavekal listed three global economic risk factors in his SIC remarks. Annoyingly, all three are political. I say “annoyingly” because I’m old enough to remember when governments did not pretend to control the world economy. Now governments everywhere are bigger and more ambitious, as are central banks. They still can’t control the economy, but leaders think they can, and their attempts usually make things worse.

You can watch the short video above, but in summary Anatole’s potential trouble spots are

- The June 23 “Brexit” vote in the UK

- US elections on November 7

- German elections in mid-2017.

Any one of these has the potential to spark major economic disruption. Richard Fisher said most people underestimate Brexit’s consequences. Departing from the European Union would force the UK to renegotiate hundreds of treaty agreements on everything from airport landing rights to bank settlements. Currently the UK is one of the developed world’s strongest economies. A win by the “leave” side could stop that trend, even if Brexit ultimately works out for the best.

I have friends on both sides of Brexit, by the way; and as an American I don’t get to vote. Nor does Richard Fisher. I will respect whatever decision the UK voters make. Their house, their rules. Regardless, their choice will affect the whole world. Just as many international readers are unsettled by the concept of a Donald Trump presidency, my English readers should understand the concerns of those who look upon the Brexit vote in much the same way. Brexit will bring changes to the system, if it happens, and we’re not sure how those changes will affect us and whether they will be good.

The same is true, possibly more so, if American voters send Donald Trump to the White House. Whatever you think about Hillary Clinton (and I will admit I don’t think much), she is at least a known quantity. Nothing she does is likely to rattle the markets. Trump, should he win, will bring an entirely new way for Washington to operate (and that is not necessarily bad). His trade, immigration, tax, and foreign policies could be quite unlike what anyone alive today has seen before.

David Rosenberg, for his part, thinks Trump will be good for the economy but bad for Wall Street. Watch this:

While we’re talking about Trump, you might also like these clips from George Friedman and Pippa Malmgren.

Eurasian Headache

George Friedman was as geopolitically negative as some of the other speakers were on the economy. He thinks the Eurasian landmass, home to most of the human race, is falling apart. The European “Union” is a troubled relationship at best and could soon see an ugly breakup. Russia is struggling to find balance in a post-Soviet, post-oil world. China has to make a tough transition away from its export boom years and build a sustainable domestic economy. And Middle East problems continue to foment.

The German problem Anatole Kaletsky listed as a key risk is on Friedman’s radar screen, too. Friedman believes Germany is far too dependent on exports that are now dwindling as its customers tighten their belts – and that is before we enter a global recession. The situation might be manageable if other challenges weren’t also demanding attention.

- Merkel may have successfully papered over the Greek debt problem, but she won’t be so lucky with much larger Italy. The banking system there is completely unsustainable. (George and I have shared notes and discussions on this topic. The picture in Italy is much more serious than the mainstream media is portraying).

- The refugee crisis is going to get worse before it gets better, and frictions will likely strengthen Germany’s right-wing and nativist political parties. Presently they are no threat to Merkel’s leadership but could well become so after 2017 elections.

- A renewed NATO Cold War against Russia is forcing Germany to increase defense spending and devote more attention to foreign policy at the precise time it really needs to get its home situation straight.

- As pessimistic as George was on Eurasia, he was almost equally positive on the New World. He thinks the Canada/US/Mexico trade zone is the world’s economic center of gravity. No one else has the same combination of domestic demand, technology, innovation, innovation, and political stability. Yes, we have problems, not least of which is the massive debt we accrued in the course of reaching this dominant position. Other than Brazil (and the distressingly sad case of Venezuela), however, the Americas are in far better shape than Europe, Asia, or Africa.

After the first day’s generally negative talks by analysts and economists, everyone was ready for a real-world view. How did someone who actually manages real money see the situation? We had several panels and speakers on that topic. Let’s focus on one – my good friend Mark Yusko, who heads Morgan Creek Capital Management. He manages billions and pioneered the endowment approach many universities now take with their portfolios. Surely, you might think, someone in his position would have a more enlightened view than those bearish economists.

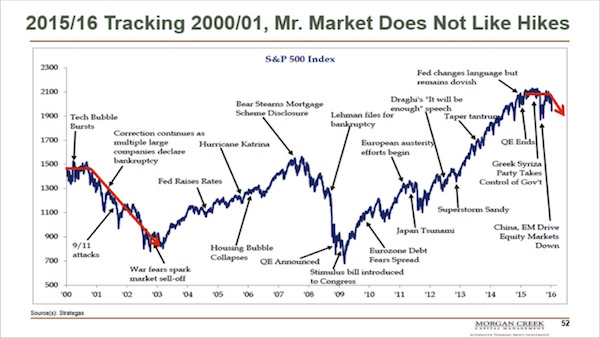

Enlightened, yes, but hardly bullish. Mark poured cold water on whatever bullishly warm feelings the audience may have clung to. He listed not one but ten plausible scenarios that could send markets down to the basement. I will focus on his “Surprise #6: Déjà vu, Welcome to #2000.2.0.”

That’s right: Mark says it’s year 2000 all over again. That was when the tech bubble popped and sparked an ugly bear market and recession.

This theme resonated for me because this very newsletter actually grew out of my late-1990s updates on the Y2K problem. In a sea of pundits forecasting either doomsday or no problems at all, I was firmly in the middle and believed that the combination of economic imbalances (including the tech bubble) and computer glitches would land us in a recession. All my research told me we would see some problems and disruptions but not the collapse of civilization. That call turned out to be right. Even more amazingly, the portfolios I suggested in my book at the time, The Y2K Recession, turned out to be right on target. I don’t think I have ever been as lucky with my prognostications since that time.

Among the disruptions, however, was the Federal Reserve’s move to withdraw the liquidity it had pumped into the system for those who expected a payment system breakdown and thus hoarded physical cash. Alan Greenspan took the fed funds rate from 5.4% on Y2K day to 6.5% in October 2000.

(Younger readers will do a double-take on those numbers. Yes, borrowing overnight money once cost more than 6%. Furthermore, the Fed is perfectly capable of hiking rates 100 basis points or more in less than a year. Or at least it used to be.)

The bear market that followed was, at the time, the most significant anyone had seen since the early 1980s. High-flying tech stocks crashed, one after the other; and Bill Clinton’s move to release Human Genome Project data sent the biotechnology sector up in flames. It was a painful time that no one who lived through it wishes to repeat – but Mark Yusko thinks we will repeat it, starting now. Here’s one of the 100 or so slides from his presentation.

In the 2000–2003 period we had the tech bubble bursting, corporate scandals like Enron, the 9/11 attacks, and an honest-to-God, old-fashioned, job-killing recession. I remember at the time how everyone kept thinking, “Ok, this has been bad, but it’s over now.” But it wasn’t over. After repeated fake-outs and final capitulation, we finally emerged from the muck (just in time to start an unsustainable housing bubble, but that’s another story). It was at the end of that recession that I coined the term Muddle-Through Economy.

One thing people forget is that we had a very accommodative Fed during that time. As I said above, Greenspan pushed short rates up to 6.5% in September 2000. Just a year later, he had them down to 3% and ultimately to 1% in mid-2003. That Fed was willing to move at light speed if it thought it necessary, unlike more recent regimes.

Another eerie parallel Mark noted was in corporate earnings. Observe the red dashed line in this chart.

The shaded areas are the last two recessions. We see that earnings peaked a few quarters ahead of each recessionary period, then slid deeply into negative territory before recovering as the recession ended.

This time around we seem to be about halfway down to the trough. It’s entirely possible we are in a recession right now and don’t know it yet. The start date is discernible only in hindsight.

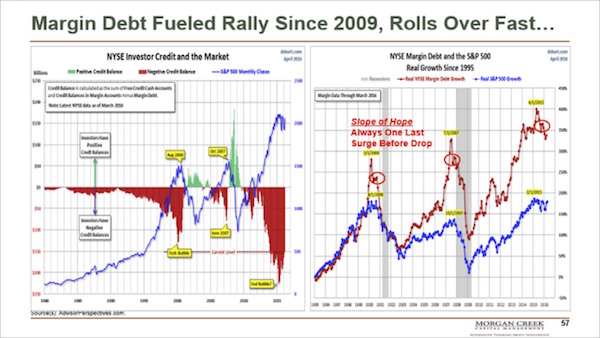

Margin debt is another bad sign. The red area in the left chart below shows how debit balances build up right along with market peaks.

Again, right now we appear to be in a place much like the early stages of the last two bear markets.

Finally, 2016 also marks the eighth year of the presidential cycle. The average stock return for the eighth year of all US presidential terms since 1901 is -14%. So if you liked 2000 and 2008, you should love the way 2016 ends (gulp). (By the way, I admit that there are not many data points to actually determine whether there is anything to the eighth year of the presidential cycle. The chart might just be data mining to make your bearish argument look good. Then again…)

So where in all this do we find any hope? Mark explained in his voluminous quarterly outlook (read it here, and please note that you have to get to page 27 before you actually begin the analysis. The first part is a comparison of Prince and Shakespeare to the markets. Fun reading, though…)

In the equity markets, gains most often happen slowly and losses usually happen quickly. You can see this in the numbers, as the average bull market is much longer than the average bear market (more than five times longer at 97 months versus 18 months). Therefore, it is critical to always be looking for long opportunities, especially during the brief corrective periods (when things go on sale). To reiterate a point we have discussed in prior letters which was a paraphrase of the line from The Merry Wives of Windsor, “The essential problem that we highlighted last quarter is that when it comes to bubbles and crises, you can be a few hours early, but you can’t be one minute late.”

To use another old quote, the time to buy is when blood is running in the streets. If, like Mark Yusko, you are already in defensive positions (or in Richard Fisher’s fetal position), you will soon have some excellent buying opportunities. Those with less foresight are going to dump some valuable assets, not because they want to but because they have no choice. They’ll need the liquidity.

What should you buy? That’s not entirely clear yet, nor will we be able to catch the precise bottom. As they say, no one will ring a bell. But if Mark Yusko is right, the chance ought to arrive in the next year or so.

I could go on for another hundred pages sharing the new information we heard at SIC. I think you have a lot to chew on, though, plus some videos to watch and re-watch, so I’ll leave it there. More next week.

A funny thing about the fetal position: babies eventually find their way out of the darkness and into the real world. They encounter pain and tears on the journey but are always glad they made it.

We who go through the coming economic rebirth will likewise feel some pain. Yet the pain will have a purpose. It will end in due course, and we’ll have a new world to enjoy.

John Mauldin

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com

Given the correction Rambus Chartology has an excellent take on Gold Stocks: Be Prepared