Is this time different? I’ve often characterized our approach to the financial markets as a value-conscious, historically-informed, evidence-driven discipline. In recent years, we’ve often been asked whether the world has changed in a way that makes historical evidence an inadequate guide to investing.

Our own narrative in the half-cycle since 2009 certainly invites that question. While a good part of that was a self-inflicted outcome related to my fiduciary stress-testing inclinations in 2009, and we’ve adapted far more than is likely to be obvious until the present market cycle is complete (see Setting the Record Straight to understand those challenges and how we’ve addressed them), the broader question remains – do historical regularities no longer apply?

In Probably Approximately Correct, Leslie Valiant describes the conditions required by both living organisms and artificial intelligence “ecorithms” in order to learn and successfully use induction from observations drawn from the environment. In order to reliably learn from inference, two assumptions are required.

First, we can’t expect those lessons or generalizations to be useful in contexts that are fundamentally different from the environment that produced the observations used for learning. In other words, lessons learned in one world may be poor guides in a far different world. This, of course, has been the perennial argument of speculators during every bubble in history. But we should be careful about over-using that argument. The “invariance assumption” doesn’t require that the world cannot change – it only requires that there are some regularities that remain true. Second, some useful criterion or regularity must in fact be detectable. That is, there must be some “learnable regularity” that can actually be inferred from the evidence – a random world with no relationships between cause and effect is not an environment that will produce useful or predictive generalizations.

In some cases, those learnable regularities can be derived on the basis of clear theoretical relationships that describe how the world works with reasonable accuracy.

For example, every long-term security is fundamentally a claim on a very long-duration stream of cash flows that can be expected to be delivered into the hands of investors over time. For a given stream of expected cash flows and a given current price, we can quickly estimate the long-term rate of return that the security can be expected to achieve (assuming the cash flows are delivered as expected). Likewise, for a given stream of expected cash flows and a “required” long-term rate of return, we can calculate the current price that would be consistent with that long-term rate of return. The failure to understand the inverse relationship between current prices and future returns is why investors frequently argue that rich equity valuations are “justified” by low interest rates, without understanding that they are really saying that dismal future equity returns are perfectly acceptable.

We also observe the very regular tendency for profit margins to increase during economic expansions (presently corporate profits are close to 11% of GDP), and to contract during softer periods. Corporate profits as a share of GDP have always retreated to less than 5.5% in every economic cycle on record, even in recent decades. Since stocks are most reliably priced on the basis of long-term cash flows, and not simply Wall Street’s estimate of next year’s earnings, we find that valuation measures that are either relatively insensitive to profit margin swings, or that correct for their variation over the economic cycle, are much better correlated with actual subsequent market returns than measures such as price/forward operating earnings that don’t do so.

Our valuation concerns don’t rely on any requirement for earnings or profit margins to turn down in the near term. Valuation is a long-term proposition that links the price being paid today to a stream of cash flows that, for the S&P 500, have an effective duration of about 50 years. In evaluating whether “this time is different,” it should be understood that current valuations are “justified” only if 1) the wide historical cyclicality of profits over the economic cycle has been eliminated, 2) the average level of profit margins over the next five decadeswill be permanently elevated at nearly twice the historical norm, 3) the strong historical advantage of smoothed or margin-adjusted valuation measures over single-year price/earnings measures has vanished, and 4) zero interest rate policies will persist not just for 3 or 4 more years, but for decades while economic growth proceeds at historically normal rates nonetheless. Believe all of that if you wish. Without permanent changes in the way the world works, on valuation measures that are best correlated with actual subsequent market returns, stocks are wickedly overvalued here.

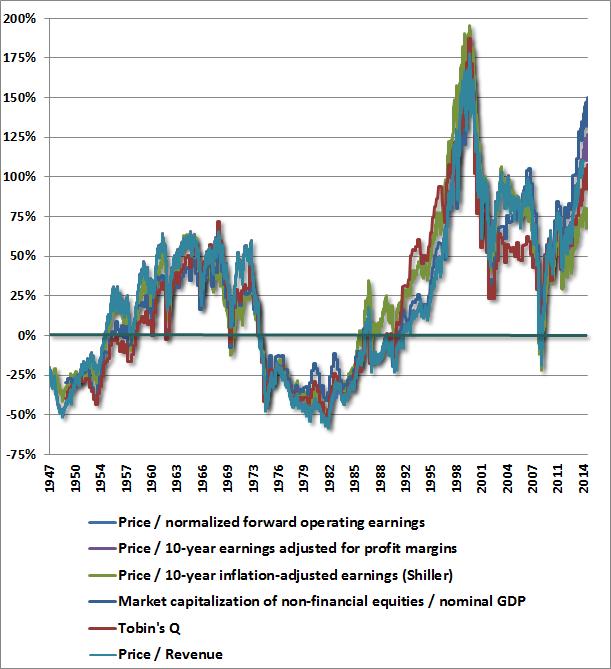

The charts below show several of the measures that have the strongest relationship (correlation near 90%) with actual subsequent 10-year S&P 500 total returns, reflecting data from the Federal Reserve, Standard & Poors, Robert Shiller, and valuation models that we have published over the years. The first chart shows these measures as the percentage deviation from their historical norms prior to the late-1990’s equity bubble. While it’s easy to lose sight of the extremity of the present situation, these measures are well over 100% above their respective norms, on average. On the most reliable measures, we estimate that S&P 500 valuations are now only about 15-20% short of the 2000 extreme, and are clearly above every other extreme in history including 1901, 1929, 1937, 1972, 1987, and 2007. Again, these measures are also better correlated with actual subsequent market returns than popular alternatives such as price/forward operating earnings and the Fed Model (which adjusts the S&P 500 forward operating earnings yield by the level of 10-year Treasury yields).

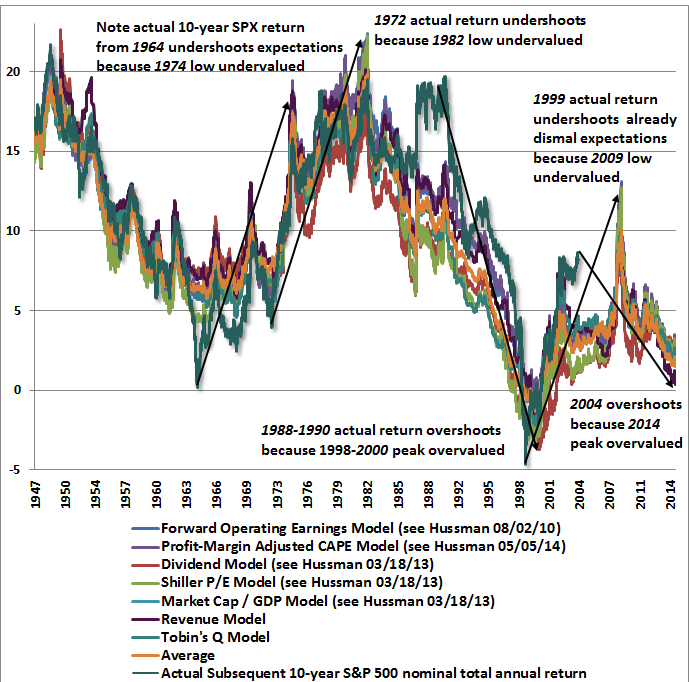

As of last week, based on a variety of methods, we estimate likely S&P 500 10-year nominal total returns averaging just 1.5% annually over the coming decade, with negative expected returns on every horizon shorter than about 8 years. The chart below shows the historical record of these estimates (in percent) versus actual subsequent 10-year S&P 500 total returns. What’s notable is not only the strong correlation between estimated returns and actual subsequent returns, but also that the errors are informative.

For example, notice that the actual 10-year S&P 500 total return in the decade following 1964 was significantly lower than one would have projected at the time. The reason is that the 1974 market plunge was so brutal, with the market losing half of its value, and bringing the new estimate of prospective returns to significantly above-average levels. Looking at this chart at the 1974 low, one might have been concerned that the methods were too optimistic since the prior 10-year return was so much worse than what one would have projected a decade earlier. Those concerns would have been unfounded, as the 1974 low represented one of the best secular buying opportunities in history, especially for the broad market.

Conversely, the actual 10-year S&P 500 total return in the decade following 1988-1990 was significantly higher than one would have projected at the time. The reason is that the 2000 market bubble was so extreme, bringing the new estimate of 10-year S&P 500 returns to negative levels. Looking at this chart at the 2000 peak, Wall Street would have undoubtedly argued that these measures of valuation had become unreliable or useless. That argument would have proved tragically wrong, as the S&P 500 promptly lost half of its value (three-quarters of its value for the Nasdaq), and posted negative total returns for well over a decade.

Given the full weight of the evidence, it should be clear that one can’t just say “well, look, the S&P 500 has done better than these models would have projected a decade ago,” and use that as a compelling argument that this time is different and historical regularities no longer hold. Quite the opposite – the overshoot in S&P 500 total returns since 2004 – relative to the prospective returns one would have estimated at the time – is highly informative that stocks are strenuously overvalued at present. That conclusion has strong statistical support. In fact, when we examine the historical evidence, we find that there’s a -68% correlation between the error in the projected return over the past decade and the actual subsequent total return of the S&P 500 in the following decade. That is, the more actual 10-year S&P 500 returns exceeded the return that was projected, the worse the S&P 500 generally did over the next10 years. Notably, the “Fed Model” has a correlation of less than 48% with actual subsequent 10-year returns. It’s sad when a valuation measure that is so popular is outperformed even by the errors of better measures.

Of course, there are also environments where either clear theoretical relationships don’t exist, or aren’t adequately recognized or understood, and people have to learn through a process of trial, error, and experience. That brings us to quantitative easing and zero-interest rate policy. Here, we have a mixture of clear relationships that aren’t adequately understood, as well as relationships that are largely psychological and can’t be derived mathematically.

On the subject of clear relationships, we know precisely how to quantify the impact that zero interest rate policy should have on valuations. Suppose, for example, that historically normal equity market valuations have generally been associated with Treasury bill yields averaging about 4%. Now suppose that Treasury bill yields are expected to be held at zero for the next 3-4 years. It follows (and this can be demonstrated with straightforward discounting arithmetic) that this expectation would “justify” stock valuations about 12-16% above their historical norms. That elevated valuation would adjust for the reduction in short-term interest rates by commensurately reducing the prospective future return on stocks by that same 4% increment for the next 3-4 years. The problem is that if this relationship isn’t recognized or understood, it becomes easy to casually argue “well, lower interest rates justify higher stock prices” without any concern that stocks are actually more than double reliable historical norms already.

Which leaves us with the effect of quantitative easing on the psychology of investors. It’s here where recent years have been particularly challenging for evidence-based, historically-informed analysis. Over the short run, market returns are driven by mindset, but ultimately, they are driven by valuation. As Benjamin Graham famously remarked, “in the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

In the current cycle, central banks have stuffed the ballot box. That doesn’t make long-term prospects any better, but it has induced substantial yield-seeking speculation for several years running. In past market cycles across history, once the market established certain extreme conditions (which we’ve regularly described as “overvalued, overbought, and overbullish”), stocks typically retreated in relatively short order. In the half-cycle since 2009, that regularity appeared to largely vanish, and stocks have advanced even in the face of conditions that would normally have triggered a plunge. Again, this isn’t because higher valuations were justified by zero-interest rate policy, but rather because the policy has triggered persistent yield-seeking speculation despite valuations that offend empirically reasonable assumptions.

Fortunately, there’s a practical approach to adapt to situations when individuals behave in a way that ignores analytical relationships, and in situations where those relationships can’t be quantified directly. As Leslie Valiant correctly observes, for some classes of learning methods, “one can automatically translate a weak learning algorithm into a strong learning algorithm. The idea is to use the weak learning method several times to get a succession of hypotheses, each one refocused on the examples that the previous ones found difficult and misclassified.” In recent years, the difficult and misclassified conditions have primarily been those where overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions were present, and yet the market was advancing in a way that was inconsistent with history. On that front, we’ve been faced with a good example of “this time” being “different.”

Notice that the strategy isn’t to abandon disciplined analysis or to discard every lesson of history. When one finds an aspect of the environment that legitimately appears “different,” the proper response is to embrace disciplined analysis even more strongly – focusing on misclassified instances and determining why they are misclassified. We know that the market often ignores monetary actions – the Fed was aggressively easing throughout the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 plunges – so appeals to Fed easing aren’t enough. Since we’re analytically-driven investors and not data-miners, our efforts have been somewhat different than the “boosting” algorithm that Valiant describes, but the principle is much the same. In practice, we asked “historically, what has distinguished overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions that were followed by air-pockets, free-falls, and crashes from similar conditions that had few negative consequences?” The answer? Generally speaking, the negative outcomes were coupled with either widening credit spreads or deteriorating market internals (what we’ve sometimes called “trend uniformity”). In the absence of such measures of increasing risk-aversion, those overextended syndromes have been much less hostile, on average. As it happens, implementing that “overlay” not only reduces the extent of misclassifications in the half-cycle since 2009, it also reduces misclassified defensiveness during other bubble periods such as the runup to the 2000 and 2007 market peaks.

What does all of this mean for the market at present? Since the initial “air-pocket” in stocks a few weeks ago, I’ve been careful to emphasize that I’ve had no opinion regarding near-term direction, and that we could observe either a corrective short-squeeze or a fresh market plunge. There was quite simply very little evidence that supported any directional view besides the expectation of continued volatility. Last week, however, the market re-established conditions extreme enough to place the present instance among what I’ve often called the “who’s who of awful times to invest.” Importantly, and in contrast to a few similarly extreme conditions we’ve seen in recent years, we presently observe both widening credit spreads and – at least for now – deteriorating internals and unfavorable trend uniformity on our measures of market action.

It’s certainly possible that credit spreads will narrow and market internals will improve. In that case, it won’t make the market any cheaper, but my impression is that it would mitigate the immediacy of our concerns. Longer-term, we would still anticipate dismal returns on a 7-10 year horizon, but an improvement in credit spreads and market internals would essentially be a signal that investors had shifted back to a more risk-seeking psychology at least for a bit.

In short, our views will shift as the evidence shifts, but here and now, the market has re-established overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions that mirror some of the most precarious points in the historical record such as 1929, 1937, 1974, 1987, 2000 and 2007. That syndrome is now coupled with continued evidence of a subtle shift toward more risk-averse investor psychology, primarily reflected by internal dispersion and widening credit spreads. I’ve often emphasized that the worst market outcomes have historically been associated with compressed risk premiums coupled with a shift toward risk aversion among investors. In those environments, risk premiums typically don’t normalize gradually – they do so in abrupt spikes. We’ll continue to respond as the evidence changes, but under current conditions, we view the investment environment for stocks as being among a handful of the most hostile points in history.

The foregoing comments represent the general investment analysis and economic views of the Advisor, and are provided solely for the purpose of information, instruction and discourse. Please see periodic remarks on the Fund Notes and Commentary page for discussion relating specifically to the Hussman Funds and the investment positions of the Funds.

—

Prospectuses for the Hussman Strategic Growth Fund, the Hussman Strategic Total Return Fund, the Hussman Strategic International Fund, and the Hussman Strategic Dividend Value Fund, as well as Fund reports and other information, are available by clicking “The Funds” menu button from any page of this website.

Estimates of prospective return and risk for equities, bonds, and other financial markets are forward-looking statements based the analysis and reasonable beliefs of Hussman Strategic Advisors. They are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of the prospective returns of any of the Hussman Funds. Actual returns may differ substantially from the estimates provided. Estimates of prospective long-term returns for the S&P 500 reflect our standard valuation methodology, focusing on the relationship between current market prices and earnings, dividends and other fundamentals, adjusted for variability over the economic cycle (see for example Investment, Speculation, Valuation, and Tinker Bell, The Likely Range of Market Returns in the Coming Decade and Valuing the S&P 500 Using Forward Operating Earnings ).