Michael Lewitt is one of the most provocative writers I know. He consistently gives me something to chew on with his monthly letter. How he comes up with all those quotes (usually from sources I have never read but should have) amazes me. He has a unique view of the markets as he run Collateralized Debt Obligation funds and really understand the nitty-gritty of the bond and credit markets.

His work is subscription only, but he has graciously allowed me to use his latest piece as this week’s Outside the Box. For those interested in subscribing, you can go to his website at www.hcmmarketletter.com.

And if you haven’t already voted in the US, then do so. I am somewhat of a political junkie. My normal election night routine is stay up watching the various news channels, “Tivoing” what I am not watching so I can skip the commercials and watch at least three channels. Sadly, I will be getting on a plane Tuesday late afternoon to London so will not know what happens until I get to my hotel. Some quick news feed and then onto the office of Variant Perception where my co-author Jonathan Tepper and I will bury ourselves for four days finishing the book.

Your hoping the Rangers can pull it out analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

Keynesian Confusion

“At the present moment people are unusually expectant of a more fundamental diagnosis; more particularly eager to receive it; eager to try it out, if it should be even plausible. But apart from this contemporary mood, the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the word is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slave of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

John Maynard Keynes (1936)

Ironically, John Maynard Keynes himself remains by far the most influential of the defunct economists from whom the madmen in authority are distilling their frenzy today. Economists occupy a world in which their theoretical musings have enormous real world consequences. Unlike their colleagues in the hard sciences, however, economists do not have the luxury of testing out their theories before inflicting them on the rest of us. The Keynesian experiment being run by governments and central banks over the past two years is a case in point.

Keynesian policies are inflicting untold damage on the U.S. and global economies today. Things did not have to be this way; Keynes did not have to be misread. His antidote for slow economic growth and high unemployment – massive doses of government spending – was appropriate in midst of the 2007-8 financial crisis, just as it was sensible during the 1930s global depression that Keynes was experiencing while he was writing The General Theory. In end of world scenarios, government spending is the last resort. But once the economy stabilizes – even at a diminished rate of growth – Keynesian medicine will cripple the patient if it is not withdrawn and replaced with a healthy fiscal regimen. Unfortunately, policymakers – in particular the current and past Chairmen of the Federal Reserve – have shown themselves to be either unwilling or incapable of making the transition from crisis management to post-crisis management of monetary policy. As a result, today’s Federal Reserve is missing the second great lesson of Keynes’ work, the “paradox of thrift.”

The most extended discussion of the paradox of thrift occurs in Chapter 23 of The General Theory, which is actually part of a series of chapters contained in Book IV entitled “Short Notes Suggested by the General Theory.” The discussion of the paradox of thrift in this chapter is primarily devoted to a historical survey of the idea and is relatively disjointed. Keynes’ clearest description of the concept comes much earlier in The General Theory when he writes the following:

“The reconciliation of the identity between saving and investment with the apparent ‘free-will’ of the individual to save what he chooses irrespective of what he or others may be investing, essentially depends on saving being, like spending, a two-sided affair. For although the amount of his own saving is unlikely to have any significant influence on his own income, the reactions of the amount of his consumption on the incomes of others makes it impossible for all individuals simultaneously to save any given sums. Every such attempt to save more by reducing consumption will so affect incomes that the attempt necessarily defeats itself. It is, of course, just as impossible for the community as a whole to save less than the amount of current investment, since the attempt to do so will necessarily raise incomes to a level at which the sums which individuals choose to save add up to a figure exactly equal to the amount of investment.”

In order for the fallacy of thrift to slow economic growth, the capital that consumers and businesses are saving would normally have to be available to recirculate in the economy through loans or investments. This recirculation is precisely what is not happening today, or at least not nearly at the rate necessary to lift growth to a level that would create significant job growth. And this is the Keynesian lesson that fiscal and monetary policymakers appear to have forgotten as they have forged their post-crisis strategy – rather than indiscriminately easing monetary conditions, it is necessary to create an environment in which savings-conscious consumers and corporations are willing to allow their funds to recirculate.

The reason that the current recovery is below par is that the economy is experiencing a massive paradox of thrift. A combination of factors has led individual economic actors – both consumers and corporations – to believe that it is in their best individual interest to save rather to spend, to repay debt rather than borrow. The result has been an increase in the personal savings rate from slightly negative to approximately 6-7 percent, and a significant improvement in corporate balance sheets (corporations are now sitting on approximately $1 trillion of cash). This has improved the financial condition of these individual economic actors, but deprived the broader economy of consumption and investment spending.

Unwise economic policy choices have led to the current situation. Consumers are saving instead of spending because the value of their homes has declined significantly, which is a result of the pro-cyclical monetary policy and lack of regulation that contributed to the housing debacle. Businesses are limiting their hiring and expansion plans due to the increasing regulatory burden being placed on them by the government, by fears of impending tax increases, and by the general anti-business tone coming out of Washington D.C. Investors are fleeing the stock market because regulators don’t have the guts to stand up to Wall Street and address dangerous practices such as the repeal of the uptick rule, naked CDS on systemically important institutions (which allows speculators to mount bear raids on companies such as BP plc), and flash and algorithmic trading. The combination of all of these policy failures has led to a massive crisis of confidence in the American model of capitalism, which has become as badly corrupted as the Japanese model that is responsible for Japan’s decades of deflation and economic paralysis. And our current politics offers little prospect for change.

This is the landscape investors are facing as we enter one of the most important weeks in American politics and markets in a long time. HCM is devoting so much time to a discussion of policy and politics because these are the forces that are driving financial markets today. The performance of individual companies is far less important than macroeconomic factors in determining investment performance. The United States is on the verge of two important events that will affect not only its own immediate future but the future of the global economy: the November 2 mid-term elections, and the November 3 meeting of the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee. The mid-term elections are expected to produce a significant shift in power in the U.S. Congress, with Republicans expected to regain control of the House of Representatives, move into an unassailable blocking position in the Senate, and make major gains at the state level as well. The financial markets have been treating these two early November dates as early Christmas presents, but the post-holiday hangover may be brutal. Financial markets should be careful what they wish for on November 2 and 3. Despite likely short-term market gains, they may ultimately be staring at coal in their stockings.

The Mid-Term Elections

The mid-term elections promise a big victory for the Republicans, a party whose brand was so severely devalued a mere two years ago that the media was already writing about President Obama’s second term agenda. But a Republican resurrection is hardly likely to improve economic or social conditions; the Republicans’ rigid anti-tax, anti-regulatory agenda has inflicted great damage on this country. The repudiation of Congress that will occur on November 3 should be considered bi-partisan – both parties have been abject failures. The political process has become deeply corrupted and dysfunctional. Returning the party to power that presided over 8 years of budget profligacy and regulatory malpractice between 2000 and 2008 is hardly a great accomplishment; it merely promises to temper the worst anti-business and anti-growth policies of the Obama administration and its Congressional minions. Many believe that political gridlock will ensue, although we would not be surprised to see progress made on several policy fronts such as a compromise on taxes and perhaps some marginal budget cuts (not entitlement reform unfortunately). Those promoting a Republican victory argue that at least things won’t get worse for the economy if the Obama agenda is stopped in its tracks, but the economy will get worse if America’s ill-advised fiscal and tax policies remain in place.

After the election, HCM expects a dangerous outbreak of populism that will most likely take the form of protectionist economic measures primarily aimed at China. If this occurs, it will not be good for the financial markets. There are already rising pressures in Congress to take action against China, and we will have to see if these sentiments will fade after the election. Our expectation is that they will not. The demagogic danger is a real one and it is growing. With more than one in eight Americans on food stamps, new revelations about mortgage foreclosure abuses, and the appearance on the scene of politicians of the ilk of New York gubernatorial candidate Carl Paladino, Delaware Senatorial candidate Christine O’Donnell, and Ohio Congressional candidate Rich Lott, who used to spend his spare time engaging in Nazi reenactments (with his son!) and was actually endorsed by future House Speaker John Boehner, it is a small leap to protectionist legislation aimed at China and other countries that can be scapegoated for America’s own failures. The way to combat China’s currency policy is not through punitive measures but through policies that improve America’s competitive economic position, a concept that is unlikely to gain currency in today’s devalued marketplace of ideas. Instead, bad ideas are likely to gain ascendancy and provide political cover for American politicians trying to avoid making the tough choices needed to right the American economy. We may not need our politicians to be nuclear scientists, but this country isn’t going to served by electing outright idiots either.

QE2

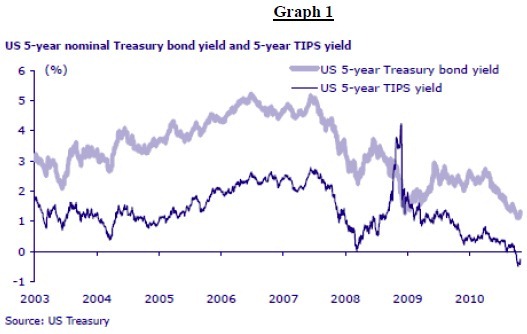

One day after the mid-term elections, the Open Market Committee is expected to announce the details of its plan to engage in a second round of quantitative easing (QE2) pursuant to which the central bank will intervene directly in the financial markets to purchase as much as US$1 trillion of Treasury securities. The stated purpose of QE2 is to prevent inflation from dropping below the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 percent, which is somehow supposed to stimulate economic growth. This ignores the fact that record low interest rates over the past two years have failed to do precisely that. Nonetheless, all of the Fed’s jawboning about its plans has had a significant impact on the financial markets. The Dow Jones Industrial Average is up about 12% since Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke began hinting that further quantitative easing was coming two months ago. Inflation expectations have shifted sharply upward, with a recent 5-year TIPs auction resulting in a negative real yield of -0.55 percent (see Graph 1 below). On the other hand, the yield on 10-year and 30-year Treasuries has increased by about 30 and 40 basis points, respectively, since the Fed announced its intentions. Markets are heeding the history lesson that monetary policy plays a key role in shaping post-crisis economies; the problem thus far is that the markets aren’t doing what the Fed wants them to do. If the Fed does not play small ball with QE2, however, we would expect rates to drop back down in the near term. We doubt, however, that reducing already low rates is going to stimulate much of anything other than more frustration on the part of savers.

HCM has a hard time making a case that inflation is either a serious or imminent threat despite the signals coming from the market. Hedge fund star John Paulson recently told investors that he believes that inflation will rise to the double-digits by 2012, a forecast we find excessive in degree and timing although not ultimately in direction (calling for higher inflation in the future is an easy call; the tough call is deciding when inflation will hit). There is still too much excess capacity in too many areas of the economy – finance, real estate, housing – to create significant near-term inflationary pressures. The type of inflation Mr. Paulson is predicting really speaks to a different type of scenario that would involve a collapse of the U.S. dollar and with it the U.S. economy, which would be consistent with reports that Mr. Paulson holds 80 percent of his considerable personal assets in gold. HCM is a strong believer in gold and even a stronger believer in a dollar collapse and continuing U.S. economic weakness barring a 180 degree change in policy, but we don’t see it happening as quickly as Mr. Paulson.

Opinion among the Fed governors concerning the wisdom and prospects for quantitative easing is hardly uniform. For example, during an October 19 speech before the New York Association for Business Economics, Richard W. Fisher, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas admitted that “[i]n my darkest moments, I have begun to wonder if the monetary accommodation we have already engineered might even be working in the wrong places.” St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank President James Hoenig has been a consistent dissenter from recent Fed decisions and in HCM’s opinion is the lone voice of reason in a sea of Keynesian insanity. Despite these doubts, the central bank is intent on mounting another feckless attack on the powerful deleveraging trends at work in the post-crisis world.

In a twist that must have amused the Fed’s harshest critics, it was reported that the Fed surveyed government bond dealers and investors about their expectations of the initial size of any new program of debt purchases and the time period over which it would be completed. It also asked firms how often they expected the program to be reevaluated by the Fed and to estimate its ultimate size. Coming less than a week before the Open Market Committee, this request is consistent with the tradition of the Fed cow-towing to the financial markets. Former Chairman Alan Greenspan used to rely on the wisdom of the stock market, and declared to the world that it was a “conundrum” when interest rates did not respond to Fed policy moves in accordance with his ideology. Ben Bernanke’s Fed doesn’t even wait for the markets to opine – it asks the markets in advance about their expectations, presumably so the central bank will not disappoint them and see them drop (God forbid!). That’s one way to avoid conundrums, but it is no way to manage monetary policy. The markets are counting on a $1 trillion program of quantitative easing over a reasonably short period of time; anything less could cause a sell-off in equities. The markets, as usual, are only focusing on the short-term and ignoring the long-term risks created by ill-advised monetary policies. QE2 may sustain the markets for a brief period of time, but sooner rather than later the markets are going to have to pay the piper for the mountains of debt and extended period of artificially low interest rates that this policy has promulgated.

As I have written in El Mundo and spoken about at the recent Value Investing Congress in New York, QE2 is not only unlikely to work but is certain to contribute to future financial instability. The financial system is already sitting on US$1 trillion of excess reserves. The reason that these reserves are not being used to grow the economy through capital spending or to create jobs is not that interest rates are too high. Rather, reserves are going unutilized because of a profound lack of confidence on the part of economic actors bred by anti-growth policies promoted by the Obama administration (particularly healthcare reform) and the threat of significantly higher taxes (as much as US$6 trillion over the next 10 years if current plans aren’t altered. ) QE2 will do nothing to address these factors suppressing demand for funds. QE2 is a monetary policy tool being used to address a problem that has nothing to do with monetary policy. As such, it is misguided and is unlikely to work. What it will do, however, is further swell the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and lower the value of the dollar, neither of which will contribute to the long-term strength of the American or global economy.

But QE2 doesn’t only fail to aim at the right target (employment); it doesn’t really aim at anything at all. Instead, QE2 basically sprays money indiscriminately into the economy instead of targeting money at productive activities. Current fiscal and tax policy promotes peculation at the expense of productive growth; examples include the lax rules governing derivatives trading and leveraged buyouts, activities that add nothing to the productive capacity of the economy. Without fiscal and tax policy changes designed to promote productive growth, the excess reserves created by QE2 will end up in the hands of speculators in the financial industry. This will increase systemic leverage and exacerbate existing overcapacity in unproductive areas such as finance and real estate. QE2 without fiscal and tax policy changes is simply a continuation of the boom-and-bust regime that has dominated global financial markets for the past three decades.

The Stock of the Fed is Dropping Quickly

The once Teflon reputation of the Federal Reserve has taken a beating since the financial crisis, but its management of the post-crisis environment has lifted criticism of the central bank to a new and perhaps unprecedented level. Previously, the most strident attacks came from the likes of Congressman Ron Paul and other libertarians; today they are coming from respected market figures such as Morgan Stanley economist Stephen Roach, PIMCO’s Bill Gross, and Jeremy Grantham.

Readers of this publication are well aware that HCM has long admired the work of Morgan Stanley’s Stephen Roach. Mr. Roach is one of the more intellectually honest and outspoken central bank critics on the scene today. On October 12, he addressed the World Knowledge Forum in Seoul, South Korea and delivered one of the harshest public critiques of the Federal Reserve that has been made in many years. The primary thesis of the speech was that policy makers have failed to learn from the policy errors made by Japan. He writes that “it is now debatable as to whether there was ever a clear understanding of the true Lessons of Japan and what they might imply for macro policy management in the modern world.” This is important because “[i]n the aftermath of the Crisis of 2009-09 – and the Great Recession it spawned – a legacy of post-crisis debt and deleveraging is now increasingly global in scope.” The correct lesson of what has happened to Japan over the past two decades is not that Japanese authorities moved with insufficient speed and aggression to deal with credit and asset bubbles. The correct lesson is that such bubbles must be identified earlier and avoided in the first place.

Mr. Roach rightly criticized the Federal Reserve for failing to spot obvious bubbles in advance (the Internet Bubble, Housing Bubble, and Corporate Bond Bubble are three obvious examples). But even worse, he said, is that the Federal Reserve Chairman was leading the intellectual charge supporting the case that these were not bubbles.

“One of the most disturbing features about each of these episodes is that the Chairman of the Federal Reserve – steeped in his ideological convictions that markets always know best – led the charge in denying that they were bubbles. He argued that the NASDAQ bubble was well supported by the productivity renaissance of the New Economy. Housing bubbles could only be local – never national. And the unprecedented tightening of credit spreads was an outgrowth of stunning advances in financial innovation.”

As someone who was fortunate enough to warn in this publication (and elsewhere) of each of these bubbles in advance, HCM welcomes Mr. Roach’s willingness to speak out about the failure of so-called leading economists to miss such obvious imbalances. These imbalances are what cause the types of market crashes that wipe out years of investment performance in the blink of an eye, or create the opportunity to profit from selling short. Moreover, these bubbles are not that difficult to identify if one is willing to look at the facts with an objective eye and not be corrupted by the madness of crowds. As I wrote in The Death of Capital:

“there are clear indicia of when asset prices are rising at unsustainable levels….Any significant departure from long-term valuation trends should capture the concern and attention of central bankers and trigger a response. But the types of deviations from the norm that occurred in the decade preceding the crisis of 2008 were far more than mere departures from long-term trends; they were obvious bubbles that required no special economic knowledge to identify. Stock prices traded at a multiple of 351x earnings on the NASDAQ Stock Exchange at their peak on March 10, 2000; the average price/earnings multiple at previous market peaks had been no higher than 20 before that. The risk premium (known as spread) on Credit Suisse’s High Yield Index reached 271 basis points over Treasuries on May 31, 2007, a record level that exceeded the historical average of 570 to 580 basis points by over 50 percent.”

Unfortunately, we are again heading into dangerous territory as a result of the Federal Reserve’s ill-advised zero interest rate policy, which is being exacerbated by an irrational fear of disinflation that is leading to its truly hare-brained scheme to engage in QE2. You can be sure we will do our best (as we have in the past) to sound the warning when markets get out of hand again. It is only a matter of when, not if, this occurs.

Mr. Roach also criticizes the Federal Reserve for failing to take into account the fact that financial bubbles have a devastating effect on the real economy. “A key lesson from Japan,” he said, “is for the authorities to be especially mindful of the lethal interplay between asset and credit bubbles and related distortions in the real economy. That lesson was totally lost on the Federal Reserve over the past decade.” In the post-crisis environment, monetary policy is being guided by deflation fears fed by Japan’s experience that lead to policies that are likely to exacerbate those very same deflationary risks. Mr. Roach warns: “[t]hat could very well be the single greatest flaw of a narrow and mechanistic inflation-targeting policy rule – a framework that does not allow for the unintended consequences of low nominal interest rates in spurring a steady string of asset and credit bubbles that could well compound deflationary risks over time.” In other words, the Fed’s narrow mandate (or its narrow interpretation of its mandate) is leading it to adopt policies that are exacerbating the very risks it is seeking to mitigate.

Mr. Roach’s solution is to add to the central bank’s mandate a requirement to maintain “financial stability.” Such a requirement would provide monetary authorities “with the political cover to attack asset and credit bubbles before they had dangerously destabilizing impacts on markets and wealth- and credit-dependent economies.” He believes such a change is necessary because we have had “a Federal Reserve that was swayed more by ideology than discipline, and debased by politically-motivated fiscal authorities who have become fixated on short-term stimulus while ignoring longer-term considerations. In this environment, we can no longer count on the promises of policy makers to act in accordance with the lessons they have learned from Japan or from the Great Crisis of 2008-09.” HCM would slightly modify Mr. Roach’s last statement. Policymakers have simply failed to learn the right lessons from the 2008-09 crisis. As we argued above, rather than learning from Keynes that a debt crisis should be solved with more debt, the authorities should have better understood how the paradox of thrift would operate in a post-crisis environment and developed policies to deal with that phenomenon.

Bill Gross was also harshly critical of Federal Reserve policy in his most recent Investment Outlook. In so many words, he accused the U.S. government of running a massive Ponzi scheme, although he softened this comment by noting that public debt always has Ponzilike characteristics. But the Ponzi scheme currently being run by the U.S. government is unprecedented in size and scope. Mr. Gross argued that:

“with growth in doubt, it seems that the Fed has taken Charles Ponzi one step further. Instead of simply paying for maturing debt with receipts from financial sector creditors – banks, insurance companies, surplus reserve nations and investment managers, to name the most significant – the Fed has joined the party itself. Rather than orchestrating the game from on high, it has jumped into the pond with the other swimmers. One and one-half trillion in checks were written in 2009, and trillions more lie ahead. The Fed, in effect, is telling the markets not to worry about our fiscal deficits, it will be the buyer of first and perhaps last resort. There is no need – as with Charles Ponzi – to find an increasing amount of future gullible, they will just write the checks themselves. I ask you: Has there ever been a Ponzi scheme so brazen?”

PIMCO is a huge holder of Treasury and other types of securities that are likely to benefit in the short run from QE2, but Mr. Gross correctly frets about the inevitable inflationary consequences of this policy. Inflation, of course, could decimate PIMCO’s long bond positions when it begins to rear its ugly head (although we assume he is hedged), so Mr. Gross is not only making a principled argument but also to some degree talking his book (which is his right).

Jeremy Grantham, in a Quarterly Letter entitled “Night of the Living Fed,” makes the compelling argument that debt doesn’t correlate with long-term growth rates. Debt, he writes, “is the paper world. It is, in an important sense, not the real world.” He continues:

“In the real world, growth depends on real factors: the quality and quantity of education, worth ethic, population profile, the quality and quantity of existing plant and equipment, business organization, the quality of public leadership (especially from the Fed in the U.S.), and the quality (not quantity) of existing regulations and the degree of enforcement. If you really want to worry about growth, you should be concerned about sliding education standards and an aging population. All of the real power of debt is negative: it can gum up the works in a liquidity/solvency crisis and freeze the economy for quite a while.”

Mr. Grantham has long been a critic of Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve, but he could hardly contain himself in his last quarterly letter. He provides a great deal of fodder for the growing intellectual case against the pro-cyclical path that monetary policy has taken under its two most recent Chairmen.

Market Recommendations

We still expect the stock and bond markets to maintain their strength through the end of the year, particularly in the aftermath of a Republican victory in the mid-term elections and the announcement of QE2. Our short-term oriented readers should act accordingly. The corporate credit markets are paying absolutely no attention to company quality; anything with a decent coupon is trading up. The risk trade is clearly on.

Readers with a long-term focus should continue to accumulate gold and limit their investments in the credit area to bank loans (through mutual funds), BB/BBB corporate bonds, and stocks that have lower-than-market p/e ratios and pay dividends. We would avoid Treasuries at all costs. Lending to our government at 2.6 percent for 10 years is a great way to become a millionaire – if you’re already a billionaire. Sooner or later, everything being earned on the upside of this liquidity-induced rally will be given back in spades – the only question is when.

Michael E. Lewitt

mlewitt@harchcapital.com

John F. Mauldin

johnmauldin@investorsinsight.com